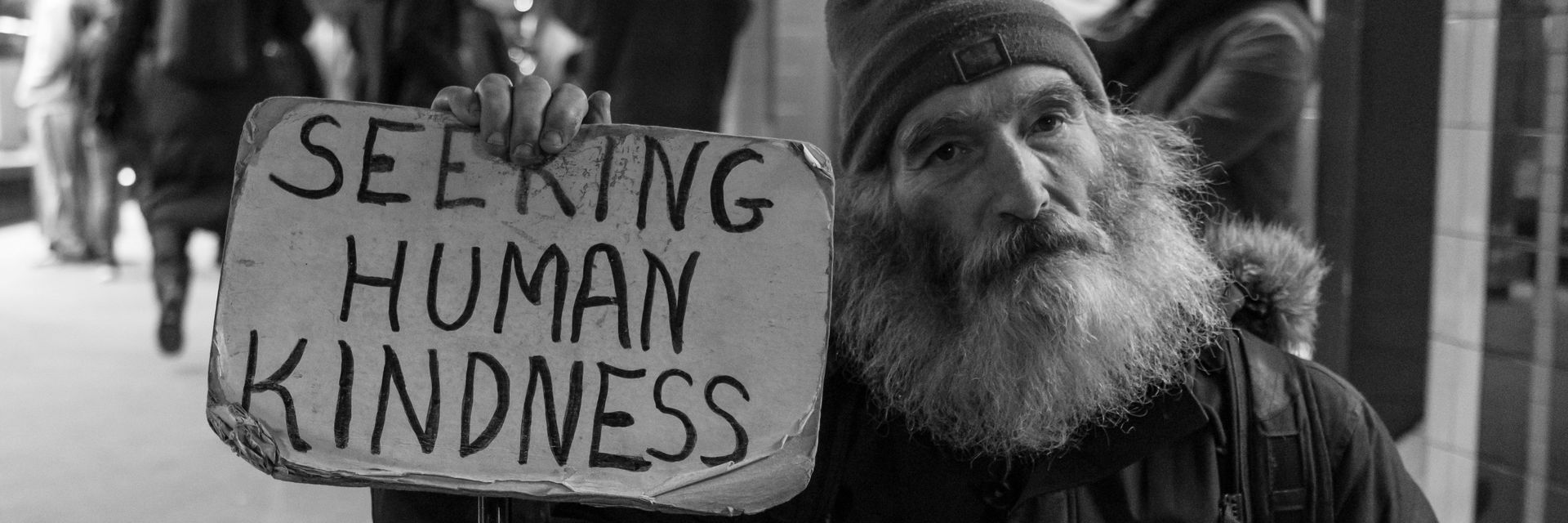

What are sympathy and empathy, where did they originate, and how are they different?

◊

Imagine a world without laws, without societies. How would life be? According to 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, human life outside a social contract – that is, in a state of nature – is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Ouch. Without a social structure, people do what it takes to survive. If you’re clever, you could outwit a muscle-bound dolt, but if said dolt happens upon you while you sleep, it’s game over.

If observations about the natural world are any indication, Hobbes’s account is plausible. The world is a dangerous place. There are predators and prey, on land and in the sea, and survival is not only the relentless objective of life, but it’s an objective relentlessly fraught with danger.

It’s no wonder that Hobbes thinks humans are motivated by self-interest in ways that would seem to obviate feelings like compassion, sympathy, and empathy. After all, if my overriding motivation for everything I do is what I believe is in my best interest, I don’t have room for other motivations.

Hobbes does acknowledge “fellow feeling,” which arises when one sees suffering and (shudderingly) imagines the same happening to oneself. Still, this version of pity or compassion is felt through the lens of self-interest – it’s less about someone else’s suffering than it is about my concern for my own potential misfortune. Yet genuine concern with and for others – concern not tainted by admixtures of my own interests – appears to be real.

Some people seem to feel more deeply for others. Watch Sensitive: The Untold Story of Empaths on MagellanTV.

Sympathy, Empathy, and Compassion

Suppose you’re driving down the road when you see an accident happen. Worried that someone you know is hurt, you pull over to see if you can help. (Let’s further suppose you’re not a first responder and there’s nothing to be gained by stopping.) One way of explaining your response is to say you’ve just exhibited sympathy and compassion. To sympathize is to recognize another’s suffering and feel for the person. To be compassionate is to try to help the one suffering.

(Credit: PickPik)

The feeling for or with someone is a shared emotional state. You can, for example, feel for someone who’s just lost their job or just got a new one. That “fellow feeling” that Hobbes allows gets a fuller expression from 18th-century thinkers David Hume and Adam Smith. Sympathy is a psychological foundation of both society and morality. So, rather than take Hobbes’s view that a social contract is the only escape and protection from a brutal world, both Hume and Smith think of the social contract as motivated by moral obligations to further the common good.

Hume and Smith do not share the same theories of morality and social contracts, but insofar as they see both as rooted in human sentiments, their views contrast starkly with Hobbes’s.

We often think of empathy as distinct from both sympathy and compassion. A newer term introduced in the late 19th century by a German thinker was a translation of the Greek empatheia into einfühlung (“in-feeling”). Originally, einfühlung was an aesthetic term. Prior to that, “sympathy” covered both the recognition and mirroring of another’s experience, which often led to compassionate action.

Einfühlung was initially associated with perceptions and experiences of objects. Consider, for example, how we respond to a landscape. The sort of feeling we experience is prompted by the perception, and we effectively imbue the object itself with an expression of that feeling. We might exclaim, “What a beautiful landscape!” and in so doing, project our feelings into the object. The “in” of “in-feeling” meant that one essentially merged with the object.

(Credit: James Wheeler, via Pexels)

Early in the 20th century, “empathy” made its way into experimental psychology, extending beyond the scope of aesthetic meaning to include human beings. Soon enough, thinking about experiencing art and objects in terms of empathy faded, while the social, psychological, and moral dimensions of empathy’s meaning strengthened. At the same time, the wanderings of word meanings often lead to some confusion (or a lack of consensus) within a given field. So, where does this leave the conceptual relation between sympathy and empathy? And what are we talking about when we say that feelings like empathy are crucial to the morality of our social structures?

Sympathy vs. Empathy

A quick look at a dictionary will tell you the contemporary meaning and use of “sympathy” and “empathy.” The two are not synonymous; sympathy means sharing the feelings of another person, while empathy means understanding another’s feelings – with or without feeling the same.

Let’s assume this definition is rigorously correct, though there’s plenty of flexibility and overlap between the two. On the face of it, sympathy looks more … primal, more instinctive, more visceral than empathy. That’s because understanding mediates perception; in a sense, it puts the empathic person at a remove from the object. The sympathetic person’s feeling-with may be closer to a reflexive sort of mimicry, such as feeling the urge to cry when we see someone else crying.

Is Empathy the Evolutionary Source of Morality?

So far as we can tell, many social animals, like herds of horses and prides of lions, don’t exhibit empathy. Nor do many other naturally social creatures. So, from an evolutionary standpoint, what accounts for our ability to understand another’s experience?

If we look closer at our genetic origins, however, we get at least one theory that locates empathy – and so also, according to some, the source of morality – in our non-human primate relatives. In his 2009 book, The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society, primatologist and ethologist Frans de Waal argues that empathy is fundamental to human nature.

Grivet monkey family grooming each other (Credit: Erik Kilby, via Flickr)

Human nature’s roots are in our biological ancestors, which implies that the capacities for both sympathy and empathy are hard-wired into us, not learned. Moreover, though humans, like other animals, can be self-interested to the point of selfishness, we are also, like our non-human primate relatives, social animals.

Aristotle calls human beings zoon politikon, ‘political animals,’ by which he means that we are naturally social creatures whose proper functioning occurs within society.

So, while we can and do compete for resources, territory, and status, we also cooperate and share with each other. That cooperation, according to de Waal, reflects a deep capacity to look beyond, if you will, one’s own self-interest. The caring professions are an example – caregivers, nurses, doctors, and the like.

Consider simple and seemingly automatic ways we sync up with others, like how, when you walk with another person, your footfalls match up, or how one person’s laughter or yawning feels contagious. It’s like that imitation mechanism I mentioned earlier. Sympathy and empathy are thought to originate in these autonomic responses, but certainly humans seem to experience them at a level that leads beyond reactive to cognitive understanding. In other words, we reflect on and theorize about our feelings.

This theory lends itself to the view that empathy is central to morality. After all, we think of morality as including the ability to see another’s actions as ones we ourselves would or wouldn’t take – morality involves particular judgments about ourselves and our actions; we praise and blame, hold responsible, and so forth.

Empathy: Understanding Another’s Point of View

Let’s not worry about the lack of consensus about what differentiates sympathy from empathy – let alone which derives from which, and it may be that there is no derivative relationship. So, instead, let’s think about sympathy in terms of feeling sadness, joy, etc., with another person. Let’s think about empathy in terms of understanding another’s situation, regardless of whether or not we also share their feelings.

A fascinating question related to empathy is what’s required to adopt another’s point of view – that is, to understand another’s situation, feeling, condition, and so forth. To paraphrase 20th century theorist Nel Noddings, when I care about someone – when I am empathetic, sympathetic, and compassionate – I ‘see the other’s reality, the other’s life, as a real possibility for me.’ There’s a sense in which I am at once myself and merged in some way with another.

Recall the former aesthetic use of empathy to describe that feeling of merging with the object? In those moments, “we weave ourselves into the fabric of our worlds.” At the same time, I’m still me. There is good evidence that empathy is what makes it possible to see myself in another. It might be a cognitive capacity, evolved from more primal and instinctive feelings. In recognizing the other’s humanity, we affirm that they are worthy of respect – even if we don’t know or even particularly like them. After all, when I think of myself, I think of a rationally self-interested individual whose interests matter to me. When I empathize with another person, I recognize their interests, as well.

Now, even if I don’t see myself in, say, my dogs, my cat, the local coyotes, and other creatures, I can imagine that they have interests as well. Empathy closes the gap between self and other. Just imagine what that means not only for our daily lives, but also for social and political arrangements and institutions, and for our engagement with other living things and the planet itself.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct instructor at the University of Rhode Island, Community College of Rhode Island, and Providence College. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. She lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.

Title Image credit: Unsplash