Expanding from its origins as enforcers working for feudal landowners in Sicily (as explored in Part I of this article), the Mafia eventually drew the attention of law enforcement across the Atlantic Ocean in New York City. Infamously, a dedicated Italo-American detective investigating Cosa Nostra was assassinated in Palermo.

That a hero New York City cop was murdered with impunity while on an undercover assignment underscored how the Mafia was evolving into an international criminal enterprise. Once established in the United States, Sicilian mobsters muscled their way into the business of older established gangs outside the Italian community. But the money and power that flowed through the 20th century Mafia led to deadly rivalries between warring “families” in both Italy and the U.S. The violence unleashed in Sicily in the 1990s appalled the nation and led to prosecutions that hobbled the Mafia, hopefully forever.

◊

The brazen 1909 Palermo killing of New York City Police Detective Joseph Petrosino announced a new phase in the Mafia’s development. In the previous century, this deeply clannish, violent cadre of rural Sicilian bandits and bosses went from gangs of enforcers hired to protect the vast feudal estates of Sicily’s rulers, to political power brokers in the newly unified Italy.

Now, following the high tide of emigration of southern Italians to the United States, these obscure criminal bands established themselves in the new country. At first, they preyed exclusively on the Italo-American community, with theft, threats of violence, kidnapping, and extortion, before inevitably branching out into the illegal businesses of long-established American gangs: gambling, loansharking, counterfeiting, hijacking, and prostitution.

The late Det. Petrosino’s NYPD squad mainly held the Sicilian mob in check over the decade after his killing, with convictions and deportations of the first generation of Mafia members. But once the 1919 Volstead Act made the production and consumption of alcoholic beverages illegal, bootlegging and speakeasies brought a fresh river of money – and opportunities to bribe police and politicians. The Mafia, alongside Irish, German, and Jewish criminal gangs, became as American as hotdogs and pinball machines, which were soon joined by jukeboxes as another cash-intensive source of mob income.

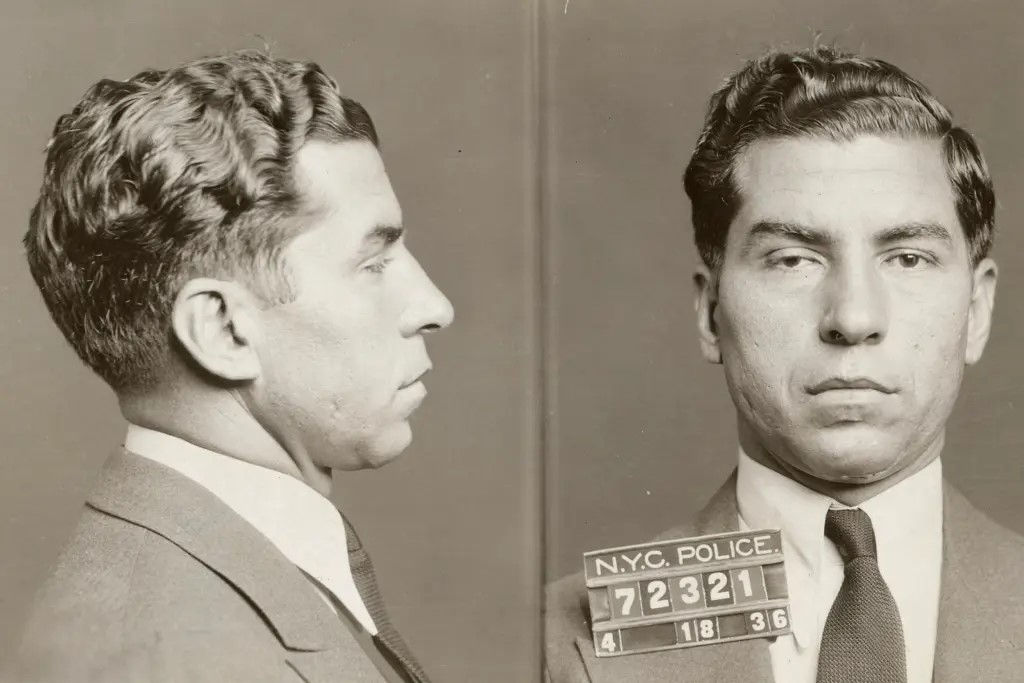

Charles "Lucky" Luciano, 1936 (Source: New York Police Department, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Seeking to exploit the new opportunities offered by Prohibition, the Sicilian boss, Vito Cascioferro – the man who privately confessed to Petrosino’s murder after being found not guilty of the crime – sought to exercise control of the American mob from his Palermo base. A bloody turf war between gang factions ended with the defeat of Cascioferro’s Sicilian network by a thoroughly Americanized mob crew headed by one Salvatore Luciana, aka Lucky Luciano.

In Italy, the arrival of Mussolini’s fascist government in 1922 offered the first existential threat to the Mafia in its history. On his first trip to Sicily, Il Duce was astonished to be offered personal protection by a smug local mayor. Enraged that anyone might assume more power than himself, Mussolini initiated a brutal crackdown on Mafia gangs that employed methods of interrogation and imprisonment last used during the Inquisition.

The vicious anti-Mafia campaign proved highly effective and the organization was driven deep underground. For that, the Sicilian author Leonardo Sciascia, who wrote knowingly of the Mafia’s government connections, observed that Sicily was the only Italian region to experience greater freedom under fascist rule.

Watch Mafia And Italy: A Bloody Pact now on MagellanTV.

A Place for the Mafia in Post-War Europe

The negative consequences of Mussolini’s crackdown became apparent during World War II once Allied forces drove the fascists from the island in 1943. The American command needed reliably anti-fascist administrators for Sicily’s local governments. Mafiosi fit the bill, but the consequences of this arrangement apparently did not bother the Americans until it was too late.

The supposed influence of Lucky Luciano, then jailed in the United States, in preventing any Sicilian resistance to the Allied invasion is an urban legend. But the fact remains that the landing itself went nearly without incident, and Luciano was released from prison and deported to Italy in 1946.

Now add wartime black market profiteering to the Mafia’s income flow. The island became a source for goods stolen from Army supply lines, such as food, clothing, and, especially, cigarettes. This revived black market network was readymade to carry increasing shipments of narcotics – one more Mafia money-spinner – in the ensuing postwar years.

The American Mafia thrived during the American Century. It extended its businesses into the drug trade (by the 1980s, the Sicilian branch supplied an estimated three-quarters of the U.S. heroin traffic), and it was the driving force behind the creation of Las Vegas as a gambling Mecca. Investigations and Senate hearings did little to reign in a highly organized criminal enterprise that more than a few sympathizers in the U.S. and Italy insisted did not really exist.

Italy’s central location gave it far-reaching importance in Western Europe’s Cold War order. Home to the largest Communist Party outside the Iron Curtain, control of national elections there became a matter of real concern in Washington. Consequently, tremendous U.S. aid, overt and covert, was instrumental in supporting the center-right Christian Democratic Party that ruled the country for half a century.

Crucial to this realpolitik arrangement was Mafia control of Sicily’s votes in parliamentary elections. Here was the apotheosis of Cosa Nostra power. It now ran a network of politicians and administrators who protected a full spectrum of criminal activity, including illegal waste disposal and corrupt construction companies, along with the murder of political rivals, in exchange for electoral victory.

Thanks to popular movies like The Godfather and Goodfellas, “Mafia” has evolved from an Arabic-Sicilian word for a localized criminal group to a term used now for any nationally defined crime organization, such as the British, and Russian mafias.

Such corruption may have been long-standing, but it was ultimately unstable. By the mid-1960s, the Mafia’s overwhelming success, and the mountain of money it generated, began to fray traditional loyalties. Greed and lust for control set competing Mafia chieftains against each other in bloody vendettas in both Sicily and the United States. These internecine wars lasted years, as rival factions reached a new level of violence in disposing of their enemies.

Palermo Becomes a War Zone

The bloodshed was especially appalling in Palermo, which by the early ’80s resembled a war zone, with daily body counts that included police, judges, legislators, and journalists. But the unprecedented violence changed everything. Sicilians had had enough of the killing and corruption. The Mafia could no longer be tolerated as a traditional, albeit grim, social feature.

Brave journalists began documenting gangland crimes, while newspaper photographers, especially the renowned Letzia Battaglia, provided graphic and abject depictions of the aftermath of the killings. Some mafiosi even began talking to law enforcement after feeling betrayed by their business associates. For the first time since Mussolini’s anti-Mafia campaign, Sicilian prosecutors and judges, who knew full well the danger they were in, began a series of investigations that resulted in trials and convictions.

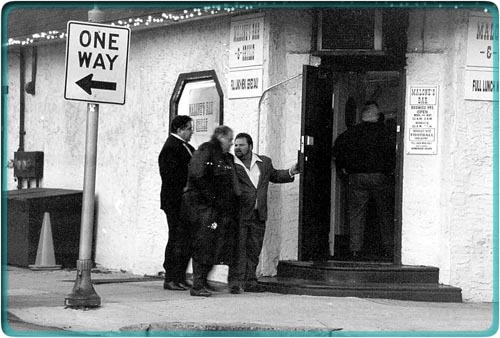

Mafia informant and former Philadelphia police officer-turned-mobster Ron Previte (center), 2001 (Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

The most famous of these crusaders was the Palermo-born magistrate Giovanni Falcone, who guided a series of investigations that led to the so-called Maxi Trial, in which nearly 500 mafiosi faced a multitude of charges. Housed in a specially constructed, bunker-like courtroom attached to Palermo’s main prison, the trial lasted, from opening arguments to final appeals, from 1986 to 1992. Convictions were obtained against 338 of the accused, who were sentenced to a combined 2,665 years in prison – not counting 19 life sentences for the worst offenders.

Transferred to Rome in the wake of the trial, Falcone was reorganizing the state’s anti-Mafia legal apparatus when, on a return to Palermo five months after the Maxi Trial ended, he, his wife, and bodyguards were killed by an enormous highway bomb. Four months after that, Falcone’s Palermo successor, Paolo Borsellino, was murdered in another huge explosion outside an apartment building in that city.

Over 80 years after the brazen murder of Det. Petrosino, the tragic assassinations of the two magistrates in the same city induced revulsion across Italy, leading to the Mafia’s loss of its unquestioned grip on Sicilian life.

The Mafia, Down Now But Not Out in the 21st Century?

By the end of the 20th century, prosecutions, arrests, and imprisonments in Sicily and the U.S. had dramatically reduced the Mafia’s reach and power. Associations of businesses, hundreds of shops, hotels, and restaurants, refusing to pay for mob “protection,” appeared. Of course, the Sicilian mob is not the world’s only criminal network, or even the only one in Italy. And its illegal trade was quickly taken by others.

In June 2021, Giovanni Falcone's killer was released after 25 years behind bars. The parole of the hitman, who confessed to some 150 murders, enraged Italians and underlined the Mafia's continued presence in the country, albeit diminished from its powerful peak.

In 2019, 126 members of the Neapolitan Camorra were arrested in a broad sweep, while January 2021 saw another maxi trial, this one against 320 members of the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta. The jury, you could say, is still out regarding whether these and further measures will be enough to smash the gangs. History has shown that there is never a shortage of people ready to do the wrong thing, to value money and power over decency and law.

And the Sicilian Mafia has certainly demonstrated an ability to evolve as the society around it changed. Still, it is hard to see it surviving without the traditional loyalty, secrecy, and fear it once commanded. Openness and transparency are online conditions of 21st-century social life worldwide. A remnant of the Dark Ages, the Sicilian Mafia thrived in the shadows of 20th-century life; shadows that, with effort, may be banished for good.

Ω

Title Image: Shots fired through glass (Source: Oleg Malchakov, via Adobe Stock)