Recent reports of orcas attacking boats remind us that the name “killer whale” was earned, not given.

◊

Imagine spending 50 years in prison. Now imagine that your cell is just four times the length of your body. Every day for decades, you pace in circles waiting for someone to demand you jump on command or wave to an audience watching your every move. This might sound like a dystopian nightmare, but for Lolita the killer whale, it was reality.

On August 8, 1970, during an infamous round-up in Penn Cove on the Salish Sea, the soon-to-be celebrity cetacean was captured at the age of four and taken to the Seaquarium in Florida. Some killer whales escaped the nets that day, but dozens of orcas, some over 12,000 pounds, were hoisted from the sea in canvas slings to be distributed in padded containers to aquariums and marine centers nationwide. Two years later, Lolita and her fellow captives would have been protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act and likely would have spent their lives in freedom.

While Lolita was not lucky enough to escape the onslaught of nets, helicopters, and firecrackers that whale catchers used to round up her pod, she did fare better than many others. Entanglement in the nets caused many whales to drown, and others were struck by boats and suffered from traumatic injury. Her five decades in captivity were far longer than the average lifespan for wild-caught whales taken into captivity, who often suffer from dorsal fin collapse, blindness, and/or heightened aggression leading to deadly fights.

But aggression in killer whales is not isolated just to those in captivity. Scientists have observed increased numbers of aggressive interactions between orcas and boats in the last five years, particularly in the Strait of Gibraltar. And recent news reports point to incidents in which several vessels were sunk as a result of what seemed to be orchestrated attacks by orcas.

For more on whales, check out the MagellanTV series Titans of the Deep.

Human & Whale Interactions

Between a featured appearance in the Old Testament in the story of Jonah and an iconic role in American literature in the form of Moby Dick, whales have earned a unique place in the stories that humans tell. In sailor lore, they were often demonized as mythical sea monsters whose likeness would be fantastically imagined in drawings of fanged creatures on maps. But in our current era of steel ships, submarines, and sonar, engineering has given humans an advantage over cetaceans, and the tide has changed regarding who ought to be afraid of whom.

An orca attack on a 43-foot boat in the Pacific Ocean left a British family stranded for 38 days. Their story of survival in a dinghy eating turtle was turned into both a book and movie called Survive the Savage Sea.

Shipping traffic chops through the oceans at all hours of the day. Consequently, the dozens of species of whales that share the waters are vulnerable to human-produced sounds and spills – and even the occasional collision. For the North Atlantic right whale, an endangered species, collision with ships and entanglement with fishing gear were recorded as the primary cause of death among the bodies that scientists were able to study. Whales’ migration and breeding routes now criss-cross with shipping routes, and any deviations by either party can result in a tragic encounter.

How We’re Impacting Whales

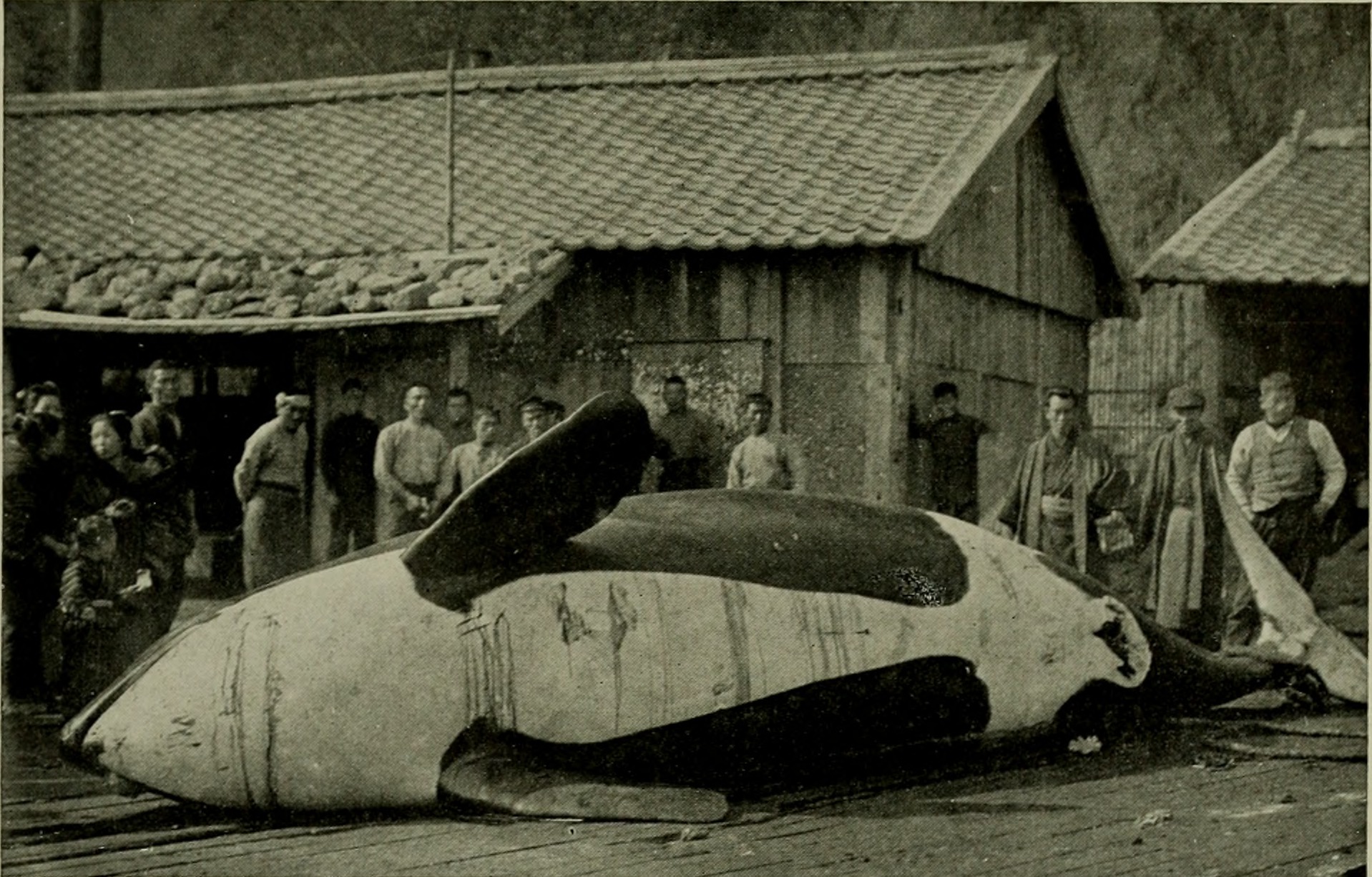

Even before whales became desirable as amusement park attractions, commercial whaling had been around for centuries, and the use of whale bones and blubber dates back millennia. At the height of the whaling industry, sailors would fling harpoons into the water in hope of drawing back the massive mammals to be butchered. Whales’ bodies provided oil for lamps and industrial machinery; bones for corsets, hoop skirts, and adornments such as scrimshaw; and meat for pet food and even human consumption. Once humans created boats and weaponry to hunt them more efficiently, whales stood out as prized and very profitable prey.

Killer whale secured for the American Museum of Natural History (Source: Internet Archive Book Images, via Wikimedia Commons)

In recent years, despite international agreements that restrict and ban commercial whale hunting, the human impact on whales is still present. Sonar waves sent through the depths by naval ships and submarines saturate the seas with noise pollution. The cacophony can interfere with whales’ calls and how they coordinate attacks on their prey. Increased boat traffic, plastic pollution, and oil spills expose orcas to more toxins and unfamiliar sights and sounds than ever before. Killer whales have also been entangled in fishing lines and nets.

While seeing a whale from a boat is a welcome sight for humans and has become a huge industry for boating tourism, a whale who sees a boat might not harbor the same sentiments. In whale culture, the presence of boats could signal danger from nearby nets or bring along concussive noise – or worse, as was the case for Lolita’s siblings and cousins. In just the course of a few centuries which coincided with an increased human presence on the sea, whale populations went into steep decline. It’s not too much of a stretch to believe that whales might well have come to associate human activity with danger.

Have Killer Whales Become More Aggressive?

Over the course of just a few generations, whales have been subjected to new predators, threats to their homes, and forced separation of their pods. When researchers study their behaviors, they note that groups of whales, called pods, resemble the tight-knit family structure we recognize in human society. Evidence indicates that whales pass along songs and hunting techniques to their kin. While humans have yet to crack the code of whales’ phonetics, we know they adapt their communication to pass along messages about familiar affiliations, food, and impending dangers.

Toothed whale species tend to sing songs composed of clicks and whistles, whereas whales with only baleen, a keratin tissue that filters krill, use deep tonal sounds in their remarkable songs.

Since 2020, there have been 500 recorded instances of whales making contact with vessels in the waters near where the Atlantic Ocean intersects with the Mediterranean Sea. In these encounters, dozens of ships have been damaged and three have been struck to the point of sinking. When whales approach, some boaters have recorded behaviors of ramming the rudder, slamming against the hull, and one group even tactically jolting the boat from two angles at once to make it flip. The recent incidents have caused a stir among scientists, yachtsmen, and orca advocates alike.

Orca performance at Vancouver Aquarium, 1981 (Source: SoftwareSimian, via Wikimedia Commons)

Some hypothesize that the recent sinkings off the coast of Gibraltar might have been done by a single pod with a vendetta against humans. In fact, an orca named Gladis White by researchers has been identified as one of the attackers. She might have undergone a traumatic encounter, and in response adopted an aggressive attitude toward boats. Within her pod of 40, it is possible that Gladis has been disseminating tactics on attacking boats as a form of retribution.

But other scientists think the behavior is being misinterpreted. Instead, they theorize that the orcas perceive boats as a sort of toy, with rudders making for solid surfaces to scratch up against and propellers offering a pleasant sensation on their faces.

Sympathizing with Both Sides

Or course, the truth is that we don’t know what is happening and why this concentrated behavior in a select group of killer whales in the Atlantic has arisen. We likely never will. What is clear, though, is that 2023 marks an interesting moment for whales in the eyes of humans. On one side we still see orcas as a poster child for certain environmental justice movements opposing the maltreatment of animals in captivity. On the other hand, we are reminded that killer whales are aptly named apex predators whom, thanks to their performances as tamed marine park attractions, we might be severely underestimating. Should our efforts be spent protecting whales from humans, or vice versa?

An orca and sail boat encounter (Source: Pixabay)

An orca and sail boat encounter (Source: Pixabay)

In a cultural moment deemed “the age of trauma,” it is telling that scientists are pointing to this word as a potential explanation for the orcas’ behavior. When you hear or read first-hand accounts by experienced skippers passing through waters they’ve navigated for decades, you can sense and even empathize with their fear and alarm. But when you contextualize the situation from the whale’s perspective, and imagine their trauma, fear, and the rapid changes in their experience over a short span of time, you might be able to empathize with the whales in the same way you can with the human witnesses.

CALLOUT: The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was established fewer than 80 years ago. An orca can live up to about 90 years in the wild. So, there may well be orcas in the wild today who are older than the IWC.

Encounters No One Wants

Accounts from sailors aboard some of the targeted yachts speak to the fear that ran through them as their vessels were systematically assaulted for about an hour. There’s no denying how terrifying it must be to be aboard a small assemblage of steel, wood, and fiberglass that is subject to such an attack. That these incidents might become more common could very well make you think twice about an afternoon sail in regions such as the waters off the Iberian peninsula where attacks have occurred.

The Atlantic Orca Working Group, or GTOA per its name in Spanish, is a research group based off the Iberian peninsula that has been tracking orca and vessel interactions for years. Based on their findings, the group advises boaters to stop their engines, lower their sails, and to move away from the boat’s rudder wheel as well as any sharp objects and edges. The advisors acknowledge that only half of vessels that interact with orcas experience damage, and even then it is typically isolated to the rudder. But the threat to people on a boat is very real, so taking precautions is paramount when sailing in the area.

An Unknown Future

For some cultures, whales are seen as symbols of family and luck. Within whale culture, family is at the core of identity, and luck plays a big role in how their lives play out. Getting entangled in a net or needing to breathe at the wrong time along a major shipping route might change a whale’s life and its pod’s forever.

Two orcas surfacing (Credit: Robert Pittman, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Native American Lummi Nation, based around the Puget Sound area, calls whales “qwe lhol mechen” which translates as “our relatives under the water.” Advocates for returning Lolita, also called Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, to her home waters nearly exhausted the legal arguments, but in early 2023 they prevailed. She is set to be returned to the Pacific Northwest within the next two years, after which she will be closely monitored in the wild. Though her body and behavior might be unrecognizable to her old pod, scientists are confident that thanks to their complex social patterns, her family will take her back.

After the news of the recent attacks, it’s hard not to wonder if Lolita, a whale taken from her home who most certainly experienced trauma, will exhibit signs of aggression when reunited with her family. While some advocates are proposing ideas that would restore habitats and give whales space to live their lives without having to adapt to oil tanker routes or aquarium demands, it is also clear that whale and human lives are to some degree inextricably entangled. It is crucial to recognize the role that each of our species play in inciting fear and alleviating obstacles in the other’s lives.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. She also writes for Local Life magazine. Originally from Georgia, she attended college to study philosophy and studio art. She now works in Chicago as a media relations coordinator.

Title Image: Orcas glide by whale-watching boat (Source: Pixabay)