Editor's Note: The caption for a photograph of participants in a 1964 civil rights march in Mississippi misidentified one of the protesters as Bob Moses. The identity of that person is unknown. The caption has been corrected.

The summer of 1964 was a turning point in the history of the United States and the struggle for civil rights. Among other significant events, many white Americans had their consciences awakened by acts of racist violence and lawlessness in the Deep South, especially in the state of Mississippi. Three men were killed there in a terrorist attack by members of the Ku Klux Klan – cold-blooded murders that became symbolic of the price paid as African Americans sought to exercise their rights during Mississippi’s hard-fought Freedom Summer.

◊

Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price had those three young men in his sights all day. He and his racist cohort kept the activists under stealthy surveillance as the men drove into Philadelphia, Mississippi, the morning of June 21, 1964. When Price received word that the trio had been spotted at the ruins of a church that had been burned down earlier that month, that was all the cause he needed to kick off a long-standing plan the team had devised to eliminate the outsiders.

Price was out searching near the burned church for the men’s blue Ford Fairlane, a car well-known to him, when he noticed it in his rear-view mirror. He turned his patrol car around and made a beeline to pull them over. Before the three men could make it out of Philadelphia, Price used his authority as an officer of the law in Neshoba County (where the city was located) to arrest them and take them to jail – for “speeding.”

Chaney, Goodman, Schwerner: Captives of a Corrupt Legal System

Once at the station, the three activists were held for questioning about the destruction of the church they had just visited. Meanwhile, the deputy sheriff’s co-conspirators were preparing for the men’s final disposition. Price, while operating under color of law, was also in the Ku Klux Klan. And as the three men – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner – waited, resigned to pay the speeding fine and eager to get out of town, a crew comprising KKK members was out in the woods digging graves with a Caterpillar land excavator.

Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price’s cover story to delay the men, that the three were suspected in the burning of the church, was shockingly cynical. Witnesses to the conflagration knew that the people involved were representative of the KKK/law enforcement power structure in the area. Even if not a participant himself, Price certainly knew who was behind the crime.

_Freedom_Summer_papers._(9068632240).jpg)

Freedom Summer activists work to organize Mississippians to register to vote, 1964. (Source: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, via Wikimedia)

Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner paid the fine and were released. After that, they were never heard from again. Price had them followed to a remote area on a road that led out of the county, and he chased them down again. Each man was shot at point-blank range, their bodies buried in graves beneath an earthen dam. The young men’s car was burned to a shell and abandoned in the woods. It took six weeks, plus the belated intervention of the FBI and a call from an anonymous source, to find their bodies.

Civil Rights Activists Run into Racist Threats – And Violence

Why did James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner pose such a threat in the eyes of the Neshoba County KKK? The Klan, whose influence in much of the country had diminished since its heyday in the 1920s, was still quite active in the South. It recognized what the three civil rights activists represented to the Mississippi status quo. As the vanguard of a growing civil rights movement, these men threatened the longstanding power structure of the Deep South: white citizens benefiting from rights and privilege denied to often terrorized, oppressed African Americans.

For decades, the movement for equal rights had been met with lethal violence. Force and intimidation were standard tactics in the suppression of Black people who dared to seek full rights as American citizens and to resist discrimination in the Jim Crow South. During the 1950s, coordinated protests using nonviolent methods led to some successes, such as when Rosa Parks sparked a successful citywide boycott of the segregated public transportation system of Montgomery, Alabama. However, national media coverage of atrocities perpetrated against people of color in the South – and elsewhere – was spotty.

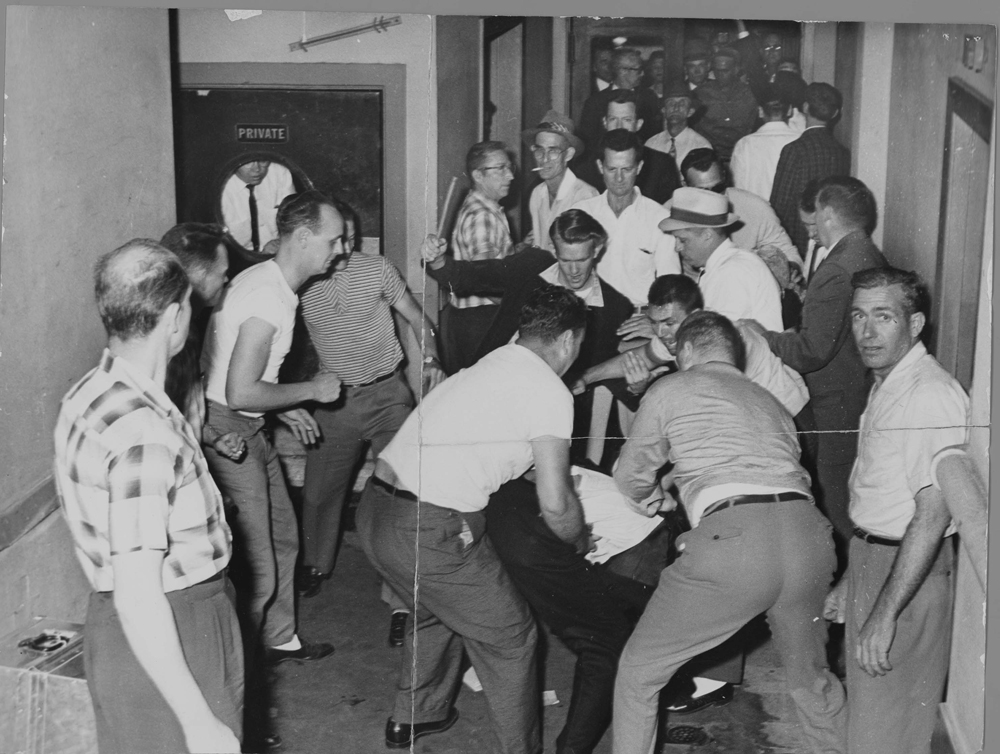

In 1961, coordinators of civil rights activities across the South came to the realization that, to achieve their goals, they needed to reach sympathetic citizens throughout the nation with news of their protests. To this end, a civil rights advocacy group, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), recruited hundreds of young people of all ethnicities to participate in what were called Freedom Rides: integrated groups of newly minted, trained activists traveling on buses from the North to demonstrate the unfairness of racial discrimination.

A mob composed of White men beats Freedom Riders in Birmingham, Alabama, 1961. (Source: National Endowment for the Humanities, via Wikimedia)

Freedom Riders deliberately violated race-based state laws, fought segregationist policies in public accommodation, and participated in “sit-ins” at all-white lunch counters. They were frequently targeted by local law enforcement with violence and incarceration. Though none was murdered, one of their buses was firebombed and another was boarded by counter-protesters who attacked and beat the nonviolent students.

Schwerner and Chaney Enter the Sights of the Mississippi KKK

Of the three men killed by Deputy Price and his cronies, both Michael Schwerner and James Chaney, a 1962 graduate of the Freedom Rides, were active members of CORE. Schwerner, a math teacher, left New York City to settle in Meridian, Mississippi, where he ran the CORE office and persisted, despite racial indifference and animus, in preparing Black Mississippians to try to register to vote. Andrew Goodman, new to the movement, arrived later. An undergraduate at Queens College in New York City, he was among the first groups of trained Freedom Summer volunteers to be sent to Mississippi.

Among the states, Mississippi had the lowest percentage of Black residents registered to vote – fewer than seven percent. Voter suppression had been so successful that in Issaquena County, which had a majority Black population, not a single voter was nonwhite.

CORE’s attempts to register new African American voters were initially ineffective due to long-established barriers to voting by racial minorities. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and quizzes on the content of the state’s constitution were just some of the tactics utilized to discourage and repress the Black vote.

Because of this execrable situation, CORE joined with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to form a steering committee, the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), to design a demonstration project that would shine a national spotlight on the plight faced by Mississippi’s disenfranchised Black community.

They knew what they were up against. Over the course of just one night, in early 1964, the KKK had organized a massive display of cross-burnings in 64 of Mississippi's 82 counties. The stakes were high, indeed.

The Mississippi Project: Freedom Summer 1964

Feeling the urgency of the moment, COFO sent out a nationwide call to organize a season of protest in Mississippi. Structured as a demonstration project, the effort – named the Mississippi Project – came to be known as Mississippi Freedom Summer.

COFO’s head was a young New York native named Bob Moses who had relocated to Mississippi to devote his time to voter registration. John Lewis, future long-term congressman from Georgia, at that time represented SNCC in Mississippi. He was optimistic about the prospects for making a national example of racism in the Deep South.

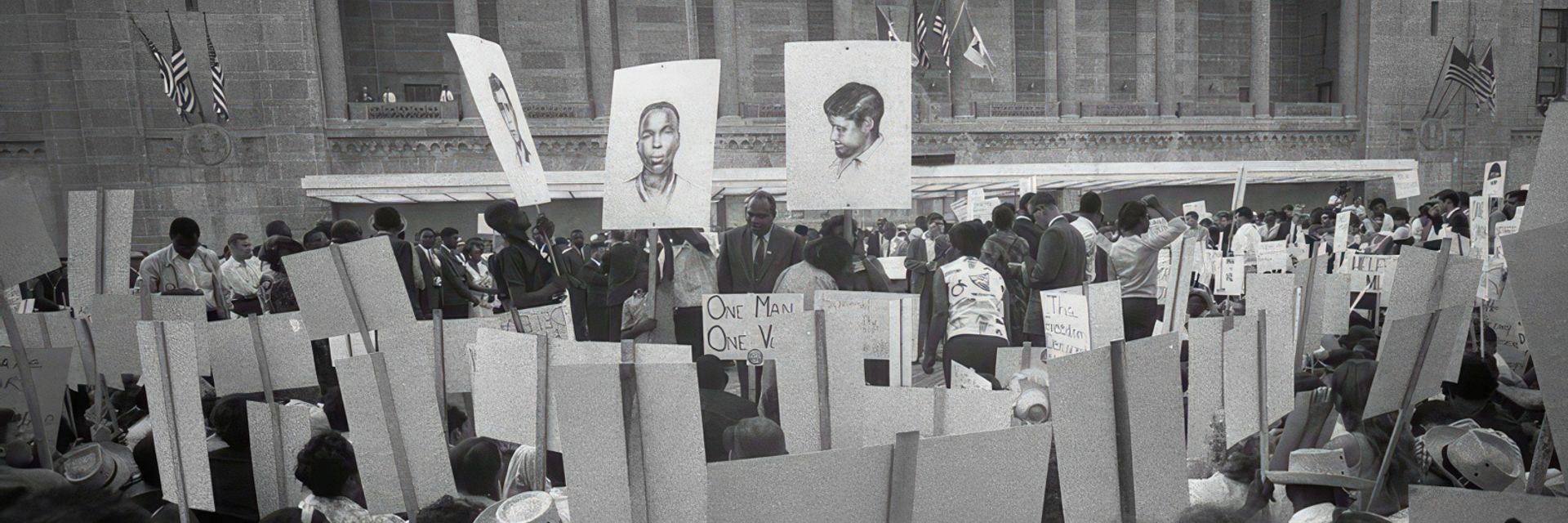

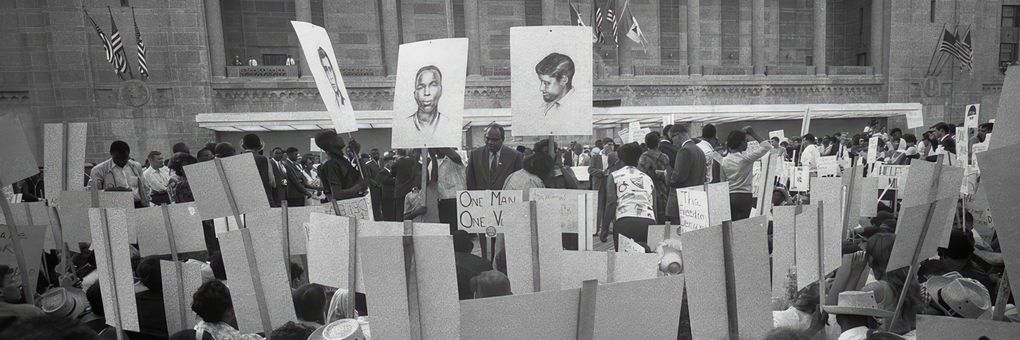

Civil rights activists demonstrate for the freedom to vote, 1964. (Source: Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress, via Wikimedia)

“If we can crack Mississippi,” Lewis proclaimed, “we will likely be able to crack the system in the rest of the country.” And so, the call went out to American college students to devote their summer of 1964 working for racial justice and freedom in the South. Training sessions were held over two weeks in June at the Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio. Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner all were in attendance.

What Were the Goals of Freedom Summer?

Freedom Summer had three strategic aims. These were to

- Legally register Blacks to vote in the state;

- Set up “Freedom Schools” to educate young people and prepare them for activism; and

- Establish the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as an integrated alternative to the white supremacist Democratic Party of the state.

Voter registration in such a hostile environment was the primary objective. A full 17,000 African Americans attempted to register over the summer of 1964, yet only 1,200 were successful.

Freedom Summer’s second goal was to improve education for Mississippi’s Black children while exposing the state’s abject failure in this responsibility. Mississippi’s overall spending for education was already the lowest in the nation, but even worse was its allocation to the segregated schools Black students attended – only a quarter of what white schools received. Impressively, the project’s audacious plan attracted more than 200 volunteers to stay in Mississippi as teachers.

The third goal was openly political: establishing the MFDP as an integrated alternative to the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party (MDP). To the activists’ dismay, the Democratic National Convention of 1964 seated the traditional MDP delegates. It took four years, till the 1968 convention, for Democrats to reject segregated delegations.

Was Freedom Summer Worth It?

The nation suffered through a distressing summer of 1964. It took from June to late August for the investigation into the disappearance of the three civil rights workers to progress from fear for their loss to grief when the bodies were finally recovered from the earthen dam. During that time, the nearly 1,000 volunteers who had traveled to Mississippi continued to work for fairness and freedom. They organized and educated, and many voices were raised against the all-too-apparent intimidation and violence of the forces of racism and oppression.

The remains of the blue Ford Fairlane owned by CORE in which the three civil rights activists were murdered. (Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

The federal government acted eventually, though many would say it was shamefully slow to respond to the atrocities committed by white supremacists in the South and elsewhere in America. The stark and brutal reality of virulent racism finally prompted President Lyndon Johnson to wheel and deal his way to two landmark bills, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Would the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act have become law were it not for the national revulsion at the brutal, premeditated murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi? Ironically, the heinous crimes of Cecil Price and his gang of racist thugs helped ensure the success of President Johnson’s signature legislative achievements. But it was the activists who risked – and sometimes lost – their lives in the struggle.

Freedom Summer was among the last major interracial civil rights efforts of the 1960s. In its wake, many activists were repulsed by the violence they had witnessed. In addition to the slayings of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, at least three other murders were documented that summer. There were also 35 shootings, four critical injuries, nearly 100 beatings, and more than 1,000 arrests of activists.

Later, the mood shifted further, as new and more militant protesters arrived on the scene, advocating “the old eye-for-an-eye philosophy,” which an alarmed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. opposed, because, he reasoned, it would “leave everybody blind.” Moreover, movements against the Vietnam War and in support of other urgent causes divided the attention of young activists. There was, to be sure, much injustice to protest in the America of the 1960s.

Many would say there still is.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party supporters demonstrating outside the 1964 Democratic National Convention (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia)