In WWII, army personnel on both sides of the war became drug test subjects to create “super soldiers.” Hitler may have been the most drugged military leader of all time.

◊

World War II was the costliest and most destructive military conflict in history. For all the damage it wrought, it was also the most technologically advanced war up to that point. Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Japan) and Allied forces (the U.S. Great Britain, the Soviet Union) both endeavored to bring to war the most state-of-the-art weapons and military systems.

Nazi Germany designed V-2 rockets, the first long-range ballistic missiles, to pummel London during the Blitz. Radar and sonar, first developed by Britain, were widely utilized to detect enemy aircraft and naval vessels. And, of course, the United States deployed atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which contributed to Japan’s surrender to the Allied forces September 2, 1945.

Less known, but equally widespread during the war, were continuous attempts to improve the basic unit of combat, the fighting man. If weaponry could be improved through research, why not humans? So, drugs were created and introduced, often with negligible testing, to boost soldiers’ stamina, keep them awake and alert longer, and mitigate the debilitating effects of shell shock.

This is the story of how military leaders on both sides of the conflict fed their troops drugs with the goal of creating “super soldiers” to give them a winning advantage in the war.

For more on the drug-addled Third Reich, check out the MagellanTV documentary Blitzed: Nazis on Drugs.

The Beginnings of the (Pro) Drug War

The Nazi Party took control of Germany in 1933 with the philosophy that Aryans, the Party’s perceived “true heart” of the German people, were superior in every way to non-Aryans. And Hitler professed his belief that Germans would dominate its adversaries through their very nature. He stressed health, sports, fecundity, and militarism as the means to create the “master race” and prove other countries and their people to be lesser rivals.

Given his lofty – and racist – aims, he and the Nazi Party were disappointed by their showing in the 1936 Olympics, held in Berlin. Even though Germany won the most medals that year, the Americans posted a strong second-place finish. More shocking for the Nazis, Black American athlete Jesse Owens won more gold medals – four – than any other single competitor.

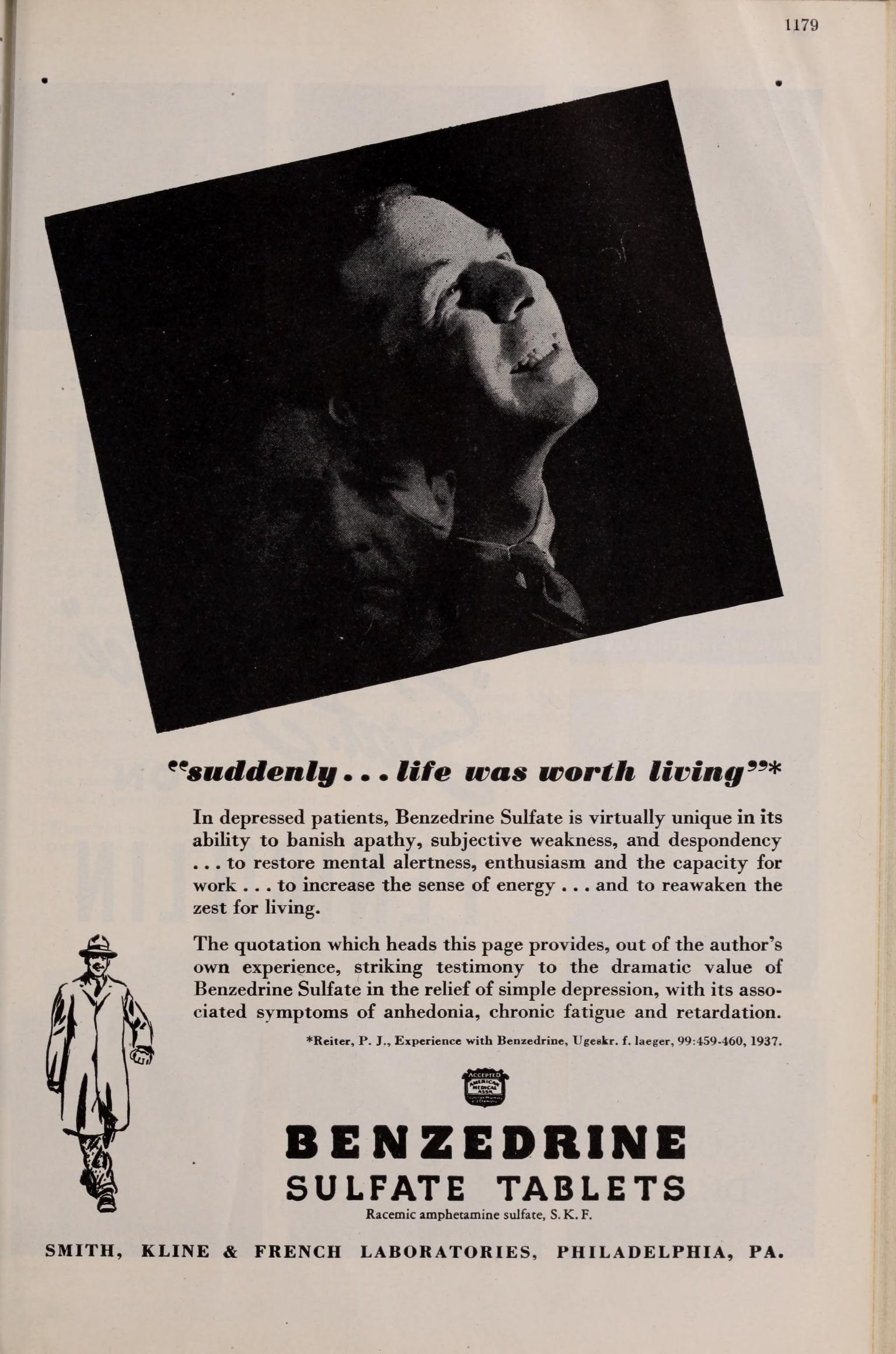

The Germans were certain that the U.S. athletes had a hidden advantage, and that advantage, they decided, was performance-enhancing drugs – what we would now call “doping.” And they weren’t entirely wrong. According to Time magazine, some athletes took the U.S.-made stimulant Benzedrine during the Games. Among them were competitors from a number of countries, including Germany and the U.S. (though not Owens).

The German chemist Friedrich Hauschild took it upon himself to create a stimulant for his state as well. Within one year of the Games, he studied ephedrine, a derivative of ephedra, a plant used in Chinese medicine, and succeeded in creating a synthetic version – methamphetamine – that was released to the German public under the name Pervitin. Although the Nazis had promulgated strong policies against the use of drugs, they got around that stance by marketing Pervitin as a mood enhancer. They even disguised it inside chocolates as a dietary supplement to curb hunger and help housewives lose weight!

Surprise – and ‘Speed’: Ingredients of the Nazis’ Blitzkrieg

Pervitin – issued by the German military to its troops in the air, in tanks, and on the ground – quickly became essential to the Nazi strategy for success. Once it became available in large quantities, it was tested on troops and was found to remove “natural tiredness.” So, from the early stages of the war, Pervitin accompanied the troops to keep them up for days, to enhance their confidence, and to boost their morale in the face of the horrors of war. Two hundred million doses of methamphetamine were distributed by the Germans over the course of the conflict.

(Source: Komischn via Wikimedia Commons)

In the German offensive of 1940, German troops were ordered to stay awake for three days as they improbably marched westward through the mountain passes of the Ardennes, signaling the beginning of the Battle of France. This took the countries of Western Europe by surprise, since the Germans’ speed in moving personnel was unprecedented, and because the tank crews didn’t stop moving till the invasions were complete. Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and finally France all fell to the Pervitin-powered stormtroopers.

The British Take Note, and the Allies Climb on the Amphetamine Express

Although the Axis powers were first to use this class of drugs, Britain’s Royal Air Force discovered the Germans’ secret when they took possession of a downed German airplane and discovered Pervitin stocked in the airmen’s cabin. Not wanting to be disadvantaged in the raging conflict, the U.K. approved 72 million doses of the amphetamine Benzedrine for use in all branches of its military. Dwight Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied forces in the Mediterranean Theater, approved 500,000 Benzedrine tablets for his troops to see them through the 1942 landing on North Africa.

Separately from Germany, chemists in Japan used ephedrine as a base to produce one billion doses of methamphetamine, which they called Philopon, between 1939 and 1945. This led to a problem in postwar Japan, with over half a million addicted to the substance.

Although these drugs were tested on military volunteers and, in the case of Germany, on prisoners in concentration camps, little thought was given to their negative side effects. In Germany, risks of Pervitin were noted as early as 1939 but were ignored. In fact, Otto Ranke, the head of Nazi Germany’s Institute of Defense Physiology, which conducted the testing, was also a regular user, and noted its wondrous effects in allowing him to work nonstop, with no rest and no fatigue, for periods between 36 and 50 hours.

In the U.S., amphetamines were administered to troops prior to drug testing being undertaken. But Allied forces were not nearly as demanding of their troops as were the Nazis. Among the Allies, primarily Britain and the U.S., the popularity of Benzedrine had less to do with the science of fatigue than with the drug’s mood-altering effects. Taking “go-pills,” as they were often called, boosted confidence, increased aggression, and elevated morale. All these things supported the aims of the Allies in the war.

British infantrymen in WWII (Source: Imperial War Museums via Wikimedia Commons)

It took years, but finally the downsides of “bennies” and “meth” became glaringly apparent. The drugs were highly addictive, caused heart palpitations and even heart attacks, induced paranoia and psychosis, and were responsible for poor judgment in high-stress situations. To come down and allow troops to sleep, they often needed “no-go pills” in the form of barbiturates. Over the entire span of WWII, American troops took between 250 and 500 million Benzedrine tablets, and an estimated 15 percent of troops were regular users. In many ways, WWII required sped-up responses without downtime, and amphetamines became one of the military’s basic necessities.

Amphetamine use can lead to dependency, even addiction. In the U.S., after the war, hundreds of thousands used “pep pills” to combat lethargy, depression, and weight gain. Even today, between 250,000 and 350,000 Americans are addicted to speed.

Hitler: Riding the High of War till the End

Ironically, considering he extolled healthy living so frequently, Adolph Hitler was himself a heavy user of both legal and illicit drugs. In fact, as the war raged on, he became increasingly dependent on them. When supplies ran out, he went through a debilitating withdrawal that may have affected his decision-making.

Hitler started out easy. He became aware of a physician named Theo Morell through his photographer Heinrich Hoffman, who had received vitamin shots from the doctor. Morell began treating Hitler with daily vitamin injections that cured him quickly of a nagging intestinal disorder (stories abound of Hitler’s incessant farting). The Führer was so impressed he offered Morell a job as his personal physician, and Morell, a Nazi since 1933, enthusiastically accepted.

The doctor continued with daily “boosts” of vitamins, but soon added Pervitin to the regime, and Hitler liked the effects. Pervitin made Hitler feel bolder, more confident, even more charismatic. He took Pervitin daily throughout the war, and soon Morell, who was a bit of a quack, was adding stronger concoctions to Hitler’s daily drug “cocktail.”

To the base of methamphetamine (in the form of Pervitin), Morell added injections of cocaine, followed by an opiate – that is, another addictive drug, this one closely related to heroin – called Eukodal. Hitler’s reliance on these drugs to stay energized and focused had a significant impact on his performance as leader of Germany.

Historians note that his drug use caused him to become increasingly paranoid and irrational, resulting in his erratic decision-making. His drug use also began to take its toll on his physical health, leading to a weakened and exhausted state that further impeded his ability to lead. Many historians agree that his dependence on these drugs was one of the contributing factors to his eventual downfall.

Allies bombed Berlin and destroyed the labs that manufactured Pervitin in late 1944. After supplies dried up, Morell ordered Hitler’s staff to comb the city’s pharmacies to gather as many boxes of Pervitin as they could round up.

When Hitler went into withdrawal from the sudden loss of supplies of his favored drugs, his mental and physical health deteriorated. Observers noted that he trembled and sometimes had herky-jerky movements. Some of these symptoms have been attributed to the onset of Parkinson’s disease, but this has never been confirmed. The tics could just as easily have been due to the effects of the combination of drugs and, later, the effects of withdrawal.

Consuming cocaine and heroin together is now called an “8-ball,” and is known to be highly toxic and sometimes fatal. Hitler’s tolerance was such that he took both cocaine and meth along with the opiate Eukodal and managed to survive.

The End, and the Aftermath of the War with Drugs

Near the end of the war, Hitler’s paranoia became all-consuming. In March 1945, he issued a proclamation titled “Destructive Measures on Reich Territory.” Also known as the “Nero Decree,” Hitler – who once had dreamed of building a “Thousand Year Reich” with its grandiose capital building in Berlin – demanded that German civilians and military participate in the all-out obliteration of Germany’s infrastructure. Clearly, he could not see a future for anyone at the end of the war, including himself. It is a miracle there was anything but rubble remaining once the Germans surrendered in May 1945.

Yet the legacy of Pervitin and Benzedrine far outlasted the war. Pervitin was freely manufactured in Germany for decades. Only in 1980 were its addictive qualities acknowledged, and production ceased. In the United States, Benzedrine – or bennies, speed, or crank – became a part of the American postwar underground. Through veterans, its use slipped into the worlds of motorcycle gangs, long-distance truckers, jazz musicians, Hollywood, and the so-called Beat Generation. It is sobering to note that such public figures as actress Judy Garland, writer Jack Kerouac, and artist Andy Warhol made their reputations on speed, in some cases in concert with barbiturates, or “sleeping pills.”

Benzedrine was offered as a treatment for depression, as well as weight loss, in postwar America. (Source: u/Juno-40054-69-1 via Reddit)

Nowadays, it’s hard to imagine masses of people all taking daily doses of speed habitually to get through their days, but such was life in developed countries all over the world in the decades following World War II. Only in the past couple of generations has drug testing exposed the many downsides to chronic usage of amphetamines, and methamphetamine has been recognized as clearly dangerous and addictive. But the dangers were virtually unknown to armies in the 1940s. In their quest for superiority, militaries on both sides of the war produced “super soldiers” who turned into postwar addicts.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on various topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

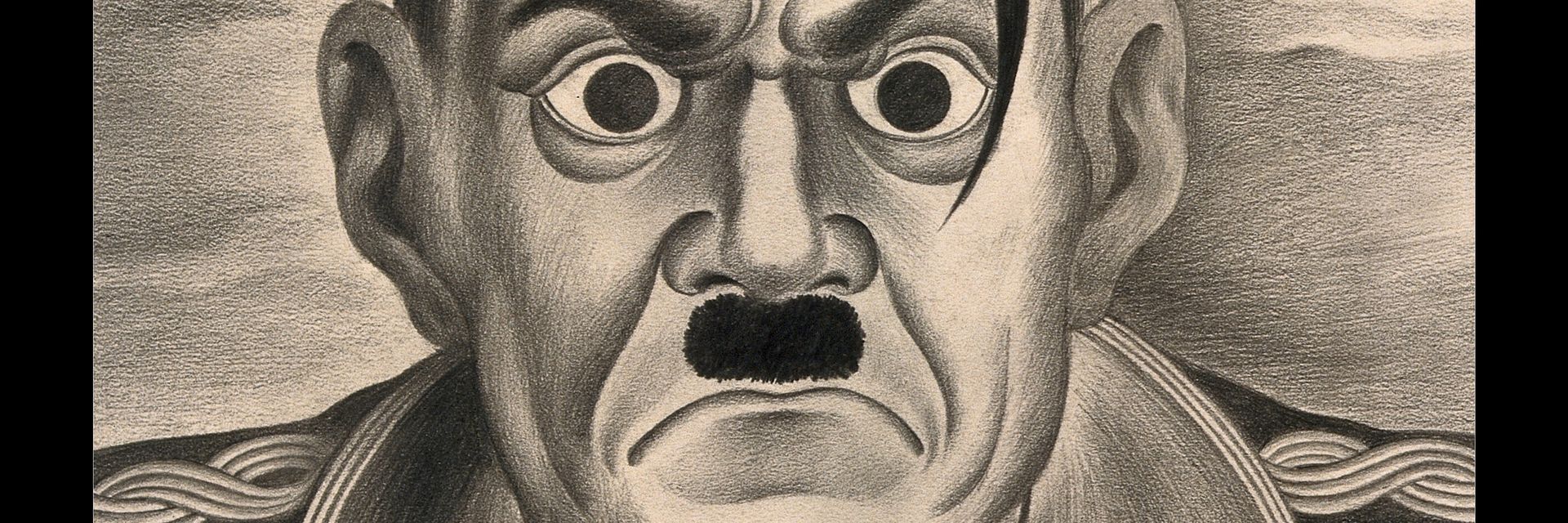

Title Image: Caricature of Adolf Hitler by Albert Lloyd Tarter, 1940s. (Source: Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia Commons)