Coming soon after the winter solstice – and the longest night of the year – the new year and its attendant celebrations mark a season of fresh hope and expectations for the next trip of the Earth ’round the Sun. But how, and why, was this particular moment in the annual calendar chosen to start things off? Why January? The answer is stranger – and more complicated – than you may think.

◊

As the old year draws to its end and the new one appears, ready to assume the mantle, let’s pause and reflect on how this all started. Now, I don’t mean how “all this” started: That is a topic for another time. I simply mean to refer to the passage of the months, and how each year begins with January and unravels till the endpoint of each year in December.

The new year seems naturally to bring along with it a sense of hope, fresh beginnings, and a mixture of plans and resolutions for how things will unfold as the months and seasons pass. But why does this all start in the virtual dead of winter? Why not start along with the new blooms and sprouting good times of early spring? Why January and not, say, March?

Well, it turns out that’s not such an outlandish idea. Others have had and implemented such ideas in ancient times. In fact, in the evolution of the Western calendar there was a time when the winter months weren’t included at all in the passage of the months: They just weren’t counted.

Later, during the height of the Roman Empire, the honor of being the first day of the year was formally bestowed on the mid-month date of March 15 – the ides of March! – before being moved provisionally, almost by accident, to a date that stuck, January 1. More on that follows.

Click to stream "Rome: Empire Without Limit with Mary Beard"

Early Calendars Relied on the Sun and Moon

The earliest attempts at calendar-building date from prehistory, and are termed lunisolar to refer to their practice of following the phases of the Moon and the seeming “movement” of the Sun and its cycles, or seasons, of influence on the Earth.

In the early days of ancient Rome, as the city-state was first being established, there are signs that a rudimentary calendar was constructed whose main purpose seemed to be to help farmers with planting and harvesting cycles. The oldest written Roman calendars are composed of just ten months, with the first month corresponding to the beginning of spring – and the start of the season of planting and growth – and ending ten months later when the fields lay fallow in anticipation of the next cycle.

Naming the Months from a Preliminary Base of 10

Early moves to give a title to these colder months brought forth a combination of nomenclatures that honored gods of the Roman pantheon (including the appropriated Greek goddess Aphrodite), names that celebrated Roman rulers, and those that simply called attention to where the months lay in sequence.

March (Martius, in Latin) and April (Aprilis or Aphrilis), the early months, took for their namesakes Mars and Aphrodite, the Roman god of war and the culturally adapted Greek goddess of love, thus expressing two of the strongest and most significant elements of the Roman character. In Roman mythology, Mars was romantically entwined with Venus, the goddess who assumed Aphrodite’s place in the Roman pantheon. The result of their union was Cupid.

Botticelli's The Birth of Venus (based on the Greek myth of Aphrodite)

May (Maius) and June (Iunius), months of activity and commerce, were represented by the gods Maia and Juno. Maia is a goddess who personifies fertility, a key to growth and prosperity of both farmer’s crops and the community’s expansion. Juno is the goddess of marriage, and June has historically been the most popular month for weddings in Western culture (until recently).

July (Iulius) and August (Augustus) are honorifics that represent two key leaders of the early Roman Empire: July is named for Julius Caesar, who led the expansion of Rome as a conquering power throughout the Hellenistic world during his lifetime (100 to 44 BCE), and was born in this month. And August honors Caesar Augustus (63 BCE to 14 CE), who greatly expanded his predecessor’s empire and named this month himself to honor the military successes he achieved during this time of the year.

Long before the Roman Senate stepped in and bestowed naming rights for two months to honor two significant public figures, these months existed, with their names following the conventions of the later, “numbered” months. July, originally the fifth month, was named Quintilis, after the Latin name for five; August was called Sextilis, for its former sixth place in the procession of the annual calendar.

The rest of the months, the “ember” months from September through December, simply represent their order in the original 10-month Roman calendar. September derives from septem, meaning seven; October from octo, meaning eight; November from novem, or nine; and finally December, from decem, meaning ten. And so, our beloved end-of-cycle twelfth month was actually the original final player in a 10-month sequence!

January and February are Born for the Dark Days of Winter

Keep in mind that during Roman times no name was assigned to the span of 60 or so days between the end of December and beginning of March. These were days “out of time,” so to speak, uncounted days when not much happened, other than storehouses of grain being slowly depleted, until the next planting season would begin in the wet and muddy days of early spring.

This system was maintained for hundreds of years after the first rudimentary calendars were devised. Then, in 713 BCE, the Romans, under King Numa Pompilius, decided to “annex” the remaining days of the lunar cycle and separate them into two roughly equivalent periods, becoming two new months at the end of the calendar sequence.

Moon phases (Source: Sergio-sq via Pixabay)

I imagine persons born in the formerly unnamed period were grateful finally to be able to say with certainty when their birthdays were! Though I have been unable to find reference to this in my research, it must have been a relief to be able to say something other than, “I was born in the “uncounted times.”

For more fascinating discussion of the Roman Republic and its empire, view the series Rome: Empire Without Limit, available on MagellanTV.

Inspired by the Roman god Janus, January became the eleventh month in the Roman calendar. Even though the month was toward the end in the sequence, it was seen as a “gateway” to the next cycle. Linking its name to Janus was an apt choice, as he oversaw many facets related to change, including beginnings, transitions, and endings. (He was also the god of doorways, portals, passages, and gates.)

Finally, February was created as the final month of the year for the Roman calendar. It was a month of preparation for spring and all the promise it held. The word February derives from the Latin februum, meaning purification. This part of the year was already the time of the official Roman feast of purification, Februa, celebrated during the full moon, just before the beginning of the new year in March.

How Did January Become the First Month?

During this era of the Roman Republic (509 to 27 BCE), years were not numbered but were named for the consuls appointed by the Roman hierarchy to govern over the Republic for set periods of time. Consuls served the Republic with terms that began (for the most part) on March 15, as that was considered not only to be the beginning of their terms but also the start of the yearly cycle marked by the calendar.

Rome’s territory expanded, making inroads into regions where other calendars were used – so as the Roman Empire grew, so did the (enforced) use of the Roman calendar system. But not everyone accepted Roman rules and culture peacefully. Some territories either resisted the advance of the Empire, or rebelled against it. For example, there is the history of Taras.

It was during a period of colonial upheaval that a small but extraordinarily significant change was made in consular appointments – and in the Roman calendar system. Around 154 BCE, a rebellion broke out in the colony called Hispania, present-day Spain. There was a need for decisive action to quell the uprising, and new consuls were selected early.

Since consuls were not only governmental leaders but also military commanders, and since the Roman year was set to coincide with the consular year, the date of new consular terms had to be moved up to allow for new military leadership. So, as an element of practical military strategy, this change was instituted on January 1 in the year 154 BCE. And it stuck.

The Roman Forum in Rome at sunset (Source: Stockbym via Adobe Stock)

In succeeding years, the consular year and calendar year coincided. January wasn’t ever meant to be the first month of the year. Happenstance and military strategy just made it turn out that way. Eventually, in 46-45 BCE, when Julius Caesar instituted a series of reforms in the dating system that became known as the Julian calendar, January 1 officially remained the first day of the year, and so it has continued to today.

The Western Calendar: One Among Many

Of course, I’ve been discussing only the Western calendar, the one that evolved from pre-Roman Etruscan times to the one we in the West use today. There are numerous other calendars currently in use, such as the Islamic calendar, the Jewish calendar, the Chinese calendar, and more, as well as other calendaring systems that no longer hold sway, such as the one devised by the Mayans. Each of them has a story at least as interesting as this, and could be the subject of its own article.

But let’s pause here and consider how far we’ve come, and what lies ahead. After all, it’s the New Year’s season, a time when, like the god Janus, we typically take a moment or two to take stock of our lives, assess possibilities and probabilities, and set out our plans for the coming 12 months.

In this, perhaps, we are not too different from our Roman forebears, who also used this “month of Janus” to ponder the quiet period between the end of autumn and the beginning of spring. And, for us in the Northern Hemisphere, we can look forward to the first green shoots of springtime, so promising, and just a few more months away.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

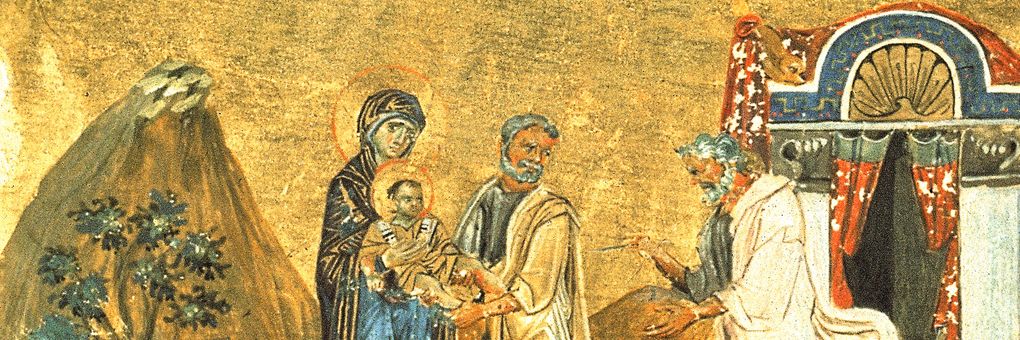

Title Image: For Christians, January 1 traditionally marks the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ. (Source: Wikimedia)