It took remarkable scientists and safe vaccines to defeat the scourge of polio.

◊

From the early to mid-20th century, few diseases provoked more dread than poliomyelitis, generally known simply as polio. Although most infected people never developed symptoms, a relatively small percentage were struck by severe symptoms. Worse, the large majority of victims were children under the age of five, leaving families gripped by fear during the summers, when infections tended to spike.

By the 1940s and early 1950s, polio had become a terrifying seasonal visitor in the United States and much of the world, causing tens of thousands of cases annually. The public pools and playgrounds that symbolized carefree childhood were suddenly suspect. Parents, desperate to shield their children, turned to quarantines and makeshift preventions. Yet until science intervened, the disease spread relentlessly, indifferent to class or geography.

Follow dedicated scientists on the hunt for infectious diseases in this three-part MagellanTV series.

Declaring War on Polio

In severe cases of polio, the virus invaded the central nervous system, leading to muscle weakness, paralysis, or even death. Hospitals and clinics struggled to care for those afflicted, pioneering mechanical ventilators like the “iron lung” to help patients whose respiratory muscles failed. Photographs of rows of children encased in these giant metal cylinders became a haunting emblem of the era.

By the late 1940s, after World War II ended, resources became available for an intensified war against polio. Researchers understood that the key lay in harnessing the body’s immune response through vaccination. The battle involved contributions by many scientists, but two brilliant doctors led the charge.

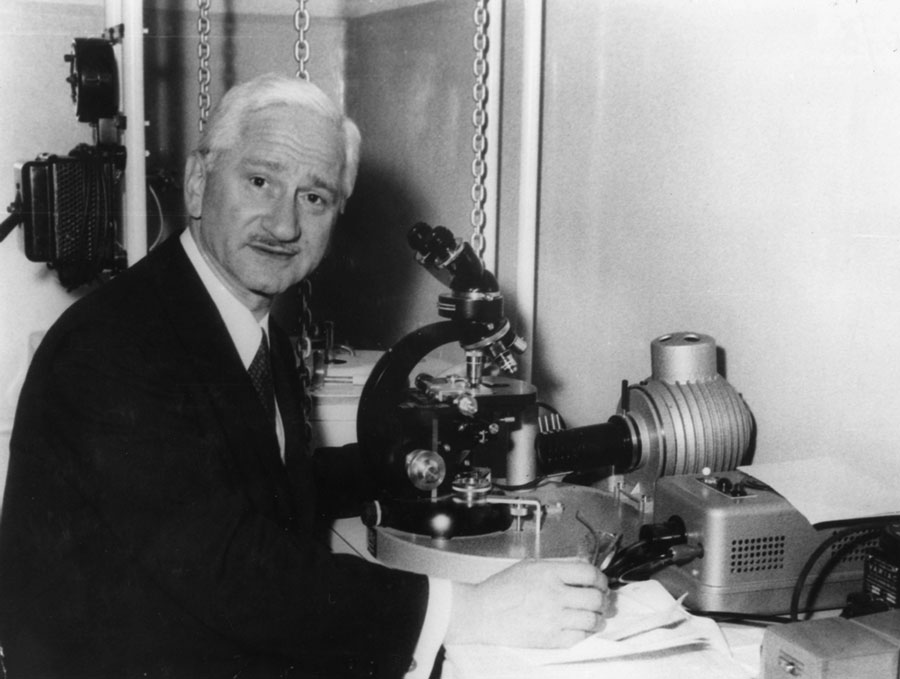

At the forefront was Jonas Salk, a young virologist at the University of Pittsburgh, who embarked on developing a vaccine using inactive versions of the virus – a strategy that would allow the immune system to build defenses without risking active infection. Meanwhile, some 470 miles down the Ohio River at the University of Cincinnati, Albert Sabin, pursued a different solution: an oral vaccine based on a weakened, live virus, which he believed would mimic natural infection and provide longer-lasting immunity.

Dr. Jonas Salk at the Copenhagen Airport (Source: SAS Scandinavian Airlines, via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Jonas Salk at the Copenhagen Airport (Source: SAS Scandinavian Airlines, via Wikimedia Commons)

Vaccines Lead to Victory Over Polio

Salk achieved the initial breakthrough. After painstaking laboratory work and cautious testing, a large-scale clinical trial began in 1954 – one of the largest public health experiments ever conducted. In April 1955, over 1.8 million American children, dubbed “Polio Pioneers,” received injections of either the vaccine or a placebo. The results dramatically demonstrated that the Salk vaccine was safe, effective, and ready for mass production.

That success, however, was dependent on strict adherence to guidelines in preparation of the vaccine. A tragic error known as the Cutter Incident unfolded when a batch of improperly inactivated vaccine led to 40,000 children contracting polio from the very shots meant to protect them. This setback spurred tighter government oversight of vaccine production and highlighted the delicate tension between scientific innovation and public trust.

Despite early missteps, immunization efforts accelerated, with the mass immunization of millions of children. In the 1960s, Albert Sabin’s oral vaccine was licensed, offering a cheaper, easier-to-administer alternative. Delivered on sugar cubes or in drops, the Sabin vaccine rapidly gained favor worldwide, particularly in regions where injection campaigns faced logistical barriers. Together, the Salk and Sabin vaccines transformed polio from a feared household word into a preventable disease.

Dr. Albert Sabin (Credit: D. Orsini and M. Martini, via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Albert Sabin (Credit: D. Orsini and M. Martini, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sustaining a Successful Vaccine Strategy

The broader impact of these vaccines transcended polio itself. Their development galvanized modern vaccine science and cemented the idea that public health triumphs could spring from robust collaboration among researchers, governments, and ordinary citizens. Fundraising campaigns, such as the March of Dimes – initially supported by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, himself paralyzed by polio – rallied millions of Americans to support research and patient care, forging a model of civic engagement in medicine.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Basil O’Connor (Source: March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, via Wikimedia Commons)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Basil O’Connor (Source: March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, via Wikimedia Commons)

Today, polio has been driven to the brink of extinction. Thanks to global vaccination campaigns spearheaded both by major institutions like the World Health Organization and by community groups such as Rotary International, wild poliovirus remains endemic in only a few regions of the world. Yet the story of polio’s conquest serves as a cautionary tale as well. Resurgent cases due to armed conflict, deplorable misinformation campaigns, or lapses in vaccination remind us that diseases can claw their way back if vigilance wanes.

More than half a century after the first shots went into young arms, the legacy of the polio vaccines endures as one of the 20th century’s greatest scientific triumphs. They stand as a testament to human ingenuity, the power of collective action, and the promise that even the most daunting medical threats can be overcome when society unites behind science.

Ω

Title Image: Polio victim standing with the help of braces and canes (Source: Agency for International Development/National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons)