The 1947 independence of India and Pakistan was a triumph of anti-colonial struggle overshadowed by partition’s deadly cost and Mahatma Gandhi’s unfulfilled dream of a united, peaceful subcontinent.

◊

After decades of political struggle, negotiation, and social upheaval, Pakistan and India gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1947 on August 14 and 15, respectively. This historic moment put an end to British colonial domination, but the transition to self-rule for the two nations was far from smooth, leading to one of the world's most tragic human calamities.

Journalists visit both sides of the India/Pakistan border more than 70 years after partition in this probing three-episode MagellanTV documentary.

Early Nationalism and the Rise of Gandhi

The Indian National Congress (INC), founded in 1885, became the primary vehicle for Indian nationalism. Initially seeking more inclusion within the British government, its goals shifted toward full independence. In contrast, the All-India Muslim League, established in 1906, emerged to protect the political rights of Muslims in a Hindu-majority India. Tensions between the two organizations intensified as independence became a more likely prospect.

In the 1920s, Mahatma Gandhi became a central figure in the Indian independence movement. He promoted nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience, mobilizing millions through campaigns like the Salt March in 1930 and the Quit India Movement in 1942. Gandhi’s philosophy emphasized Hindu-Muslim unity, self-reliance, and peaceful protest. However, despite his efforts, communal divisions deepened.

During World War II, the British relied on Indian support but failed to grant promised autonomy, which led to widespread dissatisfaction. After the war, Britain, weakened economically and politically, recognized it could no longer maintain control. The Labour government in Britain began moving toward decolonization.

Gandhi’s decision-making during this period was marked by his insistence on nonviolence and unity. He strongly opposed the idea of partition, believing it would lead to bloodshed and long-term conflict. However, the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, feared that Muslims would not be safe in a Hindu-dominated India. Their solution was a separate nation, Pakistan.

Leaders of the All-India Muslim League in 1940 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Partition and Tragedy

The British proposed several plans to maintain a united India with power-sharing between Hindus and Muslims, but none succeeded. The increasing violence between Hindu and Muslim communities in the mid-1940s convinced many leaders, including Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel of the Indian National Congress, that partition might be the only practical solution, even though Gandhi continued to oppose it.

Eventually, faced with growing communal violence and political deadlock, the British government announced in June 1947 that it would grant independence to India and allow for partition. In August, Pakistan and India achieved full -- and separate -- independence.

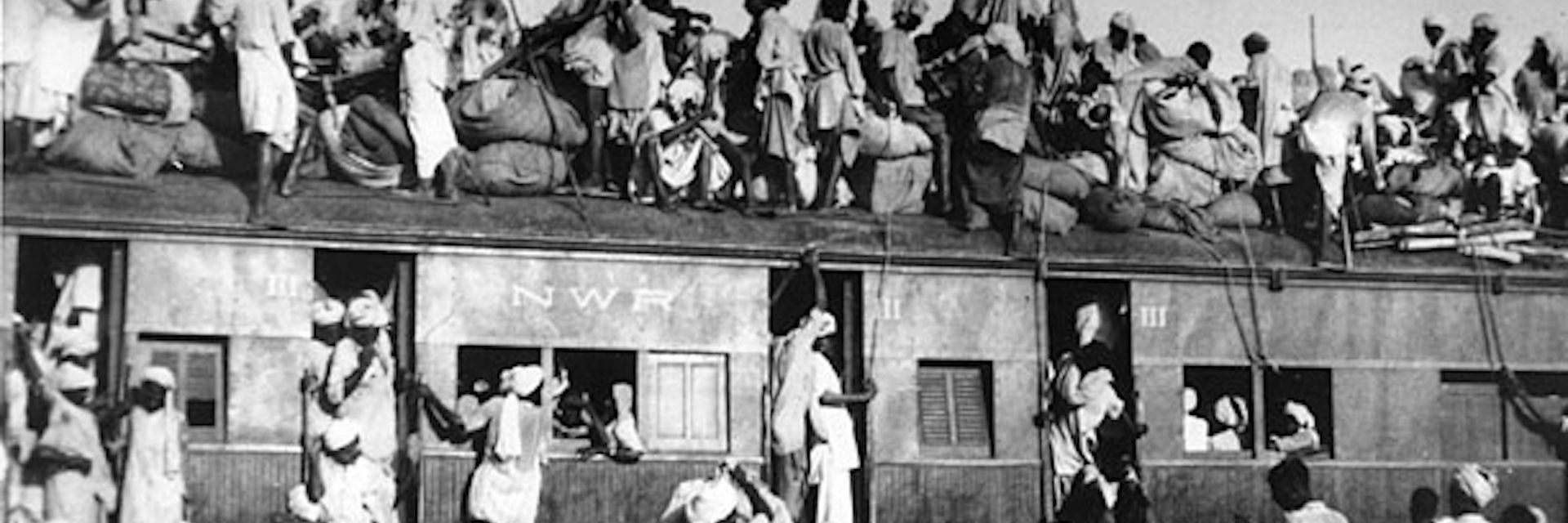

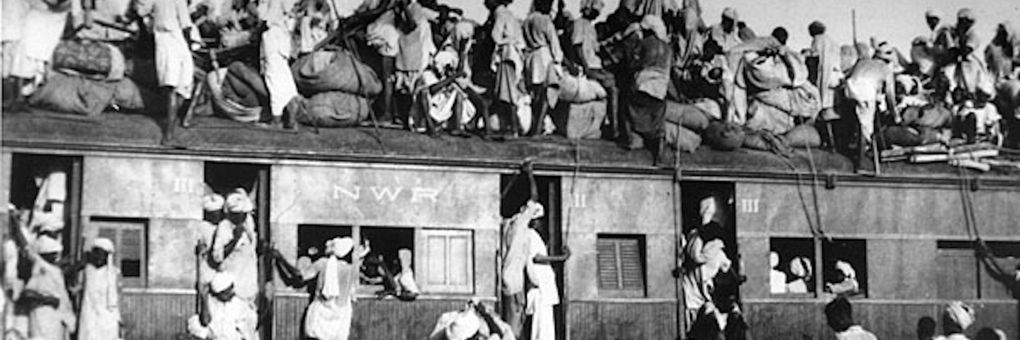

The partition led to one of the largest mass migrations in history, as around 10-15 million people crossed borders to join their religious majorities. The process triggered widespread violence, with estimates of up to one million people killed in communal riots.

Gandhi was deeply disheartened by the violence. He spent his final months fasting and advocating for peace between Hindus and Muslims. He was assassinated on January 30, 1948, by a Hindu nationalist who believed Gandhi was too sympathetic to Muslims. His vision of a united India in which Hindus and Muslims would coexist amicably was in tatters. Several decades later, a lasting peace between Pakistan and India remains elusive.

Ω

Title Image: Overcrowded train transporting refugees during partition of India, 1947 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)