In March 1865, President Abraham Lincoln made a two-week visit to the enormous Union Army camp at City Point, Virginia, at the doorstep of the besieged Rebel capital of Richmond. The day after Richmond fell to U.S. troops, Lincoln left City Point for an impromptu, open-air tour of the captured city. At enormous personal risk, Lincoln’s public visit symbolized the reconciliation he desired for the nation.

◊

By the spring of 1865, City Point, Virginia – a spit of land on the James River 20 miles south of Richmond – was the site of a sprawling Union Army encampment and a busy harbor for Navy vessels.

Union forces settled there in early 1864, creating an enormous depot of men and matériel as part of General Ulysses Grant’s design to capture the South’s Civil War capital. And it was where, in March 1865, President Abraham Lincoln, at Grant’s invitation, decided to spend his first vacation from Washington, four horrible years after he took office.

By then, Grant’s coordinated war strategy had steadily crushed the Confederate forces. William Sherman’s western troops had swept through Georgia and the Carolinas and now sat just south of City Point waiting for Grant to flush Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from Richmond, where it had holed up the autumn before.

So it was with no small sense of hope for the war’s approaching end that the clearly exhausted president boarded the sidewheel steamer River Queen, docked on the Potomac, on March 22 with several aides, his wife, and young son Tad. It was an overnight trip down Chesapeake Bay, around Newport News, and up the James.

1862 New York Times map showing the James River from City Point to Richmond (Source: rarenewspapers.com)

At City Point, Lincoln was treated to a constant round of regimental lunches, dinners, and dances. He witnessed maneuvers against a last line of Confederates, reviewed two companies of troops, and spent five hours one day in the tents of the extensive City Point field hospital visiting each patient, sitting with the severely wounded, and shaking hands with hospitalized Southerners.

Grant set his troops moving west on March 29, soon cutting Lee’s last supply line by capturing the town of Petersburg. There Lincoln and Grant met for one final conference regarding the general’s plans to wrap up the war. Lee’s army bolted west from Richmond on April 2, leaving its warehouse district in flames. Jefferson Davis and what was left of his government fled on the last train south.

“Thank God I have lived to see this,” Lincoln told Admiral David Porter. “I have been dreaming a horrid dream for four years, and now the nightmare is gone. I want to see Richmond.”

A Hard Trip Upriver

Union troops entered Richmond April 3, telegraphing the news to City Point. By then, Grant was after Lee, and Lincoln decided to visit the newly captured city. A day earlier, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had telegraphed his dismay at the risk he said Lincoln had taken meeting with Grant in Petersburg. Lincoln likely grinned at the thought of the no-nonsense Stanton reading his wired reply: “It is certain Richmond is in our hands, and I think I will go there tomorrow. I will take care of myself.”

A view of the ruins in Richmond, Virginia (Source: Library of Congress)

A large escort including a detachment of Marines set out the morning of April 4 on Admiral Porter’s flagship, USS Malvern, in convoy with the fast gunboat, Bat. But plans for the flotilla’s grand arrival at the Richmond landing soon, so to speak, sank. Nearing the city, the James was clogged with the hulks of submerged boats and other debris, including dead horses. The Malvern and Bat could not fit through the obstacles. A tugboat was commandeered to pull a barge crewed by 12 Marines launched for the official party, reduced now to the president, Tad Lincoln (who turned 12 that day), and Admiral Porter.

Their progress was halted again when, to Lincoln’s obvious amusement, the tug ran aground. “It is well to be humble,” he told Porter as their trip continued, the Marines now rowing the barge the rest of the way.

A Long Walk Through a Defeated City

Finally reaching the Richmond landing, Porter was dismayed to find no one there to meet them. The city’s Union commander, General Godfrey Weitzel, apparently had no idea the president would arrive so promptly. According to historian Shelby Foote, who provides an extensive account of that day, the Virginia capitol building was visible through a haze of smoke on a hilltop two miles away. And so, surrounded by ten Marines armed with carbines (leaving two guarding the barge), the president, Tad, holding his father’s hand, and Admiral Porter began to walk.

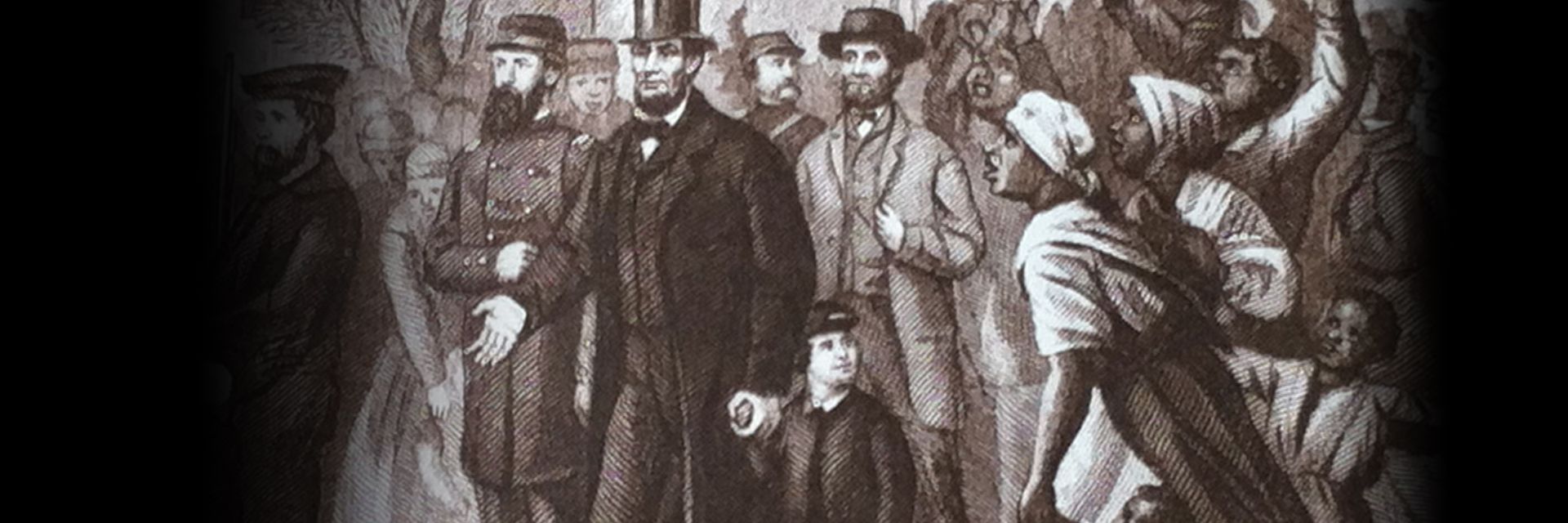

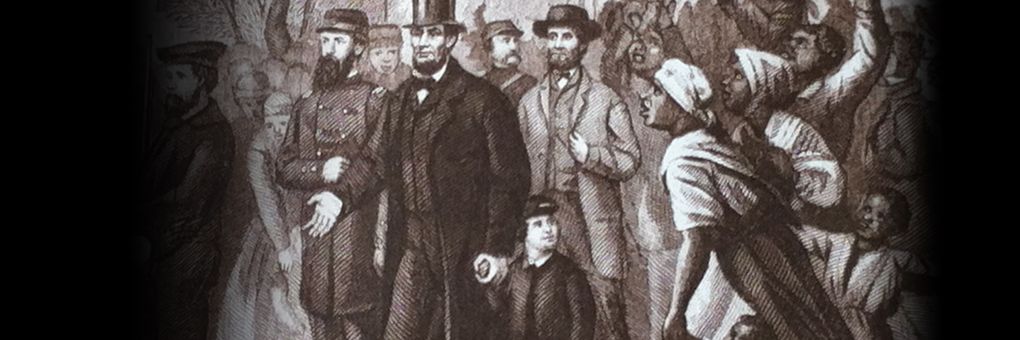

An artist’s rendering of Lincoln walking through Richmond (Source: Library of Congress)

Lincoln’s careworn face, long black coat, and stovepipe hat were recognized almost immediately by a group of former slaves then beginning their second day of freedom. History records their reaction as jubilant, loudly praising God. “Bless the Lord,” one old man reportedly cried upon seeing Lincoln, kneeling before the man who had liberated them. “The great Messiah. He’s been in my heart four long years. Glory, hallelujah!”

“Don’t kneel to me. That is not right,” an embarrassed Lincoln told them. “You must kneel to God only, and thank Him for the liberty you will enjoy hereafter.”

Word now traveled much faster than the presidential party, a growing crowd of former slaves following them. A Marine later recalled that once the procession reached the residential part of town, it had the attention of hundreds of Richmond’s white citizens. “Wherever it was possible for a human being to gain a foothold there was some man or woman or boy” watching them. “But it was a silent crowd. There was something oppressive in those thousands of watchers, without a sound of welcome or hatred.” Lincoln’s face, he remembered, “had the calm in it that comes over the face of a brave man when he is ready for whatever may come.”

The Confederate White House today (Credit: virginia.gov)

The unlikely procession made its way another half hour before it encountered an astonished Union cavalryman. “Is that old Abe?” he asked a nearly frantic Admiral Porter, who ordered him to gather a horse troop to escort them to Army headquarters, located at the Confederate White House, Jefferson Davis’s vacated dwelling, near Virginia’s Capitol. With ample protection at last, the presidential party reached its goal.

Resting at Jefferson Davis’s Abandoned Home

Hot and sweaty from his walk, Lincoln entered the study his foe had fled two days earlier and, settling into a chair behind the Rebel president’s desk, called for a glass of water. Now refreshed, he asked a housekeeper (quite possibly the Union spy Mary Bowser) to give him a tour of the Davis residence. As that was taking place, General Weitzel finally appeared.

After lunch with attending officers, Lincoln met with the only representative of the Confederate government in Richmond, Assistant Secretary of War John Campbell, who had resigned from the U.S. Supreme Court to serve the Confederacy. The two discussed ways in which Virginia might be readmitted to the Union. Putting off a longer meeting until the next day, the president set out for a carriage tour of the city with General Weitzel. A waiting crowd of black and white citizens cheered as Lincoln left the building.

The general asked if Lincoln had any orders for him regarding the treatment of defeated Virginians. Lincoln said he did not, and that “if I were in your place I’d let ’em up easy.” He repeated, “Let ’em up easy.”

By now, the Malvern’s sailors had cleared the way to the Richmond docks, announcing their arrival with a cannon salute. After an early dinner, Porter insisted the president spend the night aboard the ship, which Lincoln agreed to do. An armed guard was posted at his door. That night, two men were apprehended trying to board, claiming to have messages for Lincoln. A Confederate soldier had told Army officers that the president needed to take greater care if he left the boat again. Lincoln disregarded the warning. “I cannot bring myself to believe that any human being lives who would do me any harm,” he said. Nevertheless, he remained on the Malvern the next day.

As Lincoln slept, the city of Washington was in a delirious, all-night celebration of Richmond’s capture, and the imminent end of the war.

After a quiet night, Lincoln had a morning meeting with a delegation of Virginia officials to discuss ways to restore the state government. He agreed to allow legislators who had voted for secession to participate in “measures to withdraw the Virginia troops … from resistance to the general government,” later telling General Weitzel to offer the Southerners protection so long as they did not “attempt some action hostile to the United States.”

A Request for Dixie

Lincoln was back at City Point on April 6. There, an aide noted, “His whole appearance … had marvelously changed. That indescribable sadness … had been suddenly changed for an equally indescribable expression of serene joy.”

The steamer River Queen (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

He wanted to stay at the Army encampment, where he read regular updates from his generals chasing the Army of Northern Virginia, until Lee surrendered. “Let the thing be pressed,” he telegraphed Grant. But business had piled up at the White House during his two-week vacation, while Lee’s army kept slipping away from Union forces. He resolved to return to Washington.

On April 8, Lincoln boarded the River Queen for the trip home. At the departure ceremony, he asked the military band to honor a visiting French dignitary by playing the Marseillaise. He then requested to hear Dixie (something he would do again the following night in Washington).

“That tune is now Federal property,” he told his surprised listeners. He said he wanted “to show the rebels that, with us in power, they will be free to hear it again.”

The next day, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. Six days after that, Lincoln’s journey ended after he was carried mortally wounded to a small bedroom in a row house across the street from Ford’s Theater. As he died, "a look of unspeakable peace came upon his worn features," recalled his secretary, John Hay.

Ω

Title Image: Abraham Lincoln entering Richmond (April 1865) (Credit: Hollis, Huttre, Russell & Co., Boston, via Wikimedia Commons)