Two millennia ago, in the great cosmopolitan center of Alexandria, there lived a man named Hero, a scientific experimenter and inventor who developed breakthrough applications for steam hydraulics, wind power, and even programmable automatons. That he is little known now is a shame, since, like various polymath “geniuses” of later eras, his restless creativity and intellect drove him to invent scores of machines both practical and amazing.

◊

Can you imagine? A steam-powered energy source invented nearly 2,000 years ago! That’s about 18 centuries before James Watt is credited with inventing the steam engine, which sparked the Industrial Revolution. And, not only did the inventor of this remarkable ancient mechanical contraption create useful and groundbreaking machines, he was equally invested in designing implements of wonder that, for example, mysteriously appeared to refill wine goblets and even showed the gods opening doors to the inner sanctums of temples.

Such marvels would be enough to place their creator, Hero of Alexandria, in the pantheon of world-class – and presumably world-renowned – inventors. But don’t be concerned if he is unknown to you. Although he is now considered by many to be the Leonardo da Vinci or Thomas Edison of his time, most of his groundbreaking designs were lost to Western scholars for nearly two millennia.

Hero (also known as Heron) was a polymath who taught at the great Museion of Alexandria, a complex that included the fabled Library. It was here that his lecture notes were housed until the institution was destroyed several centuries later, taking with it the designs for his many inventions. Most of what we have learned of Hero comes from transcriptions of those documents made by Arab scholars and preserved after the destruction of the Library. His numerous inventions (at least 80 are recorded in his notes) included the first hydraulic-powered fire engine as well as the first deliberate use of wind power in a man-made machine.

What do we really know about Hero? Other than his lecture notes, we know tantalizingly little about this inventive genius. He was born in Alexandria to parents who were Greek emigrés, and he was clearly well educated in the arts and sciences. Beyond that? Not much.

In addition, he a distinguished mathematician who came up with a novel method of computing the area of a triangle, now called Hero’s formula, and his contributions to engineering and technology are nothing short of jaw-dropping. For more about Hero and his heady times, check out the MagellanTV documentary series Ancient Inventions.

Hero’s Technological Breakthroughs Include the First Steam Engine, the Aeolipile

Based on Hero’s rescued writings, we know that the scientist and educator had mastery of quite a broad range of subjects. These included, among others, Metrica, the study of measuring volumes and areas of 2-D and 3-D geometric shapes; Mechanica, the study of lifting and moving heavy objects; Pneumatica, the study of pneumatics, hydraulics, and other uses for air, steam, and water pressure; and Automata, the study of machines built to elicit reactions of wonder, particularly in temples of worship.

Much as a later genius, Thomas Edison, utilized insights from multiple branches of science in his many inventions, Hero used and synthesized principles of applied mathematics, physics, and other fields of study in formats that reveal numerous innovative designed solutions to engineering problems.

By some accounts, Hero invented over 80 novel machines, only a few of which were evidently constructed in his lifetime.

Of all his myriad inventions, perhaps the most notable is his design for a rudimentary steam engine. Called an aeolipile, it worked both simply and effectively. Harnessing the power of water heated to boil in a virtually closed chamber with two small vents, Hero was able to demonstrate that steam is created in an energetic transfer between two states of water, liquid and gas.

Source: Conservatoire national des arts et métiers, image by Rama, via Wikimedia Creative Commons

By positioning the vents on opposite sides of a spherical metal ball, and then angling the vents so that they forced compressed steam out in diametrically opposite directions, Hero was able to heat the water container and cause it to rotate in a circular direction.

More Inventions to Impress and Delight, from the Fire Engine to a Self-Refilling Wine Goblet

As a mathematician, physicist, inventor, and educator, Hero was clearly concerned with preserving his work, including his many mechanical devices, for future generations to study and apply. It’s tragic to consider that most of his work was lost for nearly two millennia.

Consider how useful an invention like the fire engine would have been had it been available prior to its reinvention – utilizing the same insights – in the 16th century. Hero’s fire engine was an early marvel of hydraulics. Constructed on a cart with wheels to make it mobile, the engine had a reservoir of water that could be forced up and out through a system of “pistons, cylinders, and valves,” creating a powerful jet of water that could be focused and directed in multiple ways.

If nothing else, Hero made a lasting contribution to science and medicine with the invention of the syringe. His understanding of the principles of air and liquid displacement allowed him to create a device that delivered a steady, controlled flow of liquid.

Hero sought to improve life for his fellow Alexandrians with practical implementations of the principles of hydraulics that he had discovered. But not all of his inventions were strictly utilitarian. An example that really stands out is the ever-needed invention of the self-refilling wine glass. Hero’s complicated design worked on the principle that liquids in a closed system seek a common level. As imbibers sipped their wine, the goblets, attached by a pipe to a common wine reservoir, would automatically reset to the level of the wine source.

Instruments of Wonder: The Illusion of the Gods in Hero’s Religious Inventions

Hero must have been deeply involved in the religious practices of Egypt under Alexandrian rule. But it’s hard to assess his actual spiritual beliefs from the “aids to religious practice” that he devised. This is because many of his mechanical inventions attempted to create illusions of divine intervention and activity in the temples of the day.

Some of Hero’s designs have evolved into tools we’re all familiar with. He described both an early odometer to measure large distances and a machine called a dioptra, a surveying instrument quite similar to those used today for the same purpose.

A prime example of these religion-oriented devices was the “automatic door opener” that was designed for use as part of a spiritual service. Using a hidden heat source that created steam pressure, and implemented with a secretive system of ropes and pulleys, the doors that separated the faithful from the temple’s holy altar would initially be closed; then, when pressure was sufficient, the doors would mysteriously open as if under their own power – or, more to the point, initiated by a divine force.

He also invented a coin-operated holy water dispenser and a self-powered portable fountain that appeared to operate on its own, not even needing an external water source.

Wind Energy Unleashes the Music of the Divine

Over a millennium before windmills first appeared in the Middle East and Europe, Hero had harnessed the wind – albeit on a small scale – to power a mechanical device for producing music. His invention, called a windwheel, used the currents of air flowing on a brisk day to power itself and thereby force concentrated gusts of wind through a series of pipes, which in turn created “music” of various squeaks, squawks, and whooshes, not unlike certain experimental music from our contemporary avant-garde.

Entertainment seemed to captivate Hero, and some of his most intriguing inventions were designed for audiences. He is known for designing a mechanical puppet show that portrayed the legend of Dionysus using only thread and weights that caused figures to move, gesticulate, and rotate.

He also devised what is considered to be the first programmed “automaton,” or robot. By “programming” a series of ropes and pulleys, he was able to make a wheeled cart move along a set course and perform a preset series of actions. How did it work? According to one writer for Ancient Wisdom, “the device was controlled by a series of ropes with knots tied in them. As the rope was pulled through the device, the knots moved levers which caused actions to happen on the miniature stage.”

The Revolutionary Tech Genius of the Ancient World

Like, say, a Nikolai Tesla, who dabbled in technology that would not be widespread for generations after he lived, Hero made connections that were well ahead of his time. And perhaps like current-day entrepreneur Elon Musk, founder of both Tesla, Inc., and SpaceX, he was a man with broad and genre-defying technological insights.

We have reviewed just a small sampling of Hero’s better-known inventions. There are many more. And beyond his mechanical tools and toys, he also created a substantial body of work as a mathematician, physicist, and engineer. There is evidence that he is the first person to conjecture that light always follows the shortest path from its source outward – and that shortest path is a straight line. (This realization possesses great applications, despite it being contradicted, in certain extreme cases, by Einstein.)

Hero was a revolutionary thinker whose great works were buried and largely forgotten in the generations after his death. Today we have the luxury of looking back on his works and pondering the great “what ifs”: What if his teachings had been preserved? What could have developed in Alexandria had the city not been sacked and burned by the Romans? What if access to Hero's voluminous work had been widely available to the scientists and creative dreamers who followed him?

Such ponderings, in their humble way, are in service to the inquisitive intellects of Hero and other great scientific thinkers. And, despite the millennia that have passed between his time and ours, we can see the value that rigorous scientific thought can bring to our own daily needs and desires. Insights can happen anywhere. It’s up to us to nurture and preserve them as best we can.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

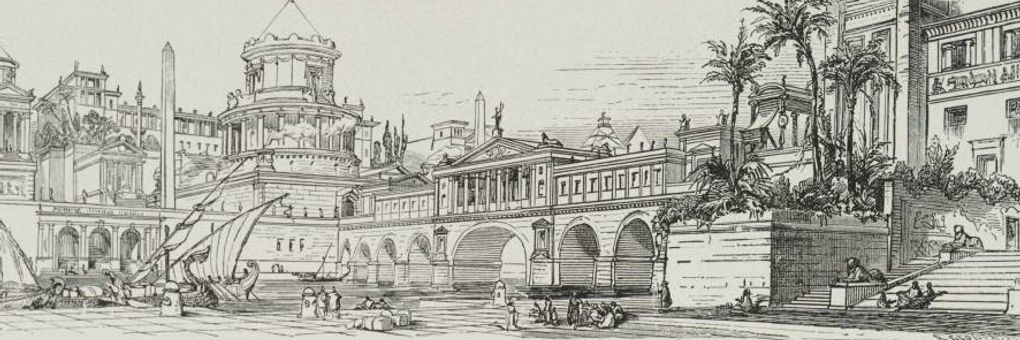

Title image: Line drawing of a scene from Alexandria in ancient times by Adolf Gnauth via Wikimedia Commons.