Forensic genetic genealogy led to the identification of the Golden State Killer, with a great many other cases following suit. But how does it work? And is it ethical?

◊

Decades ago, it might have seemed like a sci-fi fantasy. A small box arrives in the mail containing deceptively simple instructions and a plastic collection tube. Collect your sample (i.e., spit into the tube), empty a small vial of stabilization buffer to the sample, and send it to a laboratory for testing. And wait. The results can be a veritable window into one’s identity, potentially revealing not only distant ancestral origins but, once shared via online platforms tied to the tests, leading to the discovery of living family members. Some tests can also reveal genetic predispositions to diseases and other conditions, allowing individuals to take preventative measures.

While DNA tests can be eye-opening to people in search of knowledge about their genetic makeup, the results of such tests have come to serve another surprising, yet equally important, purpose. Forensic genealogists, in hand with law enforcement, have used these platforms to find familial matches to DNA left behind at crime scenes, thus enabling them to solve cold cases and missing persons cases that have long baffled detectives. While CODIS (the Combined DNA Index System) contains DNA samples from known offenders, public DNA databases open up the pool considerably.

For more on the fascinating science of crime investigation, check out the Forensics series on MagellanTV.

How it Works

While obtaining a sample and submitting to a direct-to-consumer DNA testing company is relatively effortless, the process of creating a DNA profile, or genetic sequencing, is a complex one. As 23andMe reports, once a sample arrives at a third-party laboratory, geneticists isolate DNA from the sample, amplify the sample (or duplicate the amount first extracted from the saliva), then “cut” the amplified DNA into smaller fragments. These are then applied to a DNA microarray or chip, a slide featuring microscopic beads that attach to probes. The DNA pieces stick to the DNA probes, enabling scientists to determine genetic variants.

Because all humans are roughly 99.6 percent identical in their genetic makeup, genetic sequencing relies on detecting variants within the remaining 0.4 percent. The more markers that are identified, the more complete a genetic profile will be.

While a genetic test can tell an individual a lot about their heritage, there are no guarantees for law enforcement when attempting to track down familial DNA matches. In order to make a match, family members of individuals who left their DNA behind at a crime scene will have had to voluntarily upload their own DNA results. These family members need not be close relatives to provide valuable clues, however.

As more and more individuals purchase kits and set out to learn about their genetic makeup, the likelihood of tracing familial DNA to crime suspects increases. And no matter how long ago a crime was committed, if a biological sample (such as blood, skin, hair, or semen) taken from a scene contains DNA (and the sample hasn't been compromised), it remains viable.

But when a partial genetic match is found, a puzzle is still left to unravel—a family tree to be reconstructed root-to-root, leaf-to-leaf. If, after piecing together a family tree, a suspect is identified, investigators are tasked with collecting a fresh DNA sample and verifying it’s a match to the original DNA.

Familial DNA Cracks a Notorious Cold Case

In her posthumously published book, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, author and online sleuth Michelle McNamara documents her years-long obsession with identifying the Golden State Killer, who was responsible for a series of burglaries, rapes, and murders in California from 1973 to 1986. She includes the following ‘letter’ to the serial murderer, still a phantom at the time she wrote it:

One day soon, you’ll hear a car pull up to your curb, an engine cut out. You’ll hear footsteps coming up your front walk. Like they did for Edward Wayne Edwards, twenty-nine years after he killed Timothy Hack and Kelly Drew, in Sullivan, Wisconsin. Like they did for Kenneth Lee Hicks, thirty years after he killed Lori Billingsley, in Aloha, Oregon.

The doorbell rings.

No side gates are left open. You’re long past leaping over a fence. Take one of your hyper, gulping breaths. Clench your teeth. Inch timidly toward the insistent bell.

This is how it ends for you.

‘You’ll be silent forever, and I’ll be gone in the dark,’ you threatened a victim once.

Open the door. Show us your face.

Walk into the light.

McNamara tragically passed away before the identity of the Golden State Killer was revealed. The case took a turn in 2018, when a team led by cold case investigator Paul Holes, who had been searching for the Golden State Killer for 24 years, uploaded a DNA profile obtained from a semen sample from a rape kit to GEDmatch. This unveiled third cousins of the culprit.

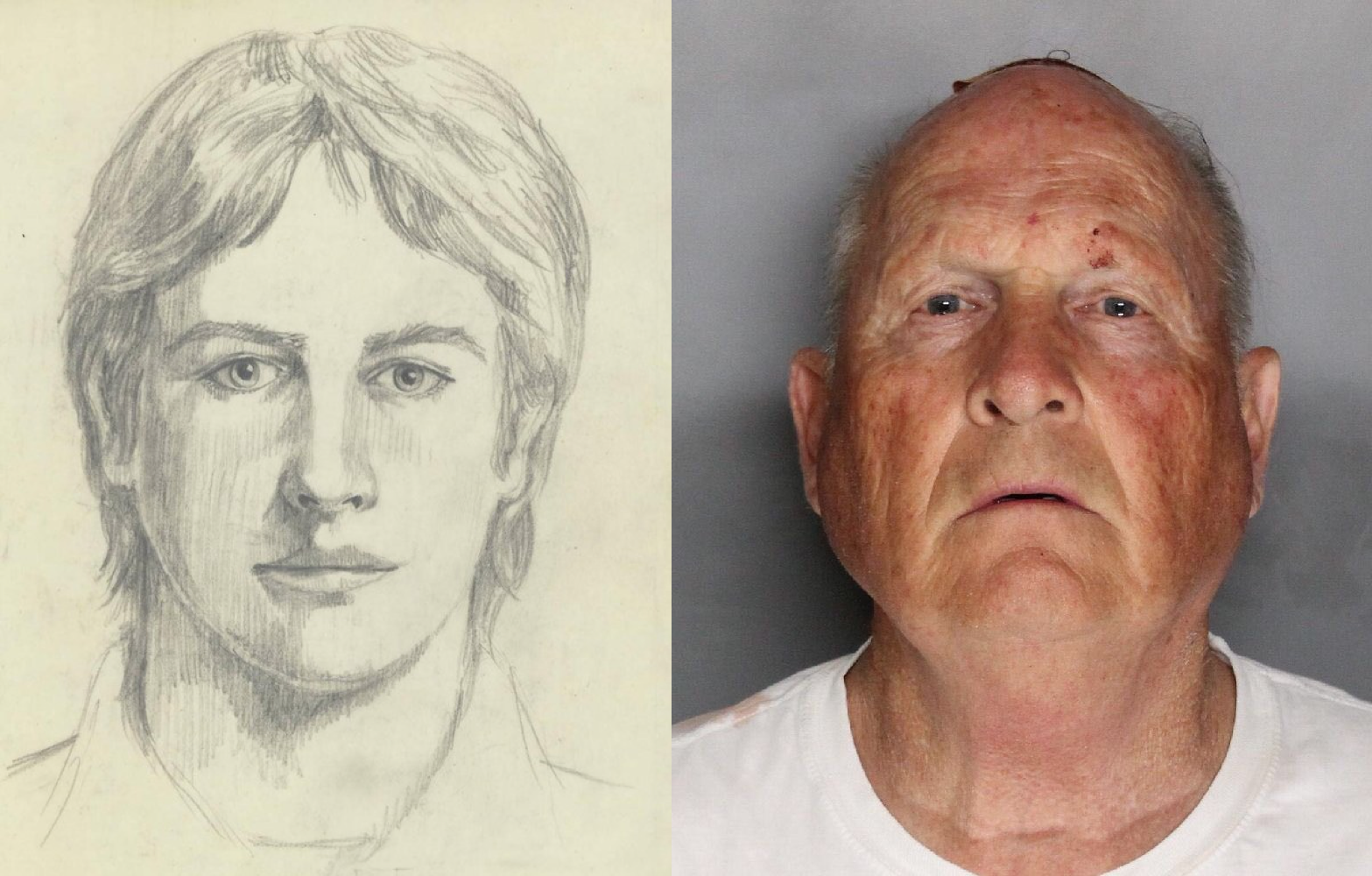

The FBI visited one of the cousins, a woman living in Orange County, and requested her DNA. This sample, in turn, revealed that the Golden State Killer was a relative on the woman’s side of her family. Eventually, the family trees narrowed the suspect list to six male cousins. Physical characteristics previously established in the suspect’s profile — notably, his blue eyes — squarely pointed to Joseph James DeAngelo, a former police officer, as the Golden State Killer.

Golden State Killer police sketch vs. DeAngelo’s mugshot. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The FBI surveilled DeAngelo and retrieved objects from his trash, which were compared to the original sample. It was a match, and DeAngelo was arrested in 2018. He was convicted in 2020 of 13 counts of first degree murder and 50 rapes; he was sentenced to life in prison.

Since DeAngelo’s conviction, hundreds of other cases have been solved using forensic genealogy. In addition to finding those responsible for crimes, these tactics have also been used to identify previously identified victims of crimes.

In a unique case, familial DNA revealed both the victim’s identity and the culprit’s. In March 2022, investigators announced that they had identified a body first discovered on a Georgia highway in 1988 by using familial genealogy DNA. The victim was Stacey Lyn Chahorski, a woman who had been missing from Michigan for more than 30 years. Via forensic genealogy, they also identified the man who had killed her: a trucker named Henry Fredrick Wise.

In November 2022, Joseph George Sutherland, a 61-year-old Toronto man, was arrested and charged with the sexual assaults and murders of Susan Tice and Erin Gilmour in 1983. In 2000, detectives linked the trace DNA found at both scenes. Genealogy allowed investigators to locate the suspect’s relatives and subsequently arrest Sutherland.

Even more recently, in 2022, Bryan Kohberger, a doctoral student studying criminology in Washington State, was arrested on suspicion of brutally murdering four Idaho college students living in off-campus housing. Investigators found the suspect’s DNA on a knife sheath left behind at the scene. While law enforcement has remained somewhat tight-lipped about the methods used to catch Kohberger, it’s been widely reported that genetic genealogy played a role. Undoubtedly, more details will be unveiled during Kohberger’s upcoming trial.

Civil Rights Concerns Arise

While familial DNA was instrumental in identifying, arresting, and prosecuting Joseph James DeAngelo Jr., the case raised concerns about the public’s privacy and law enforcement access to genetic information. Since DNA analysis has become a trusted tool within forensics, it has often been regarded as infallible. But can DNA evidence always be trusted?

(Credit: CardioElena, via Wikimedia Commons)

When studying DNA left behind at a crime scene, investigators must take into account the near ubiquitous nature of trace DNA and its tendency to linger. Criminal defense attorneys have raised questions about when a particular DNA sample was left behind at a scene (a defendant might have entered a room and sat on a couch hours before a crime took place) or whether an object found at a crime scene was touched by the suspect in a circumstance unrelated to the crime itself. It becomes critical to rule out extraneous genetic profiles, a practice that is baked into crime scene investigation. However, concerns about false allegations based on DNA evidence persist.

In May 2022, a New York court suspended familial DNA searching after a group of Black men expressed fears that they would be targeted by law enforcement because their brother’s DNA had been found at a crime scene (siblings share approximately 50 percent of their DNA.) However, the ruling only pertained to the state’s DNA databank, and not to public genealogy sites. The Legal Aid Society made a statement following the ruling, saying, “We laud this decision which affirms our serious constitutional, privacy and civil rights concerns around familial searching, a technique that disproportionately impacts Black and Latinx New Yorkers.”

While human error remains a potentiality in all investigational processes, when the science is used correctly alongside other techniques, it’s an indispensable tool for solving violent crimes.

And, if an individual’s DNA can lead to the arrest and imprisonment of a killer as reprehensible as DeAngelo, do such privacy concerns — and fears of false accusations — pale in comparison to the achievement of a higher good?

Beyond restrictions on state databases, many direct-to-consumer companies have regulated law enforcement access. In fact, currently only two databases, GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA, do not require a warrant for investigators to obtain information. At the same time, however, alternative resources are becoming available.

A Forensic DNA Project Makes Strides

In 2022, forensic genealogists CeCe Moore, Chief Genetic Genealogist at Parabon NanoLabs, and Margaret Press, who co-founded the DNA Doe Project, launched a nonprofit DNA database called DNA Justice. It’s the first and only not-for-profit database used exclusively for forensic genetic genealogy and depends upon citizens voluntarily submitting their DNA profiles.

Moore, who has helped identify some 250 violent criminals and human remains, is passionate about the benefits of forensic familial DNA. “It’s the biggest breakthrough in crime fighting and locating missing persons since DNA was first used in law enforcement in the ’90s,” Moore told MagellanTV. She launched the foundation over concerns that GEDMatch and FamilyTreeDNA may eventually restrict law enforcement access. It was critical to have a backup resource.

CeCe Moore (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

But the DNA Justice project is still in its infancy and faces real challenges, including financial barriers. “We have to start from scratch. It will take a long time to grow our database to the point we will be able to solve crimes,” Moore says. She remains hopeful that the current number of profiles will increase exponentially. This would be game changing. “If there were 20 million we could help law enforcement solve 98 percent of violent crimes. But we would be thrilled to get one million people.”

The fact is that millions of people already have the information they need to assist in building the foundation’s database — to be specific, anyone who has utilized a genealogy test kit and received their profile. Moore urges anyone who feels they want to assist in solving potential crimes or missing person cases to submit their DNA profiles. She adds that she encourages individuals to make an informed choice; the purposes behind the project are made entirely transparent. The DNA profiles utilized by the DNA Justice project are also never shared publicly.

The power of genetic genealogy as a forensic tool is undeniable, and the benefits to living victims and families can be immeasurable. “When genetic genealogy is able to help law enforcement, it does change families’ lives,” Moore says. “I don’t think that families of victims ever have true closure, but some answers and some resolution.”

Certainly not everyone will choose to submit their genetic profiles, and it’s entirely their choice. But, despite continuing controversy over forensic genetic genealogy, to use a proverbial expression, the genie is out of the bottle. Only, DNA is surely not myth or magic: it’s science.

As DNA Justice attracts more participants, cases both recent and long-cold, will undoubtedly be solved. Those responsible for the most unconscionable of acts will “walk into the light.”

Ω

Matia Query is a freelance writer and the editor of BookLife, the indie author wing of Publishers Weekly. She lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Title Image credit: Kadumago, via Wikimedia Commons)