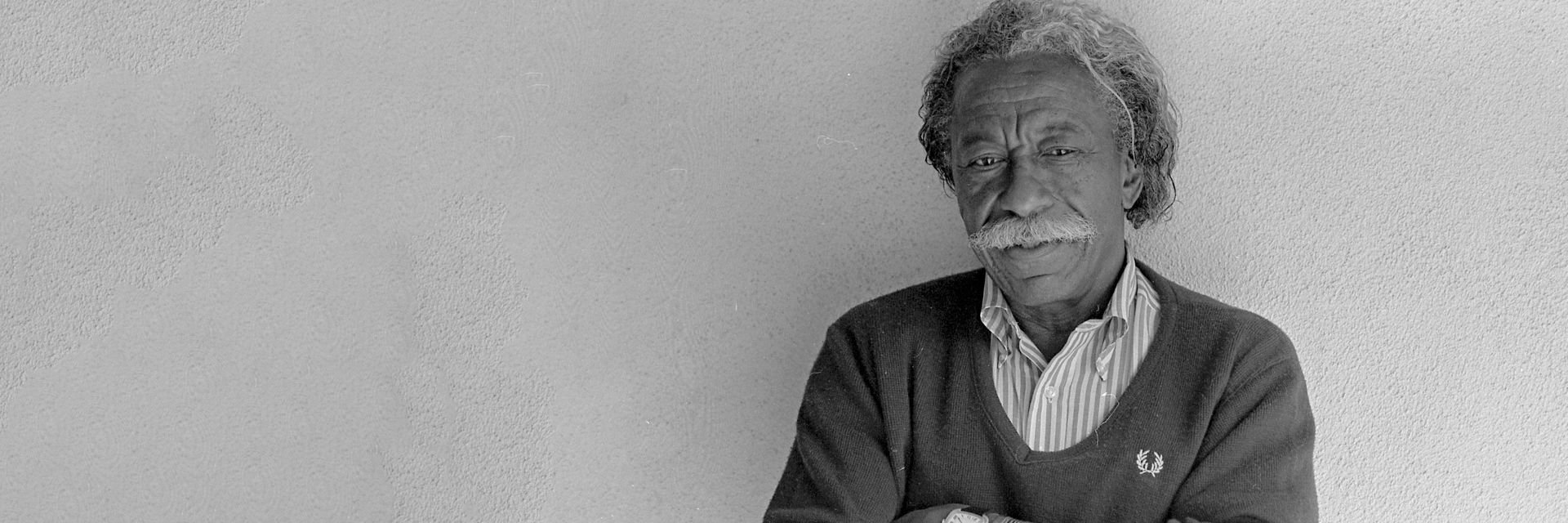

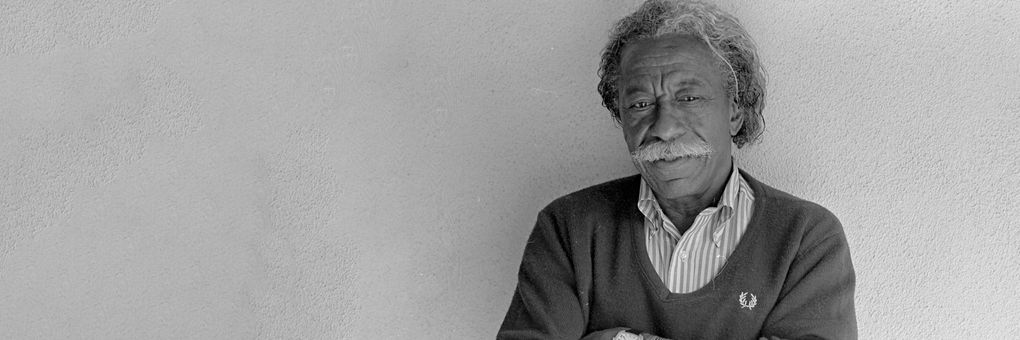

Gordon Parks’s artistic output – in photography, film, literature, music, and more – shows him to be, above all, a humanist.

◊

Gordon Parks was talented in many artistic fields, but to call him merely “talented” feels woefully inadequate. Across a career that spanned photography, filmmaking, writing, and music, Parks built a legacy that defied categorization. He was not just a trailblazer in one discipline but a master in several, achieving feats that would be extraordinary even if taken separately. Perhaps “genius” is more apt.

Beginning his professional career as a fashion photographer for Vogue magazine, he revitalized the art by adding motion and personality to the models he portrayed. He then became the first Black staff photographer at Life magazine, capturing the dignity and resilience of his subjects with an unflinching eye. As a filmmaker, he broke barriers in 1969 by directing The Learning Tree – the first major studio film directed by a Black filmmaker – and redefined cultural cool with Shaft, one of several films that launched the blaxploitation genre. Beyond the camera, Parks authored novels, memoirs, and poetry, composed music, and left an indelible mark on American culture.

What unified Parks’s kaleidoscopic body of work was his deep and abiding humanism. Whether photographing a Harlem gang leader, a Parisian model, or a rural Kansas family, Parks sought to reveal the complexity and shared humanity of his subjects. His art was not merely a reflection of his era’s struggles and triumphs but also a call for empathy, justice, and understanding. Through the lens of his camera and the breadth of his storytelling, Parks chronicled the inequalities and joys of life with equal passion, ensuring that voices too often ignored found a place in the American consciousness.

Parks was a creator whose work transcended boundaries and disciplines, rooted in the belief that art has the power to challenge, inspire, and heal. Parks’s wide-ranging achievements and enduring humanism made him one of the most compelling and essential creative figures of the 20th century – a man whose work continues to resonate and whose life serves as a testament to the transformative power of art.

Learn more about Gordon Parks and his friendships with Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X in this engrossing MagellanTV documentary.

Striving for Greatness: Parks’s Initial Years as a Photographer

Gordon Parks’s journey as an artist began with a stroke of fate and an eye for detail. In 1937, during the height of the Great Depression, Parks stumbled upon a used camera in a pawnshop and decided to try his hand at photography. Armed with little more than intuition and a natural talent for composition, he began photographing his surroundings. His early work – portraits of friends, family, and the overlooked moments of daily life – revealed a deep sensitivity to light, shadow, and the emotional essence of his subjects.

Parks’s ability to capture beauty in the mundane caught the attention of local patrons, eventually earning him a fellowship with the Farm Security Administration in 1942. It was here that Parks honed his craft and began developing the visual language that would define his career.

One iconic photograph from this period, American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942), is emblematic of his trailblazing artistry. In the image, Ella Watson, an African American cleaning woman, stands solemnly in front of an American flag, posed between a mop and broom. The photo was a searing indictment of racial and economic inequality, a stark reimagining of Grant Wood’s classic painting, American Gothic. This image and others like it marked Parks as a photographer unafraid to confront systemic injustice, using his camera as a weapon against prejudice.

American Gothic, Washington, D.C., by Gordon Parks, 1942 (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

American Gothic, Washington, D.C., by Gordon Parks, 1942 (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the later 1940s, Parks transitioned into fashion photography, a move that was revolutionary for its time. Breaking into an industry dominated by white photographers, Parks became one of the first Black photographers to work with prestigious publications like Vogue and Glamour. His fashion photography was more than a showcase of elegance; it was a political act. Parks relished showing his models captured in mid-action, bringing life to still images. In this way, he advanced fashion photography from a static presentation of the sculptural beauty of models in dresses to envisioning models as real people, catching them in movement outdoors, and showing high fashion as a part of real life.

Parks also focused on his models’ sophistication and dignity, particularly when working with Black women. By placing Black beauty front and center in the pages of high-profile magazines, he challenged the narrow, Eurocentric standards of the fashion world. His work elevated his subjects, making them visible in a society that often erased them.

In 1948, Parks achieved another historic milestone by joining the staff of Life magazine, becoming the publication’s first African American staff photographer. This was no small feat in a segregated America, where the doors to elite institutions were rarely opened to Black artists. At Life, Parks solidified his reputation as a master storyteller, producing photo essays that illuminated the struggles and triumphs of ordinary people. From chronicling gang life in Harlem to capturing the devastating effects of poverty in Brazil, Parks’s work at Life balanced artistry with activism. His photographs didn’t just document – they humanized, creating a visceral connection between his subjects and viewers.

Parks befriended Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay) when they met for a 1966 Life cover story illustrated with his photographs of the boxer. In 1970, his essay for Life, “The Redemption of a Champion,” documented Ali’s comeback after his ban from boxing. Parks presented Ali as a multifaceted figure of strength and defiance.

Parks’s early career as a photographer was groundbreaking not only because of his technical skill but because of the barriers he shattered along the way. As a Black artist operating in predominantly White spaces, he had to navigate a world that was often hostile to his presence. Yet Parks didn’t just succeed – he excelled, using his work to challenge stereotypes and broaden the cultural narrative. His early achievements laid the foundation for a career that would continually redefine what art could achieve, proving that creativity, when coupled with courage, could be a powerful force for change.

Injecting Cinematic Stories with Humanistic Detail

Gordon Parks’s transition from photography to filmmaking was as bold and groundbreaking as the rest of his career. By the late 1960s, Parks had already established himself as a master visual storyteller through his still photography, but his ambition to tell stories on a larger canvas led him to the world of film. His debut feature, The Learning Tree, was a deeply personal project. Parks wrote, produced, and directed the adaptation of his semi-autobiographical novel, investing the film with a rich sense of authenticity and humanity that reflected his own experiences growing up in Kansas.

Promotional film poster for Gordon Parks’s The Learning Tree (Source:IMP Awards, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Learning Tree’s tender portrayal of familial bonds, its exploration of systemic racism, and its nuanced depiction of a young man’s internal struggles were groundbreaking at a time when Black characters were often relegated to one-dimensional roles in Hollywood. Parks’s directorial approach, honed through years of composing striking images as a photographer, brought a painterly quality to the film, while his attention to detail created a narrative that felt both intimate and universal.

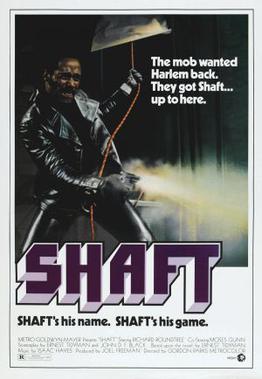

The Learning Tree firmly established Parks as a filmmaker capable of bringing an authentic Black perspective to the screen. This authenticity would take a very different form in his next feature film, Shaft (1971), a genre-defining hit that helped launch the blaxploitation era. Unlike the reflective tone of The Learning Tree, Shaft was gritty, stylish, and full of unapologetic bravado. Parks directed the film with a sharp eye for action and a deep understanding of what Black audiences had long been missing in Hollywood: a hero who was both fearless and unbowed by systemic oppression.

_1973.jpg)

Film poster for Shaft (left); actor Richard Roundtree in character as John Shaft. (Sources: Poster, via Wikipedia; Roundtree photo, MGM, via Wikimedia Commons)

The story of John Shaft, a suave private detective navigating Harlem’s underworld, was revolutionary not only because it placed a Black protagonist at the center of the action but because it celebrated Black masculinity in a way that was rarely seen in mainstream cinema. Parks infused Shaft with an authenticity rooted in his own experiences, creating a world that felt real and lived in. His direction emphasized the cityscape as a character in itself, capturing the urban grit and vitality of New York City in the early 1970s.

While some critics later questioned the blaxploitation genre’s reliance on stereotypes and its potential to exploit Black culture for commercial gain, Shaft stood apart as a film that celebrated Black identity while breaking new ground in Hollywood. For his part, Parks actively resisted the term “blaxploitation.” In an interview published in The Village Voice in 1976, he firmly stated, “I don’t make black exploitation films.”

Gordon Parks’s foray into filmmaking wasn’t just a career pivot – it was a declaration of his belief in the power of storytelling to reshape perceptions and inspire change. Whether drawing from his own life or elevating a new kind of Black hero, Parks used the medium of film to amplify voices and stories that had long been silenced. His legacy as a filmmaker is not only a testament to his creative genius but also to his unwavering dedication to portraying the full spectrum of Black humanity with dignity and depth.

British television host Reggie Yates examines the rise of Black themes in American media in TV's Black Renaissance.

Achievements in Other Artistic Forms Displays Parks’s Humanistic Philosophy

Gordon Parks’s artistry extended far beyond photography and film, encompassing literature and music composition, where his deep humanism continued to shine. As a writer, Parks authored several autobiographical works, including A Choice of Weapons (1966) and Voices in the Mirror (1990), which chronicled his journey from poverty to world renown. Parks also wrote poetry and novels, often exploring themes of racial injustice, personal struggle, and the beauty of everyday life, all while drawing on his own experiences to connect with readers on a deeply personal level.

A portrait of Gordon Parks with piano in background by photographer David Finn (Source: National Gallery of Art Library, via Wikimedia Commons)

A portrait of Gordon Parks with piano in background by photographer David Finn (Source: National Gallery of Art Library, via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to his achievements in other arts, Parks was a gifted composer, creating music that reflected his emotional depth and cultural roots. He composed scores for his films, including The Learning Tree, and wrote orchestral works such as Concerto for Piano and Orchestra and Tree Symphony. His music, much like his photography and writing, carried a profound sense of empathy, often evoking themes of struggle and triumph.

Gordon Parks’s Humanism Defines His Creative Output in Many Fields

Across all these media, from photography and film to music, prose, and poetry, Parks’s humanism remains central. Whether through a poignant memoir, a haunting musical composition, or an evocative photograph, Parks sought to capture the essence of humanity – its pain, its beauty, and its unyielding hope. His diverse body of work reveals an artist deeply committed to using every tool at his disposal to foster understanding and compassion in an often-divided world.

Parks demonstrated an unwavering dedication to portraying the richness and complexity of human life. Whether through the defiance in Ella Watson’s gaze, the stirring words of his memoirs, the fierce pride and self-confidence of the title character in Shaft, or the evocative strains of his music, his art, at its core, was a celebration of humanity in all its forms – a call to recognize the struggles and triumphs that connect us all.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer and Associate Editor for MagellanTV. A journalist and communications specialist for many years, he writes on various topics, including Art and Culture, Current History, and Space and Astronomy. He is the co-editor of My Body Is Paper: Stories and Poems by Gil Cuadros (City Lights) and resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Portrait of Gordon Parks (background edited) (Credit: Iris Schneider, Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection at the UCLA Library, via Wikimedia Commons)