The technology of producing daily newspapers has evolved dramatically over the past three centuries, from Gutenberg’s printing press through the Mergenthaler linotype machine and the computer to today’s digital revolution in news distribution. Along with those changes, the mechanics of reading the news has evolved too, from hand-held papers to hand-held electronic devices. But is reading the news fundamentally different than it was, say, a century ago? Fellow readers, let’s examine the entwined phenomena of both producing and consuming the news.

◊

Congratulations on cutting through the online clutter to find this newsworthy (I hope) article on the news. I am pleased to lead you on this voyage of discovery along the digital pathways that connect the words I type on my keyboard to your eyes, for your enjoyment.

Do you find the act of reading the news pleasurable? I mean, as distinct from hearing or viewing it in its many other forms of transmission, including radio (satellite and terrestrial), television (over-the-air, cable, and satellite), podcasts, and more. If so, you’re in good company. A recent survey found that over 69 percent of Americans read the news in one way or another: print, computers, and hand-held mobile devices. That translates to 227 million news-literate Americans. Out of nearly 330 million Americans, that’s no small beans.

(Source: Stock image, via Yale University Press)

Similar figures hold for readers outside the U.S. as well. Worldwide, it’s estimated that 2.5 billion people read a newspaper in print regularly, and the number nearly doubles when also accounting for online readership. The highest levels of readership tend to be among Western Europeans and North Americans, although Southeast Asian countries including Japan, Hong Kong, and South Korea also boast extremely high news readership

Now, I’m an inveterate news junkie who loves to read widely. You might say printer’s ink runs in my blood, as I used to be a print journalist. These days, writing exclusively for digital consumption, I suppose the metaphor no longer holds, though lots of printer’s ink is still spilled daily to produce physical newspapers. In fact, while there is a crisis brewing in the high-stakes business of producing a daily paper, and in the overall health of papers in general, printed newspapers still hit the home doorsteps of millions of grateful (and sometimes irate) readers around the globe.

If I haven’t yet made it clear, I’m grateful you’re reading my article right now. We share a bond not only of (one-way) information distribution, but a love for reading, in whatever form news “copy” arrives. Let’s celebrate that bond by taking a quick look at how newspaper production has changed over the centuries, and how it’s now changing in ways more numerous and rapid than ever before.

The Beginnings of the News Business

Utilizing the groundbreaking technological advances of Gutenberg’s printing press and subsequent inventions such as movable type, the first newspapers appeared in the early 1600s. These hand-printed and -assembled newspapers sprang up in such countries as Germany, Holland, and Belgium and were published weekly. It took about another century for the first English-language paper, this one a daily, to appear in the bustling metropolis of London, in 1702.

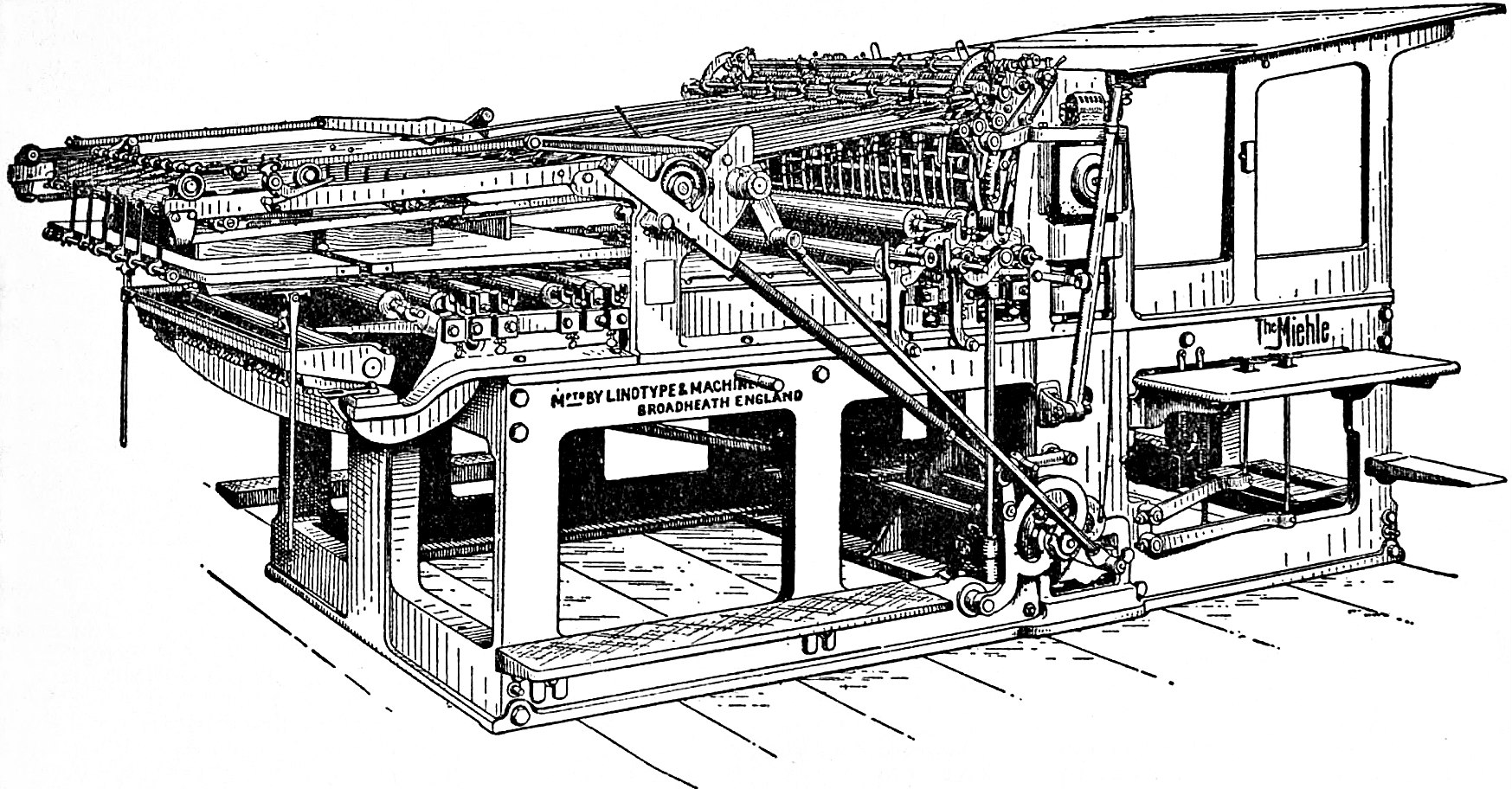

Miehl two-revolution cylinder printing press (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The advent of movable type made newspapers possible. Rather than setting each page separately to prepare for its printing, one page at a time, movable type sped up typesetting, page production, and printing. Later advances, such as the introduction of the iron press (1798) and the development of cheaper paper stock made from treated wood pulp (1840), further simplified production of newspapers and, by lowering per-copy costs, made them more accessible to a wider audience of readers.

By the late 19th century, printers had figured out how to take large rolls of newsprint stock and print continuously on both sides. The Industrial Revolution advanced newspaper production to the point that daily papers were now a feature of cultural evolution, and every city and town had at least one paper delivering up-to-date and engaging news articles.

The Timely Invention of the Linotype Machine

However, there was still a big problem to overcome, which was that page production and printing were frustratingly slow processes. Even with movable, reusable type, each character had to be selected from storage boxes, laid out in order, and fully assembled prior to the press impressions. Despite well-trained specialists – typesetters – there was a limit to how quickly a paper could be produced.

Numerous solutions were proposed, but none worked effectively to quicken page production. That is, until the late 19th century, when, in 1885, businessman and machinist Ottmar Mergenthaler filed papers with the U.S. government to patent his new contraption, which he dubbed the “linotype.”

Its main advantage over the venerable system of movable type was that, using hot metal, it could create an entire line of type at a time. (Hence, the “line o’ type” machine.) Through the means of a complicated (but, to our eyes, deceptively simple) keyboard that a typesetter could be trained to operate, an entire line of newspaper copy, called a slug, could be created in the time it formerly took a movable type operator to set a few letters in the compositor.

The progress symbolized by this change can hardly be overstated. It tripled the speed of page composition, so that what had been a full day’s job could now be completed in a matter of hours.

The “Daily Miracle” and the Linotype Machine’s Success

Freed from the drudgery of the character-by-character layout of movable type, typesetters now produced slugs in a matter of minutes and could speed through page after page of the stories and advertisements that made up newspapers then, and now.

No less an eminence than inventor and cultural icon Thomas A. Edison took a tour of an upgraded newspaper production plant and dubbed the linotype machine “the 8th wonder of the world.” (And Edison himself knew a thing or two about so-called “8th wonders”!)

At first, there was concern that this new device would diminish the number of (human) typesetters employed at news presses everywhere, but this concern turned out to be insignificant in the face of bristling capitalistic energy. Instead of less work, publishers instead increased production threefold, expanding the number of editions and introducing the novel concept of evening newspapers.

Edison not only promoted linotype, but his innovative work also allowed newspapers to expand. His own invention of the electric light, with its constant and steady illumination, made evening reading more pleasurable and more widespread.

The novelty of widespread news sources, and the reliability and burgeoning number of newspapers, came to be known as the “daily miracle.” Its democratizing influence in the U.S. and across the developed world would be hard to overstate.

Author Luc Santé, in a 2019 New York Times Magazine essay, described the 19th and 20th century dominance of printed newspapers as a “modernist” invention. It was meant to succeed in creating a community by democratic means (and arguably did, for a while), as newspaper journalists and editors sought to address all levels of society.

Girl reading newspaper reports of the Moon landing, 1969 (Credit: Jack Weir, via Wikimedia Commons)

Newspapers encompassed a range of subjects, from the events of the day to book reviews and comic strips. This essentially furthered the democratization of society at the time, with the goal of uniting a community behind the standards embodied by the paper’s ethos (including its advertising content and editorial opinions).

The moderating civic function of many metropolitan dailies made newspapers of the time “pillars” of their communities. They provided continual service to each town and city and, in many cases, became their area’s “standard-bearer” and leading light of both culture and commerce.

So . . . what happened?

The Newspaper in the Digital Age

These days, to me at least, printed newspapers seem anxious, even nervous. They appear to have lost a lot of weight, both physically and psychically. You’ve noticed how skinny they’ve become, right? Considering how many have changed ownership in recent years, they have even come to resemble orphans, desperate to find a stable home amid so much clutter, static, and competition from emerging alternatives.

With the exceptions of just a few major players – including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal, plus maybe a handful more – newspapers are barely a shadow of their former selves. Perhaps they weren’t nimble enough to make the transition from anchoring institutions of their communities to being among a variety of choices on the menu of media options.

You certainly can’t blame the hard-working, long-suffering linotype machine, which was put out to pasture in most places by the early 1980s, replaced by computers that sped up the pace of production. The “computer revolution” of the 1980s helped writers write, editors edit, and page designers compose entire pages photographically, transforming the basic unit of page production from the linotype’s slug to the computer’s entire page.

I suppose you could blame the computer, but that seems misdirected. Instead, let’s blame the Internet.

Reading Differently

The dawn of the digital age arrived in the mid-1990s, and it was truly a watershed. Seemingly overnight (okay, it took a couple years) our home computers went from “dumb” terminals to “smart” machines, connecting us to the world via our fingertips.

I am old enough to remember using the Internet for the first time. After a few years of accessing BBS “bulletin boards” to communicate with other users, the World Wide Web appeared, and suddenly we could visit “web pages” across the entire world in a virtual instant. (I mean, depending on the loading speed of your modem, of course.) The first site I visited on the World Wide Web, perched in my Los Angeles apartment, was the Louvre. It was mind-blowing to comprehend that I was viewing images directly from Paris, France, and could do so at any hour.

Now, according to Luc Santé’s essay, “a majority of consumers around the globe opt to get the latest word from their screens.” So, reading hasn’t disappeared; it’s just that the experience has been transformed. The phenomenon of reading online “content” is different from reading print, as you, my online reader, well know.

But that hasn’t made reading print obsolete – at least not for now, or for the foreseeable future. As my friend Murray has remarked, there’s something about the physicality of holding a stack of pages (in the form of a newspaper or book) in your hands that can’t be supplanted by whichever hand-held device you prefer – even one called a “reader.”

Online life, along with online versions of newspapers and even this online journal we refer to as the MagellanTV articles page, is the “new norm” for engaging our eyes and our imagination. It’s undeniably a more active – and interactive – environment than print (for better and worse).

It’s possible to become absorbed fully in an online article and to follow its argument from beginning to end uninterrupted. But I bet that’s not how you’ve been reading this article. Hyperlinks bring in more opportunity for visual distraction, and even page design can carry your eyes from words to illustration, or to whatever may lie a click or three away.

Reading in the digital age is, to me, no less a joy than reading printed type, but it’s a different kind of joy. Perhaps the best hope is that we can live, and thrive, with both. Distinct but related, the commonality is communication.

Thanks for making it to this endpoint. The opportunity always exists – as it does with reading a printed newspaper – to continue reading, or to amuse yourself in any number of ways. And that’s the pleasure of the “daily miracle” of newspapers, and writing, in both our stationary and our mobile lives.

Ω

Editor's Note: A paragraph regarding an expired MagellanTV documentary (Linotype: The Film) has been removed from this article.

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image Credit: Roman Kraft, via Unsplash