Not everyone who arrived on Ellis Island made it across the harbor to New York City. If immigrants failed to pass health inspections, they would be sent to one of several hospitals, where they would often languish for years before being cleared to enter the United States – if they were lucky. The hospitals are abandoned today, but they are windows into a forgotten aspect of a remarkable chapter of America’s past.

◊

Imagine saving up for months or years, dreaming of escaping your tiny hometown in order to make it in America. Imagine packing up your life, making the long trek across the ocean, and making it to the end of an endless line that’s supposed to lead you out to the glittering city beyond – only to be stopped, inspected, quarantined, and sent back to the place you hoped to leave behind.

That was the experience of many of the immigrants who stayed in Ellis Island’s Immigrant Hospital, a building that today languishes in disrepair. Walk through its halls, though, and you can almost hear the echoing sobs of those immigrants, their broken dreams still haunting its dilapidated bedrooms and eerie halls.

I visited the hospital in 2017 as part of a hard-hat tour held by the Save Ellis Island Foundation, which allows the public to see the hospital in small, tightly supervised groups. Since then, I’ve been unable to get it out of my mind. Most of the windows were broken, with vines growing through them and spilling out onto the floors. Sparrows floated through the rafters, and everywhere, I saw peeling paint and the sparse remnants of decaying furniture.

Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital - Island 3 Exterior. (Image Credit Z22 via Wikimedia Commons)

Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital - Island 3 Exterior. (Image Credit Z22 via Wikimedia Commons)

There was something deeply haunting about it. Here was a building that is a testament to decaying and broken American dreams, full of the ghosts of the many who have wanted to come here but who were turned away.

It’s easy to forget how rampant sickness and disease were back then, and how tenuous the American Dream has always been. But in those buildings, that history felt more alive and more relevant than ever.

The American Dream Lottery

In 1922, my great grandfather arrived in the U.S. at the age of 19, fresh from Germany and speaking not a word of English. He sailed through Ellis Island and worked as a hot dog salesman at Coney Island before he entered the window washing business, riding up and down New York’s skyscrapers. Eventually, he converted from Judaism to Christianity, went on to get his PhD at New York University, and wrote an influential textbook on the real estate industry.

In short, he won the American Dream lottery. But he very easily might not have been that lucky. A year before my great grandfather arrived on Ellis Island, a 19-year-old Australian salesman named Ormond Joseph McDermott arrived there in the shadow of Lady Liberty. He had planned to travel to Indiana, where he would learn the “motor car” business at the Studebaker factory. But he left his passport on the ship, and so was quarantined in a dormitory, where he caught scarlet fever. He was moved to the island’s Contagious Disease Hospital, where he died six days later.

A forgotten passport changed the trajectory of McDermott’s life, cutting short his own existence as well as the existence of any future descendants. While my great grandfather went on to marry and have children who would eventually lead to me, McDermott – like so many others – lost his chance in that hospital.

Learn more about the fascinating history of Ellis Island in the documentary Ellis Island: A History of the American Dream.

His story is only remembered because of archival work done by Lorie Conway, who came across his doctor’s report while researching the island’s history for a documentary, book, and website called Forgotten Ellis Island. According to Conway, many patients’ records are missing, and with them, the people they represent. Instead, they live on only as stories and memories, passed through generations, becoming more mythic with each retelling before they slip away.

The Statue of Liberty (Image Credit: Elli Buzz via Pixabay)

The Statue of Liberty (Image Credit: Elli Buzz via Pixabay)

From 1892 to 1954, over 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island. Over the course of Ellis Island’s operation, tens of thousands of immigrants would pass through the 22 buildings that formed the island’s hospital complex.

Every passenger was screened for health issues when they arrived on American shores. “The name of the game here is you had to...be an able bodied citizen,” said Brett Moyer, a tour guide with Save Ellis Island. America’s arms might have been open to the tired and the poor, but the nation would not accept anyone with any sign of illness onto its shores.

Ellis Island Health Screens Make Or Break Immigrants’ Chances

Health screenings began as soon as passengers arrived on the island. When immigrants disembarked from the ferry to Ellis Island, they were told to carry their bags up a long flight of steps. Anyone who stopped to catch their breath was pulled aside and examined for heart disease, fever, and lung problems.

Immigrants were also watched as they carried their bags through the Great Hall, where a physician scoured the ranks for abnormalities like a limp or a goiter. From there, doctors examined every immigrant individually, checking their vision and breathing and paying close attention to their hair, scalp, and skin for any diseases or signs of infections. Anyone who behaved oddly was noted for “psychopathic” tendencies.

The last part of the health inspection was an examination of the eyelids, which doctors would check for any evidence of trachoma. Today trachoma is treated with antibiotics, but back then it was a deadly disease that could cause blindness, and it caused many would-be immigrants to be sent home.

“Sick children age 12 or older were sent back to Europe alone and were released in the port from which they had come. Children younger than 12 had to be accompanied by a parent.” —OhRanger.com

Less than one percent of immigrants were rejected for health reasons, but that means about 120,000 people were sent back, and thousands more languished in the hospitals for long periods of time.

Unfortunately, not everyone was given an equal chance at entering America. “The Island’s screening routines created dehumanized, impersonal, and industrial spatial regimes of circulation that allowed unhealthy and undesirable working-class immigrant bodies to be identified and segregated from the healthy and desirable ones,” writes Guillermo Sánchez Arsuaga.

Immigrants from groups considered “non-white” at the time, like Mediterraneans, Italians, or Eastern European Jews, were more likely to be profiled as contagious or feeble-minded, partly thanks to prevailing beliefs rooted in eugenics or racism.

For example, the 1924 Immigration Restriction Act was designed to halt flows of “dysgenic” Italians and European Jews. Upon signing the act, President Calvin Coolidge proclaimed, “America must remain American,” and it’s not hard to trace a throughline of xenophobia all the way to today.

Inside the Hospitals

If you were singled out on Ellis Island as being in need of medical care, you could be sent to a few different places. People sent to the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital had a relatively good chance of making it out, as they had a condition that was most likely curable.

Those sent to the Contagious and Infectious Diseases Hospital, however, knew that they had very little chance of ever making it all the way to America. The hospital complex was separated from the rest of the island by a strip of water, partly because the prevailing medical wisdom at the time was that germs could not pass over water.

The hospital was separated into pavilions, each dedicated to different infectious diseases. It boasted a total of eight measles pavilions as well as buildings dedicated to cholera, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and other diseases of the era.

Nurses lived directly above the patients, and the top two medical officers on the island lived with their families in buildings attached to the hospital. Despite this proximity, sanitary measures appear to have worked. A laundry room churned out 3,000 pieces of clean laundry each day, and a machine called the “mattress autoclave” boiled mattresses to rid them of bacteria. Though around 3,500 patients died in the hospital during its half-century of operation, there is no record of nurses or staff contracting any illnesses.

The hospital also had an eight-cadaver refrigerator (which was ominously located inside the operating room), an autopsy amphitheatre, and a courtroom where a board would decide patients’ fate.

It might be difficult to believe, but the Infectious Diseases hospital wasn’t the worst place on the island. If you were taken to the Psychopathic Pavilion, you knew that you would never have a chance of living free in the United States of America.

.jpg)

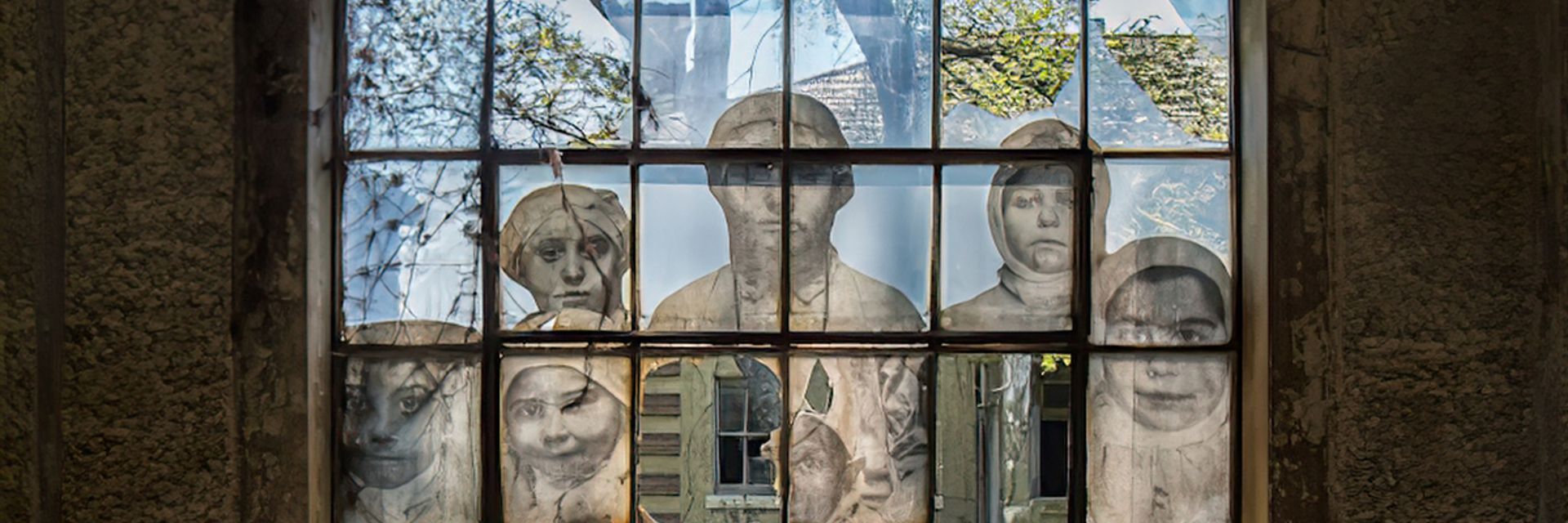

Old photos of immigrants superimposed onto a building in the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital.

(Image Credit: JR, via Rhododendrites on Wikimedia Commons)

The ward typically housed 20–30 patients at a time, kept in prison-like conditions. Even today, the building’s sun porch is closed off by iron bars, and rooms still have cages over the doors, windows, and even some of the furniture.

The state of mental health care in the early 20th century was not ideal, to say the least. Federal immigration laws proclaimed that “idiots, imbeciles, epileptics, the feeble-minded, [and] insane” should all be sent home, so the Psychopathic Ward was a particularly devastating waystation for all those who passed through its doors.

“The Psychopathic Pavilion was designed to fulfill three functions: observe questionable cases, treat acute stress resulting from the hardships of the voyage, and house those slated for passage back to Europe… But what happened when nativism and changing immigration policies butted up against the murkier medical (or pseudo-medical) quandaries of personality, ‘feeblemindedness,’ intellectual capacity, cultural differences, and general foreignness?” — Annabelle S. Singerland, Hektoen International

Strangely enough, right next to the Psychopathic Ward was the Maternity Ward, where a total of 350 babies were delivered during the building’s lifespan.

Still, no matter which hospital you were sent to, the outlook was bleak – particularly for children. In a manner eerily reminiscent of the U.S. government’s actions at the Southern border today, many sick immigrant children were separated from their families, never to see them again. If their families could not afford the treatment at the hospital, the children would often be deported.

Ruins and Ghosts: The Hospitals Today

The hospitals of Ellis Island were shuttered in 1930 as immigration slowed, and they were abandoned in 1954. They remained derelict for many years, falling into greater and greater disrepair.

In 1999, the nonprofit Save Ellis Island began to work on reopening some of the buildings. Today, the organization runs tours that take visitors inside the hospitals, providing a unique window into a distinctive chapter of America’s past. The buildings are a reminder that the U.S. once prided itself on its status as a beacon for immigrants, and they also remind us that leaving home in search of a new land has never been easy.

Today, the hospital complexes have mostly been kept in a state of natural disrepair, with a few unique additions. In 2014, the artist JR hung a number of large black-and-white images of immigrants around the hospitals’ corridors. The installation, entitled “Unframed, Ellis Island,” is a tribute to the lost stories and fragile hopes and dreams of those who wandered the hospital’s halls.

.jpg) Ellis Island Hospital Window Mural. (Image Credit: JR, via Rhododendrites on Wikimedia Commons)

Ellis Island Hospital Window Mural. (Image Credit: JR, via Rhododendrites on Wikimedia Commons)

In one photo, pasted on a window that looks out over the Statue of Liberty, a group of children stare out at the viewer. Their heads are wrapped in white cloth; they were diagnosed with the scalp disease favus. Whether they made it into America is unknown. But it’s easy to imagine them standing transfixed by Lady Liberty’s outline over the glittering city skyline, eyes full of the dreams that have drawn so many to America only to be detained at the last moment.

Today, the photo is fading thanks to the sunlight and salty breezes. It is being reclaimed by nature like the rest of the hospital, worn away by time like so many of the anonymous figures who wandered the halls. Or do they still wander there? “I would feel almost human energy in these empty rooms,” JR said. “It is a perfect situation for a stuck soul.”

Ω

Title Image credit: Rhododendrites, via Wikimedia Commons