The history of fine art on TV reached an early apex with Kenneth Clark’s Civilization series of the 1970s. Now, following in those esteemed footsteps comes a different kind of TV art host, more contemporary and certainly more willing to challenge (rather than lionize) cultural assumptions about art and art history. This man is Waldemar Januszczak. Just how does he “get behind the canvas” to illuminate the world surrounding the art?

◊

On an otherwise unremarkable day several years back, I was wandering through the Impressionist galleries in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The rooms were crowded, it being a nice Sunday afternoon, and for a while I was stuck behind a couple having an extremely animated conversation on the gifts Impressionism brought to the world of art.

Waldemar Janusczcak (Source: Wikimedia)

“It was form that made the Impressionists great,” one of them said, ensuring that those encircling her were aware of the words she spoke.

“No, it was light that was the Impressionists’ greatest gift,” her companion distinctly challenged her.

“I’m sure it’s form,” she self-assuredly – and somewhat reductively – added to the conversation, and the two continued talking as they toured the 19th century’s European avant-garde cultural expression.

Paul Cezanne – Mont Sainte Victoire

I wanted to interrupt them and ask, Can’t it be both? But what I really wanted was for an art-history expert to step up and educate us all on light, form, color, movement, composition, and technique – not to mention luxe, calme et volupté – as they relate to the Impressionists’ remarkable body of work.

Seeking an Authority on Art for the Masses

I imagine I’m not the only person in the world who’s wanted to appeal to an art authority when confronted by an aesthetic squabble in a museum or gallery. Despite didactic panels mounted next to the works on display, and even prerecorded self-guided tours, a live (not to mention lively and well-informed) host/interpreter is an ideal companion when you want to move past simply observing into a rich appreciation of works of art.

“Art history didn't write itself. Somebody came up with its storylines. And those somebodys had reasons for doing it that cannot always be trusted.” – Waldemar Januszczak

Of course, most of us won’t have the opportunity to visit all the most impressive museums in the world, so it’s up to mass media to amplify the voice of the art “interpreter.” To that end, for the past 50 or so years of televised media, we’ve had a stream of TV personalities introduce us to art in all its full-color glory.

A (Very Brief) History of Art History on TV

Kenneth Clark is perhaps the best known of all TV art presenters; his series Civilization began its broadcast life in the U.K. in 1969 and became a staple of U.S. public television broadcasts in the 1970s. He was followed by such savvy, charismatic fine-arts hosts as John Berger and Robert Hughes, whose brash Shock of the New series burned up the artsy airwaves in the 1980s.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, we had the late Sister Wendy Beckett, who communed with art on the TV screen throughout the English-speaking world. Her inimitable, idiosyncratic personality, and her obvious love of art and artists, made her kind of a cult personality during those years, and her renown persists through today.

Byzantine icon: Virgin Mary and Christ Child

Recently, the BBC and PBS teamed up to produce a new version of Clark’s landmark series, calling it Civilizations. Not only did the show expand the rather narrow Western focus of its predecessor to embrace the substantial contributions of societies around the world, but it also featured a diverse trio of excellent presenters – Simon Schama, Michael Olusoga, and Mary Beard. Whether these three intrepid guides will be knighted or made life peers by their monarch, as was Clark, remains to be seen.

Waldemar Januszczak and the Democratization of Art

The 21st century has also seen the welcome rise of another broadcast art historian, U.K.-based Waldemar Januszczak. A unique and sometimes divisive figure, Januszczak has been called everything from an “iconoclast” and “cool guy” to a “gnome” with an “intellectually inebriated” attitude. His enthusiasm, however, is hard to miss. He’s used his academic background in art history, along with his experience as an art critic for British publications, to present such entertaining, informative TV art-historical excursions as The Impressionists and The Renaissance Unchained, brisk yet deep examinations of the art and artists of each era surveyed.

Januszczak was born in England to Polish immigrants. His father was killed in a traffic accident before Januszczak was a year old. He was raised by his mother, who worked as a dairy maid (it was the 1950s, before factory farms automated that process) to help make ends meet. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there were few jobs available at that time in Britain for a Polish woman who spoke little to no English.

“People would rather see frogs shagging in the Amazon than a great Raphael. Why is that?” – Waldemar Januszak

Januszczak claims not to have felt strongly the absence of a father in his upbringing. But he did have one thing that he formed a strong attachment to: art. Rather than surrendering to the limitations encountered by most working-class immigrants, Januszczak was drawn to his studies in art history, and graduated from the University of Manchester with a degree in the subject. He then parlayed his academic background into a career as a journalist and art critic.

Raphael – Self-portrait

Januszczak does not lack gratitude. “Art saved my life,” he explains. “Art history lifted me out of a dark immigrant’s experience.” He continued, “I couldn’t speak English till I was six. But I could look at paintings . . . at all the glorious art-historical evidence that survives from the history of humanity, and I could enjoy it and learn from it.”

Januszczak’s Life Work: Celebrating and Communicating the Power of Art

Januszczak’s life experience has made him into a surprisingly direct, even charismatic TV performer, presenter, and interpreter of visual art. His upbringing gave him an outsider’s perspective on the upper classes, elites, and connoisseurs who traditionally owned the keys to the art-world kingdom.

This outsider’s perspective, combined with the joy of someone who profoundly believes in the life-saving potential of the arts, makes him a delightful presenter. His approach, which we see in subjects ranging from Hans Holbein to Frederic Remington, is enthusiasm for the artwork, discernment for the artist’s technique and skill, and a seemingly endless interest in the life represented in and by the art.

Hans Holbein – Portrait of Sir Thomas More

Here, I think, is Januszczak’s special genius as a guide to his viewers: He is a master not only of, for example, technique, but also the artist’s approach to his surroundings, the artist’s and her model’s social standing, how the work was received by audiences of the time, and how we see the work today.

Experiencing Life Through Art

As much as possible, Januszczak actually seems to see “through” the paintings he discusses to the reality of the life behind and beyond the canvas. In this he is more than an art connoisseur, more than an art historian – he is actually a social historian, reconstructing historical narratives from the strands of documents, artifacts and works of art that, as he says, survive “from the history of humanity.”

“From the heroic cowboy art of Frederic Remington to the pictorial gunslinging of Jackson Pollock, who turned up in New York in a Stetson and cowboy boots, the Wild West has always been make-believe.” – Waldemar Januszczak

One of the most appealing qualities of Januszczak’s personality and unique onscreen presence is the absence of elitism. He appears to be devoted to sharing with his viewers the common humanity of the artists, subjects, and themes he addresses. He also takes great pleasure in “upsetting received opinions about art and art history.”

This iconoclasm is on full display in Januszczak’s 2014 miniseries Rococo Before Bedtime and again in his 2016 documentary series The Renaissance Unchained. In these engaging films, he picks apart the many standard points of view we’ve picked up in school and elsewhere. In the first, he explores the widely held belief that the Rococo Age was a period of frivolous, overwrought experimentation in design, and deploys a wealth of surprising examples drawn from literature and music, as well as visual art, that show the serious contemplation of form and meaning hidden beneath the common misconceptions.

Fragonard – The Swing

In The Renaissance Unchained, Januszczak discovers centers of artistic production and innovation in many areas of Europe outside Italy. But, even so, he doesn’t deny us the glories of Italian Renaissance art. He states that Renaissance art is not simply – or even mainly – an “awakening” from a “dark” age, but an explosion and rapid influx of new ideas, materials, and techniques that liberated artists to a point “bordering on madness.”

“Seeing the World Afresh”

Januszczak can be forgiven his occasional paroxysms of delight (and perhaps exaggeration) when revealing uncovered facts and connections through the artists and works he discusses. In fact, this unpredictable flowering of unexpected points of view have allowed him to stand out and be recognized as a premiere presenter. Audiences seem to feel they have a personal, intimate relationship with this relatable guide. It’s as if they’re receiving insights from a friend rather than a stern, remote intellectual.

Arts and media critic John Preston responded to Januszczak’s approach to art by remarking, “the effect of being led round by the hand here was akin to seeing the world afresh after a cataract operation.”

And this is what matters, after all. Januszczak represents a new type of art lover, one who cracks jokes in the museum, shocking the bourgeoisie as he strips generations of received thinking from the canvases we observe. Instead, he offers us the delight of seeing historic objects with clarified vision. He encourages us to slow down a bit, take a break from 21st century media oversaturation, and rest our eyes and mind on one object, or a group of related objects, that open up the world – and our place in it – in unforeseen ways. By inviting us to share the delight he so obviously feels, he makes us his partners in discovery.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

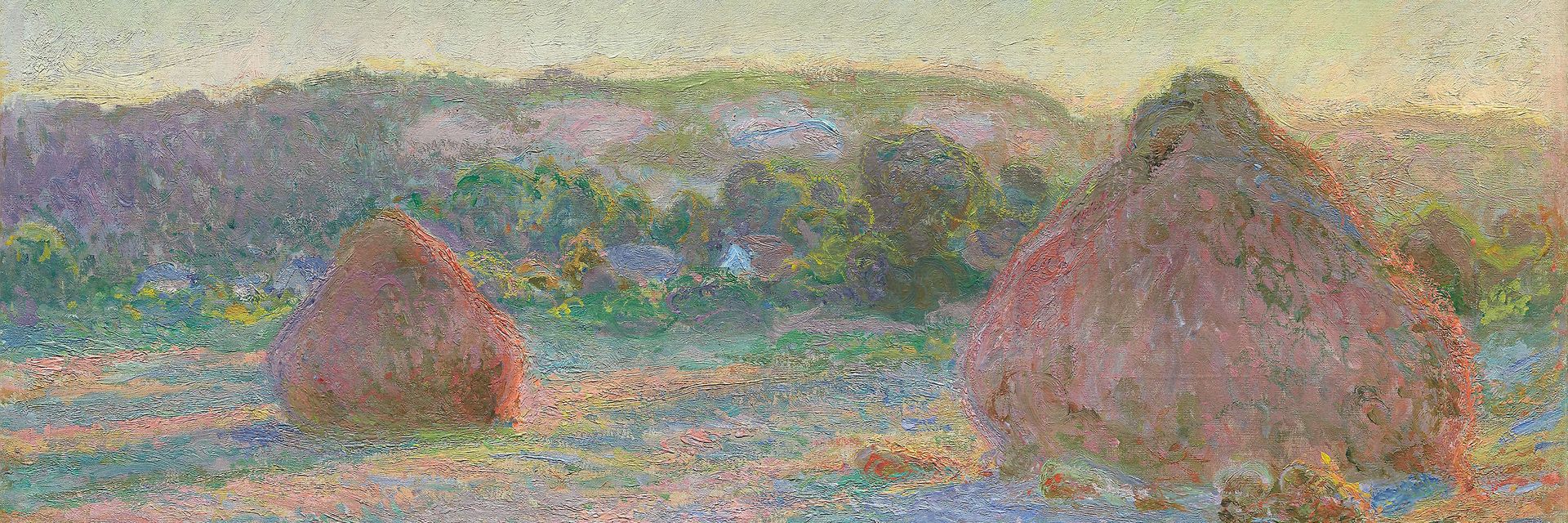

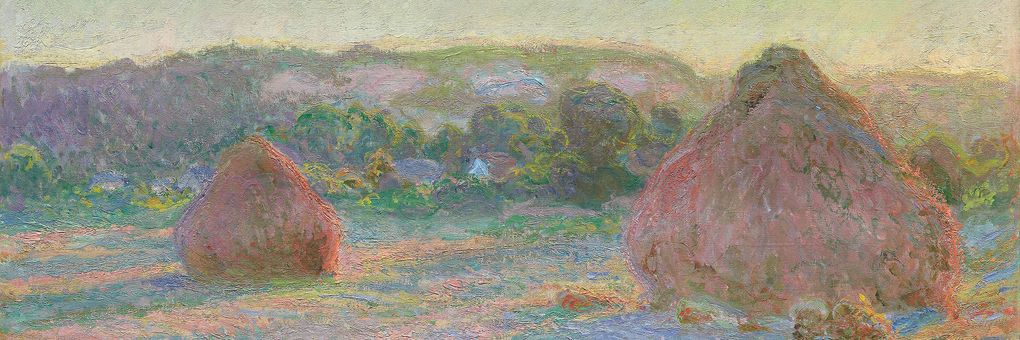

Title image: Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) by Claude Monet (Public Domain) via Wikimedia Commons.