In 1988 Alturas, Florida, a middle-aged mother came down with startling symptoms. The cause of her death – and the alleged circumstances behind the killing – astonished investigators.

◊

When it comes to murder investigations, the simplest explanation is typically the correct one (think Occam’s razor). It’s become a true crime cliché: Isn’t it always the husband? Although disproportionate numbers of murdered women are, in fact, killed by their romantic and domestic partners, sometimes there’s a wild card at play. Some cases are so inexplicable, the true culprit so outside investigators’ initial purview, that they seem worthy of their own Hollywood film adaptations. Or, in the strange and tragic case of Peggy Carr, lifted straight out of an Agatha Christie novel.

The Victim

It was the fall of 1988, and 41-year-old Peggy Carr was having doubts about her whirlwind marriage to Parealyn “Pye” Carr. Their early passion had cooled and tensions were high, particularly after Peggy discovered Pye’s infidelity. But the matter was complicated: Peggy and Pye had a blended family with children from previous marriages, as well as a grandchild. For their sake, Peggy was determined to make the marriage to Pye work.

Things took a dour turn on October 23 when, on a waitressing shift, Peggy began to experience peculiar symptoms – chest pain, trouble breathing, and intense burning in her limbs. Pye, away on a hunting trip, returned home to find Peggy nearly incapacitated; he took her to the hospital.

Doctors initially had no explanations for her condition, with one doctor even suggesting that her symptoms were psychosomatic. Peggy got better during her stay at the hospital, but after going home, they started up again. Not only that, but two of the boys, Travis and Dwayne, both fell ill with the same symptoms, necessitating they all return to the hospital.

At this point, Peggy had developed a new symptom: Her hair was falling out. Neurologist Richard Hostler had observed something similar in a patient during his residency. He determined that Peggy was being poisoned, and tests confirmed his suspicions; Peggy’s results showed the presence of thallium poisoning, a chemical element traditionally used as a rodenticide and insecticide. The thallium toxicity level in Peggy’s system was 20,000 times any typical level found in the human body. Travis, Dwayne, and Pye also tested positive, albeit at much lower levels.

Peggy remained at the hospital for four months, deteriorating to the point where she could no longer speak. Having been raised with deaf parents, however, she was able to communicate in sign language to her sister, Shirley. Before she slipped into a coma, her family members later reported, she repeatedly signed the word “Why?”

Doctors were able to save the children, but not Peggy; the levels of the poison in her body were simply too high. On March 3, 1989, Peggy was taken off life support, and investigators set out to answer her final, desperate cry for answers.

The Investigation

Police searched the Carr residence extensively for what might have been tainted in the household. They tested the well water and even fruit from the family’s orange grove, eventually zeroing in on empty Coca-Cola bottles in the home. They tested these bottles as well as unopened ones from the same pack and found the bottles were positive for thallium. They questioned Pye and the children; none of them remembered where the Coca-Cola had come from.

(Credit: Nathan Stein, via Pexels)

In the late ’80s, concerns over product tampering were high. It had been just a few years since the Tylenol Murders, a case in which an unknown culprit terrorized Chicago by tampering with bottles of Tylenol, replacing the contents of capsules with cyanide. Because of these concerns, the police called in the FBI.

In addition to the thallium in the Coca-Cola bottles, there were tiny tool marks on the caps, indicating that someone had removed them, tainted the bottles, and then resealed them. Judging by the concerted effort involved in the tampering, the FBI determined that the bottles hadn’t been tainted at the time of their production or in a store. Instead, they theorized, the poisoning was done by someone Peggy knew.

Pye was the natural suspect. Beyond the troubled marriage, police also learned that Pye worked at a local mine, where he would have access to a chemical like thallium. However, police were skeptical that he would have chosen to poison himself and his children, and he was eventually cleared.

As the investigation pivoted from Pye, he brought to light two new clues. He informed police that, in July of that year, he had received a menacing typewritten letter. The note, which was addressed to “Pie Carr,” read, “You and all your so-called family have two weeks to move out of Florida forever or else you all die. This is no joke.” The family hadn’t taken the note seriously at the time.

Pye also mentioned to police that their relationship with their next-door neighbors, Dr. Diana Carr (no relation) and her husband George Trepal, had not always been rosy. Diana and George frequently complained about loud music and other sounds coming from the bustling Carr household. George also reported his neighbors to the zoning board for converting their garage into living quarters.

Still, could these minor territorial disputes have led to murder? Police interviewed Diana and George, which did little to assuage their growing suspicions. George appeared nervous during the interaction, insisting he knew nothing about what happened to Peggy. But when police asked him who he thought might want to harm the Carrs, his response was revealing. “Someone must have wanted them to move out of the neighborhood,” George said.

The Genius

George Trepal was born in 1948 to a New York City police officer and an elementary school teacher. From early on, George was different, his intelligence level far exceeding that of his peers. He went on to study chemistry and psychology at Clemson University in South Carolina. While a student, he dabbled in drugs and showed signs of paranoia. He also developed a fondness for drugging other people without their consent, once covering the doorknob of his dormitory with hallucinogens as payback to students he believed were breaking in. Trepal’s drug use soon evolved into manufacturing. He was arrested in 1975 for operating a methamphetamine lab and sentenced to three years in prison. Suspiciously, the method George used to cook his meth requires the use of thallium.

(Credit: Felix Mittermeier, via Pexels)

After serving his time, he began a career as a computer programmer and sought out individuals who shared his level of intelligence. This pursuit led him to Mensa, a society exclusively available to individuals who score in the 98th percentile of formalized IQ tests. Through Mensa circles, he met Diana, an accomplished orthopedic surgeon, and they married in 1981. In addition to their IQ levels, George and Diana had something else in common: They were both interested in true crime and murder mysteries. The pair even began organizing “Murder Mystery Weekends” for their local Mensa chapter, an opportunity for members to shmooze, dress up, and potentially solve a pretend murder.

The Detective

Police remained suspicious of Trepal, but they needed concrete evidence. They hatched a plan, bringing in seasoned investigator Detective Susan Goreck for a sting operation. They eventually coined the operation “Pale Horse,” after the 1952 Agatha Christie novel, in which a murderer utilizes thallium poisoning to dispatch victims while blaming the murders on black magic.

Using the name “Sherry Guin,” Goreck set out to insinuate herself into George and Diana’s lives. What better environment to do so than a Mensa Murder Mystery Weekend? Using her pseudonym, Susan Goreck signed up for the event, to be held at the Winter Haven Holiday Inn on April 14, 1989.

George clearly reveled in playing the role of murder maestro. But the line between truth and fiction became blurred when, just weeks after Peggy’s death, George distributed a booklet to Murder Mystery Weekend participants, intended to set the stage for the theatrical proceedings. It read, “When a death threat appears on the doorstep, prudent people throw out all their food and watch what they eat. Hardly anyone dies from magic. Most items on the doorstep are just a neighbor’s way of saying, ‘I don’t like you. Move or else.’”

Can a sophisticated computer analysis of every word Agatha Christie published reveal a deeper level to her writing? Watch this provocative MagellanTV documentary to find out!

During a weekend of masquerade, Goreck became friendly enough with George to share details from her own (fabricated) life. She told him she was recently divorced from a lawyer (earlier, she’d overheard him make a salty joke about lawyers). She wanted to establish herself as someone who had struggled, who was intelligent, and who shared George’s interest in true crime and mystery. Knowing that George and Diane’s house was for sale, she also told George that she needed a new place to live.

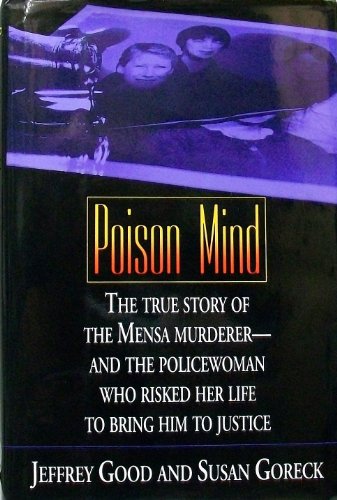

After the festive weekend, they invited her to visit the house, which betrayed the nature of its eccentric tenants. As Goreck describes in Poisoned Mind, a book she co-wrote with Jeffrey Good about the case, a junk room contained buckets of minerals, rocks, and gemstones. A library overflowed with botany and chemistry books flanked by dinosaur collectibles; elsewhere, a shelf housed a collection of Agatha Christie novels. Goreck engaged with George, allowing him to prattle on about his interests. But Goreck wanted unfettered access to the house.

As she waited for an answer about buying or renting the home, she continued pursuing a friendship with George. Diana, busy with her medical practice, seemed unperturbed. The pair picnicked together and visited the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg. All the while, Goreck shared stories from her fictional abusive marriage to a controlling narcissist. At one point, George wryly suggested she poison her ex to get rid of the problem – but he never confessed to murder.

Cover of Susan Goreck and Jeffrey Good’s Poison Mind (Source: Publishers Weekly)

“Once I got to know him, I found him very funny and witty,” Goreck would later reflect. “But what also came out was how he backed away from people he had a problem with. That fits the profile of the poisoner perfectly … someone who is going to do something underhanded because it’s non-confrontational.”

Finally, Diana and George decided to move to Sebring, Florida, where Diana was setting up a new practice. They agreed to let Goreck rent. (At this point, the Carr family had relocated.) Upon George and Diana’s departure, crime scene technicians swept in, where they discovered chemicals, a bottle capping machine, and a bottle containing white residue. Tests confirmed it was thallium.

Police had what they needed to arrest George. They found him in his new Sebring residence, standing on the stairs wearing only underwear. Although Diana was outraged at the police’s intrusion, George casually asked, “Can I put some clothes on?”

Additional evidence included a pamphlet written by Trepal called “Chemistry for the Complete Idiot, Practical Guide to Chemistry,” and a “General Poison Guide” containing pages copied from other sources; several featured a detailed discussion of thallium. And, in both of Trepal’s residences, police found concealed rooms containing beds and bondage equipment, which George insisted were simply photography darkrooms and props for Murder Weekends.

The Trial

In January of 1991, George Trepal was charged on 15 counts of attempted and first-degree murder, poisoning, and product tampering. George’s defense team pointed to the circumstantial nature of the evidence. Couldn’t Diana just as easily have tainted the Coke bottles? The defense’s claims failed to convince the jury, however, and they returned a guilty verdict for the man who, in the words of prosecutor John Aguero, “thought he was so smart he could literally get away with murder.”

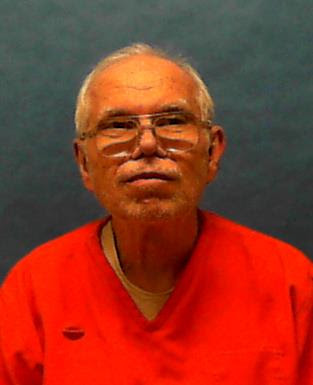

George Trepal sits on death row. (Source: Commission on Capital Cases)

Trepal’s attorneys filed petitions with the court, though, arguing that some testimony had been inaccurate and that evidence related to the possible guilt of Pye Carr was kept from the defense. Despite lingering questions, these filings were deemed insufficient to warrant a new trial.

Trepal remains on death row in Raiford, Florida. Diana, the murder mystery enthusiast and fellow Mensa member, divorced him in 1996. In 2011, one of Trepal’s friends from Mensa, Stewart Prince, shared his thoughts about Trepal’s prison days.

"He's still trying to keep a good mind,” he said. “He does lament that there are very few people on his wing who are anywhere near his level of education or intellect."

It’s a rather somber end to a case seemingly plucked from the pages of fiction. But Peggy Carr is no character in a cozy mystery. And, unlike in a meticulously plotted novel, there’s no definitive answer to the very question the victim so urgently posed on her deathbed.

Ω

Matia Madrona Query is a freelance writer and the editor of BookLife, the indie author wing of Publishers Weekly.

Title Image credit: Davide Baraldi, via Pexels