There was little hint that the young and timid Indian lawyer would become one of the greatest political leaders of the 20th century. But Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent Satyagraha movement, civil actions he developed by 1908 to combat the race prejudice he found in South Africa, still inspires millions.

◊

January 30, 2023, saw the 75th anniversary of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. He was revered in his lifetime, and for decades after his murder, for his dedication to nonviolent political action and a scrupulous adherence to homespun simplicity and conflict resolution. Decades after his death, however, Gandhi’s personal shortcomings and early racist attitudes received greater attention.

Gandhi had little respect for Blacks over his first decade in South Africa, and only gradually rejected racism as his political ideas matured. However, he spent no political capital in the cause of racial equality in the nation.

Though absolutely central to the formation of an independent India, his methods are now seen less as universally true and more as best suited to the particular social realities that characterized the end of the British Raj.

Gandhi was, in fact, a frustrated and disappointed political leader when he was killed by a Hindu extremist furious with his message of accommodation with India’s other religious subcultures – Muslim, Christian, and Buddhist. When Gandhi died in early 1948, younger political leaders, especially India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, were modernizing India. Gandhi’s archaic dream was to return the nation to an idealized pre-modern past, rejecting all new technologies in favor of a handmade, literally homespun, rural social order.

But if Gandhi’s political and personal shortcomings darkened his final years and contemporary reputation, he got a lot right. The political movement he initiated with truly radical notions of nonviolent political action still offers a template to contemporary agents of social change.

For more on Gandhi and the circumstances surrounding his death, check out the MagellanTV documentary Who Killed Gandhi?

Gandhi’s Diverse Cultural Background, and His Legal Studies in England

Gandhi, born Mohandas Karamchand, was the scion of a family of high-ranking civil servants in the small royal state of Porbandar, in the northwest coastal district of Kathiawar. A remarkable range of religious ideas infused its culture. Gandhi’s family belonged to a small sect that incorporated beliefs from Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, Jainism, and Judaism into a Hindu framework, one pacifist and strictly vegetarian.

The first inkling of Gandhi's destiny came in 1888 when the 18-year-old (married at 13 and already a father) left India to study British law in London, earning his degree in three years. Back in India, a fundamental timidity prevented him from cross-examining witnesses in court. He managed to eke out a living drafting legal petitions.

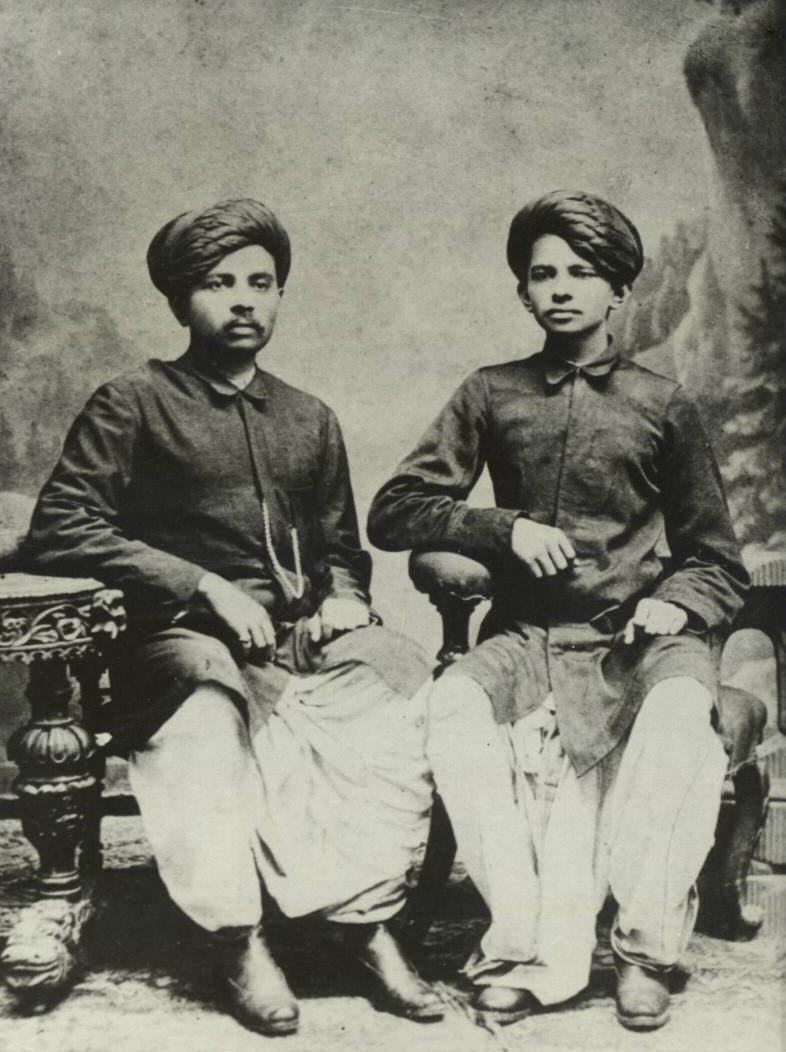

The 17-year-old Gandhi, at right, with his brother in 1886. (Source: Wikipedia)

His break came in 1893 when he was given a post in the firm of a distant cousin in Durban, South Africa, to help out in a lawsuit. Except for two brief visits to India, South Africa would be his home for the next 22 years.

Gandhi’s relatively high caste status, and being a law student in London, had mainly shielded him from race prejudice to that point. It was a different matter in South Africa, where the young lawyer was immediately subject to debasing treatment.

On his first rail trip to Pretoria he was told to ride in the baggage car, regardless of his first-class ticket. Refusing, he was put off the train and had to wait overnight in a station for a train the following day. Transferring to a stagecoach to Johannesburg, a guard told Gandhi to sit at the driver’s feet. When he refused, the guard began to beat him before being stopped by fellow passengers. On the final leg of his trip, he was again nearly forced from his first-class train seat, keeping his place only with the help of a fellow (white, of course) passenger.

The humiliations of his first days in South Africa were indelible experiences that forced the young lawyer to reconsider the status of Indians in the British Empire, and the role he was supposed to play in supporting the status quo.

The South African lawsuit was over in a year. But instead of returning home, Gandhi resolved to lead opposition to a bill intended to deny Indians the right to vote. Though eventually unsuccessful, the young lawyer was now considered a leader of South Africa’s Indian community, instrumental in founding the South African Indian Congress, a rights advocacy group, in 1894.

During the 1899–1902 Boer War, Gandhi organized an ambulance corps of 1,100 Indian men, whose religious beliefs forbade engaging in violent conflict, in support of British troops. The corps saw significant action carrying wounded over several miles of hard terrain at the vicious 1900 Battle of Spion Kop, for which Gandhi and over 30 of his countrymen received the Queen’s South Africa Medal for distinguished service.

Gandhi Leads A Radical New Movement Based on Traditional Beliefs

By the early 20th century Gandhi was a central player in the political and legal battles for Hindu civil rights in South Africa. As this political engagement grew, he formulated a philosophy of civic protest, one based on strict nonviolence and dedication to peaceful resolution of conflict.

Central to Gandhi’s political thought was the Hindu concept of Ahimsa, Sanskrit for complete harmlessness. Its philosophy extends to absolute nonviolence, a rejection of harm to any living being, and leading a life guided by vegetarianism. In 1906, he rejected all desire for wealth and any sexual activity outside the procreation of children. He began exercises in self-restraint based on the Hindu concept of Brahmacharya, Sanskrit for “pure conduct.”

By 1908, Gandhi had formulated his concept of what he called Satyagraha (a Hindi word meaning “holding onto truth”), his lasting moral philosophy meant to guide the political movement he now led.

Followers of Satyagraha rejected all violent thought and action, and promoted conflict resolution by way of the personal cultivation of peace and love. Satyagrahahis were dedicated to leading simple, morally upright lives dedicated to truth, and to working toward bringing compassionate, non-exploitive political and economic systems to worldwide acceptance.

In 1904, Gandhi established a vegetarian community of shared resources and living accommodations near Johannesburg that he called Phoenix Farm. It would be his headquarters for the next decade.

The first Satyagraha campaign came in 1907, protesting a South African law requiring the registration and fingerprinting of all Indians, further allowing the police to enter any Indian home without a warrant to oversee compliance.

Gandhi’s volunteers – mainly teenage boys – peacefully picketed the government’s registration centers, under strict orders not to bother or hinder any Indians who wished to comply with the new law. Only about five percent of South Africa’s Indian population did. In 1908, Gandhi was sentenced to two months in prison, but was out of jail in a matter of days for talks with the government of General Jan Smuts.

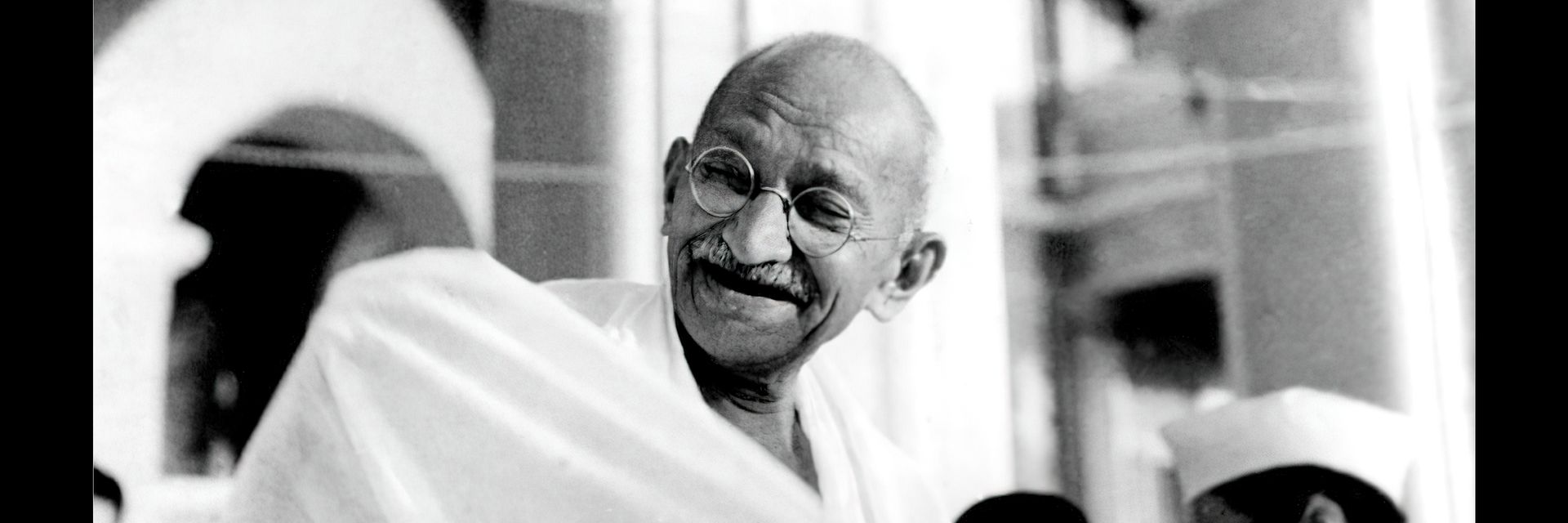

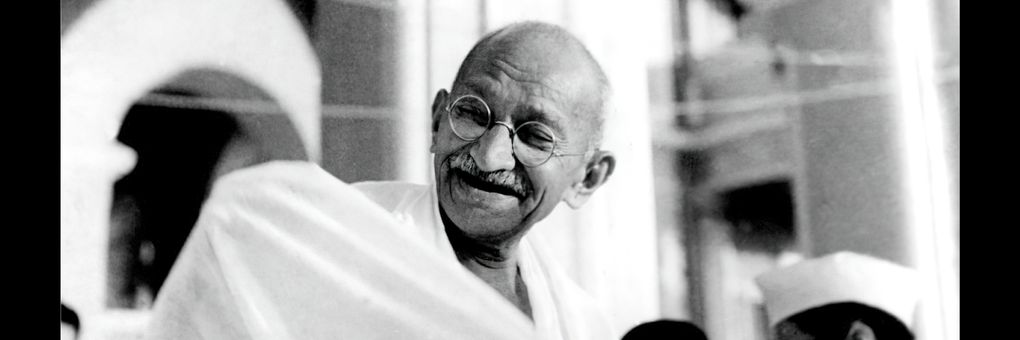

Gandhi in 1931. (Source: Wikipedia)

An agreement was reached, then broken by the Smuts government. Civil disobedience by Gandhi’s followers filled the jails while Gandhi was jailed twice in six months. In 1912, the Smuts government broke a promise to repeal a poll tax on indentured workers, while the nation’s Supreme Court ruled that all Muslim, Hindu, and Parsi marriages lacked legal standing.

Gandhi’s next move was to organize a mine workers strike, while mobilizing Indian women to march on the coalfields. Thousands were arrested, prompting a general miners strike. The South African government now added beatings and shootings to mass arrests. Public opinion across the British Empire swung firmly in favor of the strikers, support reaching the highest levels of government. At a mass meeting to mourn dead miners, Gandhi appeared for the first time in the traditional Indian robes and leggings that characterized his personal attire for the rest of his life.

Satyagraha, a brilliant contemporary opera by the American composer Philip Glass, tells the story of Gandhi’s first civil disobedience campaign using lyrics drawn exclusively from the Mahabharata, his favorite sacred Hindu text.

When white miners went on strike, Gandhi announced the suspension of all further political action. With a full labor stoppage, the Satyagraha movement ended all active demonstrations against the South African government. General Smuts, in the words of historian George Woodcock, “was now cornered by public opinion.” In 1914, the Indian Relief Act passed. It restored Indian marriages, halted the poll tax, eased immigration laws, and phased out the indentured servant system.

Though these measures did not stop the increasingly racist laws of 20th century South Africa, Gandhi had notched an outstanding victory at the time, and in July 1914 he returned to India to focus his Satyagraha movement on a new cause – the granting of India’s independence from the British Empire.

Gandhi’s Vision for India and the Limits of Satyagraha

In the following years, Gandhi employed Satyagraha in a series of strikes, fasts, acts of civil disobedience, and stints in jail, usually with thousands of his followers. He recognized that his success in India was less by way of the movement’s pure expression than the need for British authorities to protect his personal safety. In the wake of World War II, granting independence to British colonies worldwide was inevitable.

Satyagraha’s success also depended on a civil authority that, however restrictive, recognized basic human rights. Summary executions, torture, and imprisonment without trial – common features, for example, of Czarist and Communist Russia, and Nazi Germany, rendered any Satyagraha movement in vicious totalitarian states deeply moot.

By 1945, Gandhi’s vision of a better India – homespun, and given to universal acceptance of cultural differences – had been overtaken by one emphasizing urbanization and economic development. Furthermore, the partition of the former Raj into two separate states, one Hindu and the other Muslim, was the final blow to Gandhi’s ideal India. Now politically irrelevant, Gandhi was shot in January 1948 by a Hindu extremist objecting to his vision of a tolerant, pan-religious nation.

Satyagraha’s Lasting Influence

As a template for just social action, in rules for engaging issues of fairness and tolerance in otherwise hostile and flawed democratic systems, Satyagraha has proved enormously effective in various social campaigns. This influence was felt most significantly in the work of Dr. Martin Luther King in the 1960s civil rights movement, as well as in death penalty reform, international ecological protests, and broad demonstrations against deadly police violence in the United States.

Satyagraha has become less a series of hard-and-fast strictures than a means of engaging social change in a deeply moral way. If its victories have been small and hard won, they have also been lasting.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.

Title Image: A portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, ca. 1940. (Source: Wikimedia)