Alfred Southwick sought a humane way to execute criminals with his invention of the electric chair, but cutthroat competition between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse was anything but humane when Edison used his rival’s AC electric current in the chair to demonstrate its supposed danger for widespread use.

◊

The late 19th century was a halcyon time for ingenuity. New inventions were being developed at a dizzying pace, and there was a race to develop new-fangled uses for the mysterious power of electricity. Inventor Nikola Tesla, an early master of the potential of electrical power, sought to design and construct methods to capture, package, and transmit alternating current (AC). Tesla gave us the first AC motor, along with AC generation and transmission technology, as well as other less successful inventions.

Watch The Chair to learn more about the first execution using the device. Now streaming on MagellanTV!

Tesla’s innovations deeply influenced the thinking of inventor and entrepreneur George Westinghouse, who sought to parlay the fortune he’d amassed while at the helm of an influential railway services company into the race to own the first successful electricity utility. Westinghouse squared off against the inventor and all-American icon Thomas Alva Edison, whose own research into electricity relied solely on direct current (DC), a less-powerful but also less-dangerous method for the transmission of electricity.

To enter the field, in 1886 Westinghouse funded the first AC power transmission system, near Boston, using the Tesla-inspired generators the inventor had built. But his goals were much larger. George Westinghouse wanted to win the so-called “War of the Currents” against Edison, and gain acceptance of his preferred electrical current mode as the standard.

And that’s where the whole problem started.

'War of the Currents' or War to the Death?

Westinghouse contended that his AC system was superior to DC due to its commanding advantage in sheer power transmission. DC could not generate nearly enough power to compete. And AC had one more extremely attractive advantage: the current traveled much further without degradation of its voltage strength.

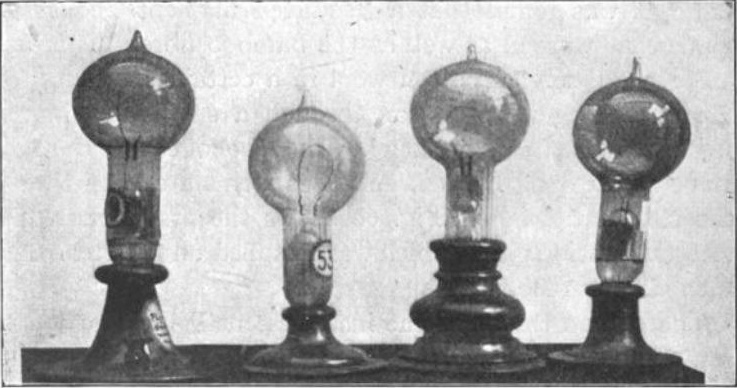

Where Westinghouse made a persuasive case based on facts, the avuncular and well-trusted American inventor Thomas Edison already had Americans in the palm of his hand due to, if nothing else, the invention of the electric light bulb. And the story he told alarmed listeners. He extolled Edison Electric products as being the safest products in the industry, while Westinghouse’s products were potentially unsafe, even lethal at the upper ends of AC power.

Edison incandescent bulbs (Source: William J. Hammer, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

To make things worse, stories were circulating about people who had died unexpectedly – and almost instantly – by touching an AC power source, accidentally or, in one case, on purpose. One night in 1881, at a generator station for arc-light power in Buffalo, New York, an inebriated man found his way – most likely by mischief – into the generator room and proceeded to touch the “live” equipment. Big mistake! Or was it?

What’s the difference between AC (alternating current) and DC (direct current)? It’s all in how electrons are harnessed. Direct current flows only in one direction, and alternating current flows back and forth, which allows for both higher voltage as well as greater distribution along a network.

The coroner’s report noted the death, labeled “accidental,” was likely instantaneous. The report made the rounds, the mode of death being as unusual as it was, and it came to the attention of a local Buffalo dentist and inventor. Alfred Southwick, it turns out, was opposed to hanging as a means of execution and sought a more “humane” way for the state to put people to death. He wondered if this exposure to electricity might ease the brutality and often-botched results of hanging.

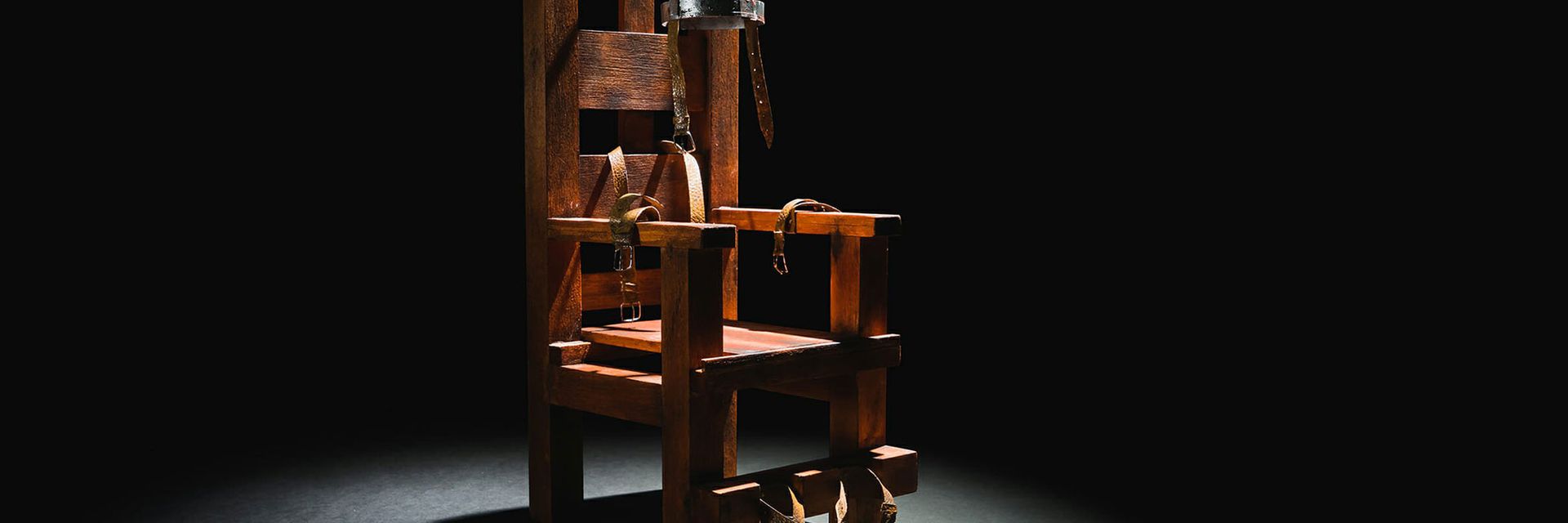

So, he designed and patented a forbidding-looking device with straps and electrical wires, which he successfully tested on animals. As he was a dentist, it should come as no surprise that his invention looked rather like a dentist’s chair.

The Electric Chair: Invented by Southwick, 'Perfected' in Thomas Edison’s Lab

Alfred Southwick invented the electric chair, but his was not the ultimate design. Once New York became the first state to proceed with a usable electric chair (ostensibly for humanitarian reasons), a commission was set up to approve its design. The commission included Southwick and, somewhat surprisingly, Thomas Edison, who had publicly opposed the cruelty of the death penalty. Apparently, Edison was motivated less by sympathy for the condemned than by pure industrial envy of his competitor in electrical transmission and supply, George Westinghouse.

Westinghouse was also opposed to the brutality of hanging, and, it turned out, not a fan of execution by electricity. In fact, he refused to sell any of his AC generators to public officials, lest they be used for the purpose of execution. But he couldn’t stop Edison, who had his team fan out over the region to look for “after-market” Westinghouse generators that might be available.

And the sparks did fly. (Beware, some descriptions that follow could be rather disturbing.)

Edison’s “big idea” in his war with Westinghouse was to connect his competitor inexorably to danger, and death. So he promoted the idea of calling electrocution by a different name, “Westinghousing.”

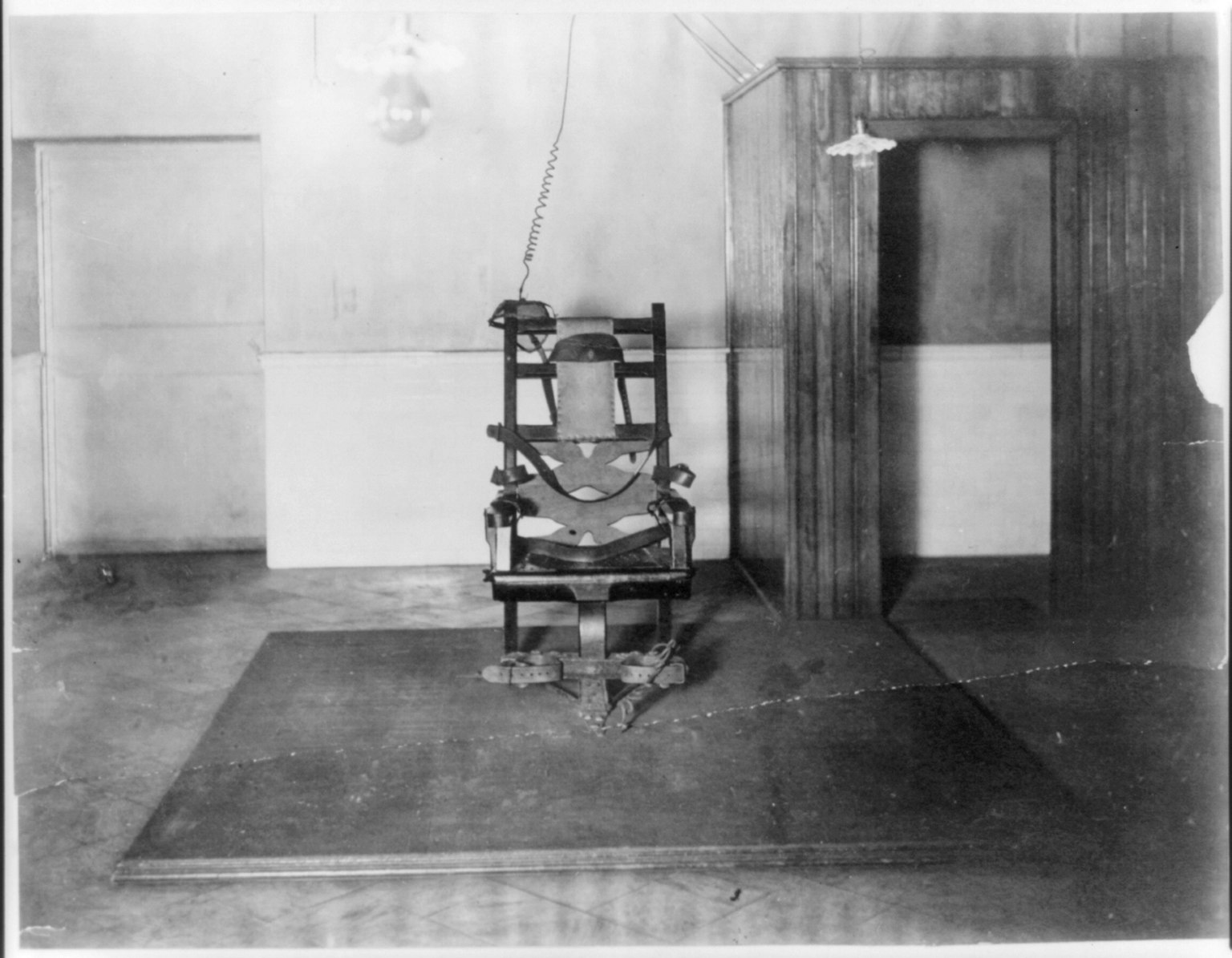

It wasn’t easy to build a machine for killing people, as Edison and his team were soon to discover. Even though the idea was simple – electrify a body with a live electric charge – no one really knew how to do it. How would you choose the level of charge, for example? And how long should the charge last? Should there be more than one electrical charge, and if so, how many would be optimal?

Electric chair, 1908 (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia)

So the Edison team set out to experiment on living creatures. Scores of stray dogs and cats were sacrificed to the cause. And when the team was challenged to set a reliable electrical charge to dispatch a human, it included among its prey farm animals such as pigs and calves. Eventually, the Edison people sought a still larger animal upon which to test a lethal electrical charge. They procured an adult horse (supposedly a lame one) and attached electrodes to its head and the base of its spine. Alas, the test was a “success,” and Edison felt confident that his team had discovered the most effective procedure to painlessly put an inmate to death.

The Electric Chair Is Pressed into Service . . . by Edison

While Edison was charging up his chair with a Westinghouse generator and simultaneously proclaiming the Westinghouse Electric Corporation as dangerous for powering a family’s home, George Westinghouse was neither silent nor quiescent. He proclaimed his distaste for the stunt and attempted to stop, or at least delay, its use on condemned prisoners.

Westinghouse put his money to use in opposing the use of Edison’s product. He objected strenuously to the electric chair’s use of AC current and to the appropriation of a not-exactly-ethically-obtained Westinghouse generator in its design. He detested Edison for employing underhanded methods, and sought to stop executions using electricity altogether.

The execution of William Kemmler, 1890 (Source: Ernest Clair-Guyot, Le Petit Parisien, via Wikimedia)

When convicted axe-murderer William Kemmler was made first in the queue to be the chair’s premiere victim, in 1889, Westinghouse hired the convict a defense team that argued execution using electricity constituted “cruel and unusual” punishment. However, given the extreme public interest in the new-fangled power of electricity to help, heal, and harm – and given the fact that Kemmler had been convicted of the extremely brutal murder of his erstwhile beloved – it’s not surprising that the appeal filed on the killer’s behalf was unsuccessful, and he was sent to the chair in August 1890.

Although William Kemmler was the first to die in the electric chair, he was not the first selected for this fate. That distinction fell to Joseph Chapleau, another convicted murderer whose sentence had been commuted to life imprisonment after appeal. Kemmler, despite his deep-pocketed defense, was not as fortunate.

'Great God, He Is Alive!': A Botched First Effort for the Electric Chair

Kemmler’s execution was a horrifying example of Murphy’s Law. Everything that could go wrong, did, to gruesome result. Despite Edison’s assurance that the convict would get 1,000 sure-fire volts of electric death, the first charge only delivered 700 volts for 17 seconds, before the generator malfunctioned and had to be reset. Nonetheless, the charge stunned Kemmler into unconsciousness, which the assembled crowd mistook as success.

As early electric-chair designer Alfred Southwick crowed, infamously, “We live in a higher civilization from this day on,” someone else shouted, “Great God, he is alive!,” and the medic attending agreed. Incredibly, the horrific scene then went from bad to much, much worse.

In the confusion of that moment, the still-struggling Kemmler was jolted with a stronger charge of 1,030 volts for well over a minute. That’s when the good feelings ended, and fast. Kemmler was burning alive. Sparks flew from his face, he sweated blood, and smoke escaped from the crown of his head. Attendees could smell the singed skin and hair – and, still worse, the odor of boiling human excrement filled the room. Numerous attendees were nauseated by the smell as well as the sight, and had to rapidly escape the scent of death.

“They would have done better with an axe,” commented Westinghouse, with a mix of disgust and mordant wit, after hearing news of the execution. After all, Kemmler was an axe-murderer.

Despite this macabre scene, the official reaction was that this mode of execution would suffice, and more electric chairs began to be produced for sites around New York State and, eventually, to 26 other states.

The End of the History of the Electric Chair, and its Legacy

Looking back, it’s ironic to think that the movement to create this instrument of death was initiated by people who opposed the brutality of capital punishment as it was then practiced. They actually believed that electricity was the means to less cruel and inhumane executions. And, through a ghoulish process of trial and error, the “miraculous” electrical power that made executions possible was wrestled under control and became less unusual (if not much less cruel).

The industrial war between Edison and Westinghouse raged until 1893, and Westinghouse’s AC prevailed. That year, the Niagara Falls Power Company chose alternating current over direct as a means to transport the electricity generated at the Falls.

State-approved electrocution came under increased scrutiny through the 20th century. Eventually, the same controversy arose surrounding the electric chair as had dogged the practice of hanging a couple of generations earlier. Opponents of execution by electrocution sought to replace it with the “more humane” practice of lethal injection, which is now the standard across the U.S.

And so it continues. The quest to impose capital punishment is now opposed by those who believe that lethal injection is unconstitutionally cruel and inhumane. Will someone promote a “less barbarous” alternative to execution by injection? As long as there’s a death penalty in the U.S., someone is sure going to try.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Electric chair (Source: fergregory, via Adobe Stock)

(Editor's Note: Originally published in May 2019, this article has been slightly revised.)