American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was first known for building extraordinary houses for wealthy patrons. But when the Great Depression hit, he responded with new ideas for the new face of America.

◊

In a career that began before the dawn of the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright was America’s first starchitect. That term – a portmanteau of star and architect – was originally applied to celebrity architects almost a century later, people like Philip Johnson and I.M. Pei, who were as personally famous as the works that brought them fame. Wright fits this definition to a T. Like many geniuses, he lived an outsized life. He could be a difficult and demanding, even authoritarian, taskmaster to his students and junior colleagues. And, with his multiple marriages, interspersed with scandalous affairs, he seemed to relish flying in the face of convention. Nonetheless, his daring, visionary designs for homes for wealthy clients gained him international renown.

Wright abhorred the Victorian style of architecture in vogue across the U.S. in fin-de-siècle America. Its stuffy rooms and fussy design were anathema to him. After breaking with his mentor, Louis Sullivan, in 1893, he began his quest to make a uniquely American architecture. This revolutionary approach featured open spaces, long, horizontal lines, and harmony with nature – just like the Midwestern prairie where he’d been raised. In fact, he termed it his “Prairie Style.”

But this was only his first foray into distinctive, eye-catching styles of architecture. From his first design to his last, he saw architecture as the “mother art,” an instrument that he wielded to, in his view, make the world more beautiful and ascribe meaning to the very act of living. He wanted to create “total environments” where every element contributed to the overall aesthetic. But how would he react when the whole world changed before his eyes?

To learn more about America's greatest architect, watch Frank Lloyd Wright: The Man Who Built America.

Wright Makes His Name Building Houses for the Rich

In the first two decades of the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright became very wealthy through the many commissions he received to build luxurious homes, replete with servants’ quarters, for clients in the Upper Midwest. Many of the homes were sited in his home state of Wisconsin and in Chicago, where he set up his first independent office. Wright was determined to craft a new style for America, one free of foreign influences and steeped in a culture of optimism and possibility – a truly American style. He called it “organic architecture.”

Hollyhock House terrace (detail), Los Angeles. (Credit: Library of Congress)

One splendid example of organic architecture is his residence for the heiress Aline Barnsdall in Los Angeles, completed in 1922. Called the Hollyhock House, Wright sought to ground his design in the natural landscape of the American Southwest, with which he’d recently become acquainted. The architect chose a native plant, the wild hollyhock, as the guide for his design innovations, imprinting a stylized form of the hollyhock stalk on scores of concrete blocks that he used for both structural support and decoration; he called these textile blocks.

The dramatic look of the interiors of the Hollyhock House was very influential in the scenic design for Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi film Blade Runner, a dystopian view of an alternate future.

Then, catastrophically, the “Roaring Twenties” came to a crashing halt in October 1929. The bottom of the U.S. stock market fell out, triggering a worldwide depression that extended through the 1930s. Wright called it a “national breakdown,” and for good reason. His client base of privileged landowners vanished, leaving him with hardly any work. What was a visionary domestic architect to do?

The Great Depression Leads Wright to Conceive a New ‘Usonian’ Style

The ’30s were a turbulent time for the world, and Wright, despite his wealth, was not unaffected.

He had a new wife, his third, and decamped with her from the Midwest to the Southwest, purchasing land in Arizona to establish a new studio, living space, and workshop that he called Taliesin, also the name of his previous atelier and estate in the Wisconsin countryside.

Life at the original Taliesin had ended horrifically for Wright’s staff and loved ones in 1914, when a crazed employee set fire to the complex and murdered seven people with an ax. The attacker killed Wright’s mistress and her children; Wright was away at the time.

The new Taliesin proved to be a boon to Wright. He attracted students to the sprawling property and involved them in his new plans, which would broaden his vision to incorporate the rapid changes in the way people were living. Wealthy families were dismissing their servants, and people were of necessity seeking smaller, more affordable living spaces.

Wright refined his vision for an “organic” architecture for the American people. He sought to extend his vision to the “common man,” and developed plans to house masses of citizens in exurban developments. He sought to avoid metropolitan areas, which Wright disdained along with their skyscrapers – he viewed them as “monstrous.” He sought a new model for living, one that incorporated people at all levels of society, and with his students and colleagues at Taliesin West, devised plans to create a utopian community based on his new philosophy, which he termed “Usonian.” It was, one might say, a genial approach to American nationalism.

Usonian Ideals: A New Vision for Community Housing

This was a new day. And it required a new approach. Wright was a man whose vision encompassed both the beautification of the world and the improvement of American society through architecture. He proposed a style that celebrated the American way and heritage, utilizing nationalism to instill pride and a sense of common purpose in its citizens. He promoted these ideas under a rubric created from loosely initializing the phrase United States of North America – hence, Usonia.

In this, he was influenced by the 19th-century Progressive thinker Henry George, who advocated that America’s land and resources should belong to all equally. Wright ran with this idea and conceived of an America where all were able to own a plot of land, separate from the “disappearing city” (which Wright wrote about in his book of that title in 1932), and to live in a diverse community of fellow citizens. And automobiles, introduced just as Wright started designing homes, would be essential for a more mobile America.

Wright sought a place for the American ideals of freedom and ingenuity while retaining privacy within a tightly knit community. To that end, and in keeping with George’s principle, he envisioned communities of citizens living in fully functional but stripped-down homes of his design. He even added in a few multi-family structures, with room for those who chose to live an apartment lifestyle.

What Were the Characteristics of a Usonian Home?

Wright’s homes for his Usonian community would be models of efficiency. He considered six characteristics to be foundational:

- Simply designed, L-shaped small houses

- Single-story, with no basement or attic

- Native, locally sourced materials

- Cantilevered overhangs, including space to park an automobile that he termed a “carport”

- High, clerestory windows to add natural light

- Public/private division, opening in the back to natural surroundings

An example of Wright’s Usonian architecture, the Gordon House. (Credit: Andrew Parodi, via Wikimedia Commons)

To make the project work, construction needed to be simplified as much as possible. The basics of designing a residence, including heating, lighting, and sanitation, required novel solutions to keep costs low. Wright employed a new style, but maintained his vision, by radically paring down extra or unused space. He designed built-in features for seating and storage to keep the homes’ footprint down to a minimum.

To make the construction of Usonian homes available to the broadest swath of the citizenry, Wright designed what he called Usonian Automatics, prefab versions of these homes meant to be assembled by amateurs. While in production, 11 kits were sold.

Broadacre City: Wright’s Vision for an American Community

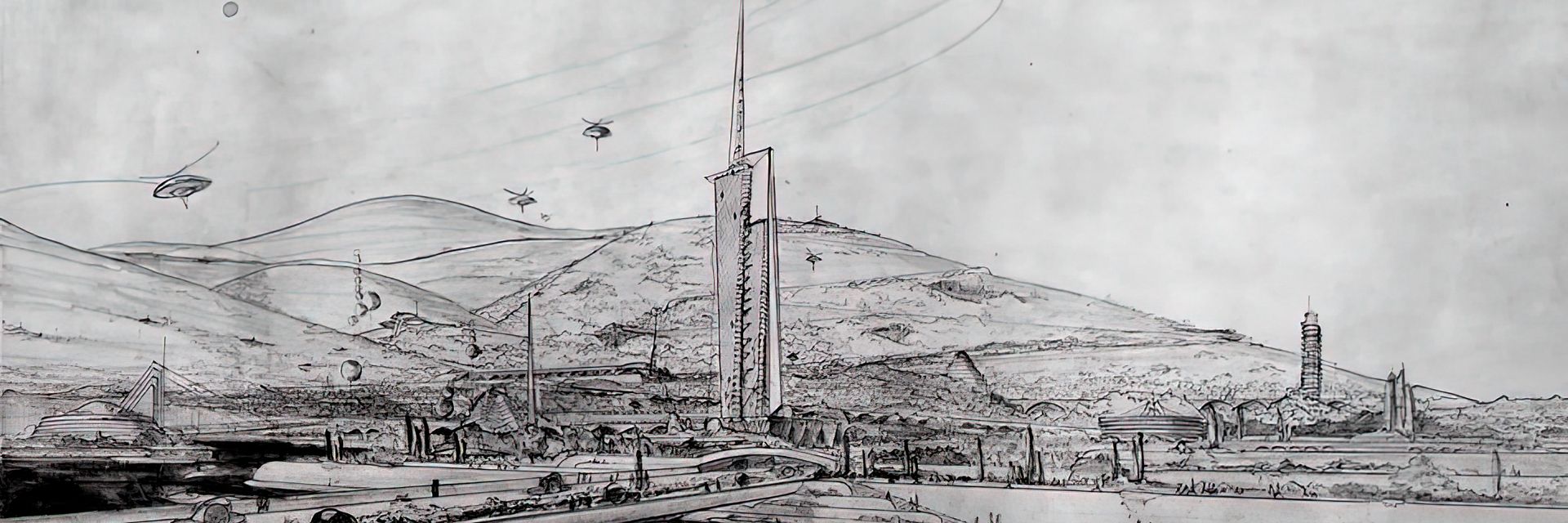

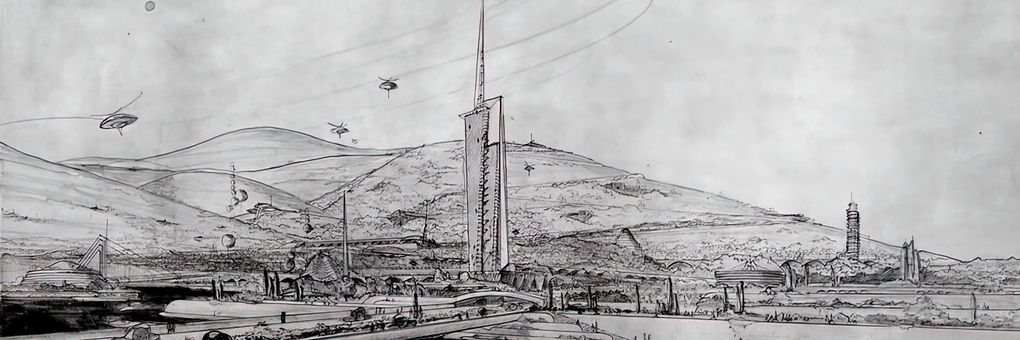

To demonstrate these concepts for a “Usonian” development, Wright had his students build a 12-foot-square model of a sample community he titled “Broadacre City.” The model was displayed in various places around the U.S. in the mid-’30s. It was never built, and it’s not clear quite how serious Wright was about turning the Broadacre City concept, in particular, into reality.

However, Wright was successful in working with clients of modest means, eventually getting 60 examples of this style of private home built in various places in the U.S. There was even an attempt by Wright acolytes to construct a Usonian development near Pleasantville, New York. On 100 acres of land, 47 Wright-approved designs were built, four of them designed by the master himself. While his vision for an interconnected, self-sufficient community was never realized, the ideas he presented, particularly his ideas for simplified home construction, have been influential to this day.

Beyond Usonia: Wright’s Later Work

As the 1930s progressed, Wright continued pitching his Usonian ideas, but, along with improvements in the economy, larger commissions started coming his way. Whether domestic or public, Wright followed his vision for an organic architecture. It was at this time that he undertook what many consider to be his singular achievement in an organic “design for living,” the home called Fallingwater, completed in 1939.

Fallingwater (Credit: Photo by Kirk Thornton on Unsplash)

Located in a sylvan landscape south of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the home – a weekend residence for a wealthy businessman’s family – was envisioned to be grounded in the topography of the site. Positioned over a small waterfall in a meandering creek, the house almost magically seems to rise above the landscape, fully a part of its surroundings. Consistent with his near-dictatorial ideas about organic design, Wright also created a full set of accessories for the home in keeping with the natural elements: tables and chairs, furnishings and light fixtures.

Perhaps, of all his works, Wright’s most significant contribution to American culture was his design for the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, a project he worked on for more than 14 years beginning in 1943. He created a novel space, in the form of a conch shell, where visitors walked in gently sloping concentric circles to observe modern art, within the context of a structure that was a contribution to art – of its time and today’s – as well.

The Guggenheim Museum, New York. (Credit: Joe Dudeck on Unsplash)

Wright was a true American visionary. His designs connected Americans to the natural landscape, a constant source of inspiration to him. He also worked at a human scale, fixing the proportions of homes and buildings to give comfort to their inhabitants and visitors, while inspiring awe not by overwhelming scale but by the intimacy of the experience. Over the course of his long career, he completed 532 projects, mostly houses. It is fitting, considering his influence and reach, that he was named in 1991 the greatest American architect of all time by the American Institute of Architects.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Frank Lloyd Wright sketch for Broadacre City. (Credit: Wikimedia, Kjell Olsen, originally posted to Flickr)