Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh is as famous for the circumstances of his missing left ear as he is for his art. Why would he do such a thing?

◊

Vincent van Gogh is renowned for his artwork of intense color contrasts and bold paint strokes, but it is the mystery of his missing ear that has captured the curiosity of many. Though he sold only one painting during his lifetime, his art did gradually gain notoriety over time, as did dark theories about van Gogh’s mental state, his self-mutilation, and the circumstances of his death by a self-inflicted gunshot when he was only 37 years of age.

The events following the moment van Gogh cut off his left ear give few hints of the reasons he committed such a shocking act. As the story goes, in 1888, van Gogh was living in the city of Arles in the South of France. One night in December of that year, he and his friend Paul Gauguin got into a heated argument. Van Gogh threatened his more successful artist friend with a razor, but suddenly turned it on himself and sliced off much of his left ear.

The police discovered van Gogh the following morning in his own bed, showing little sign of life. The wounded artist was brought to a hospital where he was treated. Later, van Gogh’s ear was delivered to the hospital, but it could not be re-attached.

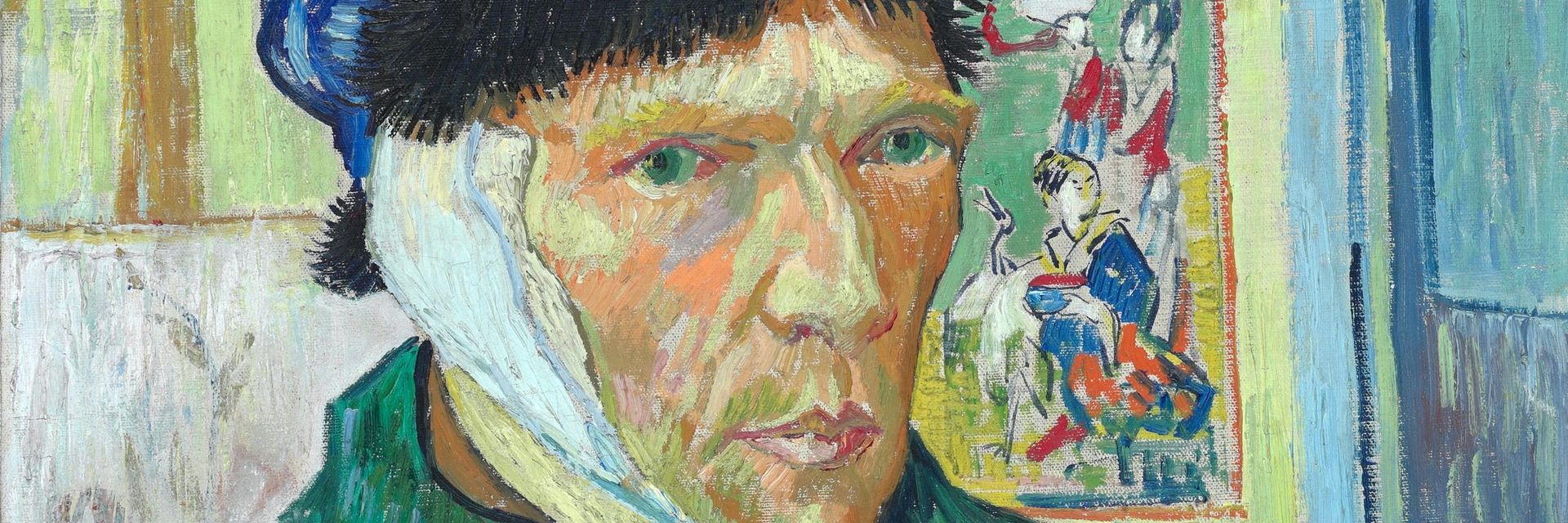

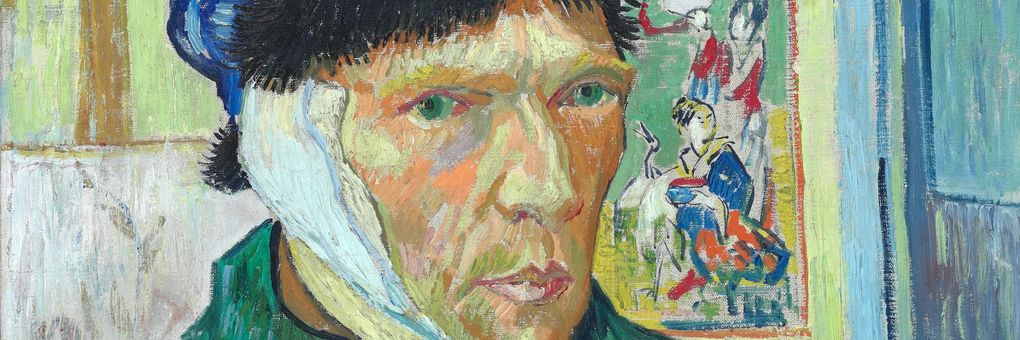

A week after he arrived home from the hospital in January of 1889, believing it would help him to heal, van Gogh painted his now famous work, “Self Portrait With a Bandaged Ear.” The painting, a mirror image, plainly commemorates the loss of van Gogh’s left ear, a large bandage stretching dramatically from his left temple to beneath his chin.

For more on Van Gogh, Gaugin, and their contemporaries, check out the MagellanTV series The Impressionists.

Van Gogh's Impressionist Influences and the Path to Arles

In 1886, Vincent van Gogh, who was Dutch by birth, joined his brother Theo, an art dealer in Paris, and became ensconced in its vibrant art scene. He met many of the leading artists of the time, including Impressionists Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro, and post-impressionists Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Gaugin, with whom he developed a close friendship.

While the Impressionists were noted for the spontaneous and naturalistic rendering of light, Post-Impressionism, with which van Gogh’s art is associated, was centered more around symbolic content, formal order, and structure. Yet, similar to Impressionism, Post-Impressionism highlighted the artificiality of the painting.

For a time, van Gogh thrived in Paris, creating as many as 200 works of art, but eventually the city began to take a toll on his health. In February 1888, he decamped for Arles, on the Mediterranean coast, where he dreamed of starting an art colony.

At first van Gogh struggled to find a place for himself in Arles, though he very much enjoyed the change of scenery. By May of 1888, life was looking up for him. He found an affordable home, an empty yellow house for only 15 francs per month, that he immediately began using as a studio space.

The Yellow House, 1888. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Source: Wikipedia)

From Arles, van Gogh also wrote to his brother about his desire to have artists visit, particularly his friend Paul Gauguin, whom he had met through Theo the previous year in Paris. Vincent van Gogh admired Gauguin and thought him the perfect partner with whom he could start his artist colony. When Gauguin finally joined van Gogh in Arles in October 1888, the two got along well for some weeks, eating, drinking, and painting together. Often, they even painted the same scenes and compared their differing techniques.

Eventually, though, Gauguin began to find it difficult to live with van Gogh, who was temperamental and erratic. For his part, van Gogh often would vacillate between fondness and loathing toward Gauguin. Significantly, the two painters were drifting apart in their painting styles, no longer sharing a common view of art. Gaugin quietly considered parting ways with van Gogh and leaving Arles. Remarkably, it is this turn in their relationship that supposedly lies at the core of the story behind van Gogh’s self-mutilation.

The Painter of Sunflowers: Portrait of Vincent van Gogh, by Paul Gauguin, 1888. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Source: Wikipedia)

But Why Did Van Gogh Cut Off His Ear?

On the fateful evening of December 23, 1888, van Gogh confronted Gauguin, asking if he was planning to leave Arles; Gauguin confirmed that he was. He later explained that on that evening he had decided to sleep in a hotel because of van Gogh’s aggressive, threatening behavior.

Gauguin said that, before mutilating himself, van Gogh had wanted to attack him. He wrote, “I heard behind me a little step that was very familiar, quick and jerky. I turned at the very moment when Vincent rushed at me with an open razor in his hand. My look must at that moment have been very powerful, because he stopped, and lowering his head he ran back in the direction of the house.”

That night, alone in the yellow house, van Gogh used the razor to slice off most of his left ear. Following van Gogh’s mental breakdown and horrible self-mutilation, Gauguin fled Arles and returned to Paris, never to see van Gogh again.

When van Gogh woke up in the hospital, he claimed to remember nothing of the previous night. He insisted that the reason he had cut off his left ear was, “purely a personal matter.” Van Gogh also failed to understand the damage he had done to his friendship with Gauguin, whom he repeatedly asked for. After leaving the hospital, van Gogh would spend the next few weeks between the hospital and the yellow house, as he was tortured by hallucinations and delusions that he had been poisoned.

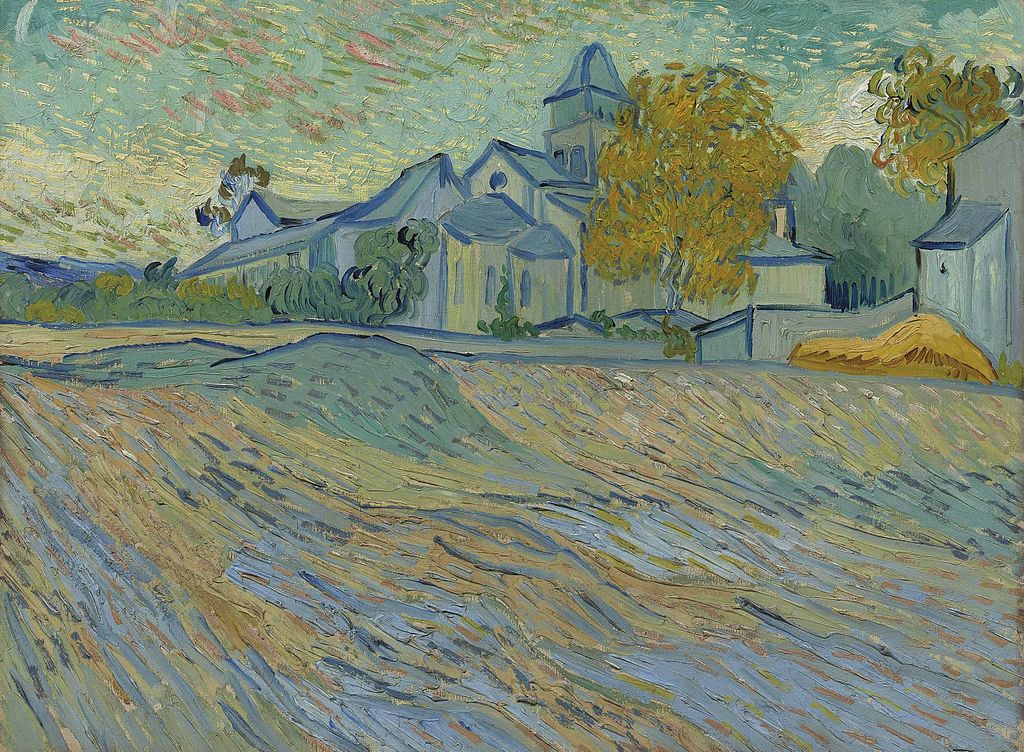

View of the Asylum and Chapel of Saint Rémy, 1889. Private collection. (Source: Wikipedia)

Van Gogh’s Mental Health

On May 8, 1889, Van Gogh arrived at the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence where he would spend the next year. Dr Peyron, who attended to him, determined that van Gogh suffered from a form of epilepsy, accompanied by acute insanity and hallucinations. He made this diagnosis based on the accounts of the doctors in Arles and van Gogh’s own description of his episodes.

In a letter composed when he first arrived at the hospital, van Gogh wrote openly to Theo about his mental state: “Now the shock had been such that it disgusted me even to move, and nothing would have been so agreeable to me as never to wake up again. At present this horror of life is already less pronounced, and the melancholy less acute. But I still have absolutely no will . . .”

Perhaps most heartbreakingly, van Gogh acknowledged that while he first felt afraid of and unlike the other patients, he had begun to see himself in them: ‘‘I observe in others that, like me, they too have heard sounds and strange voices during their crises, that things also appeared to change before their eyes. And that softens the horror that I retained at first of the crisis I had.”

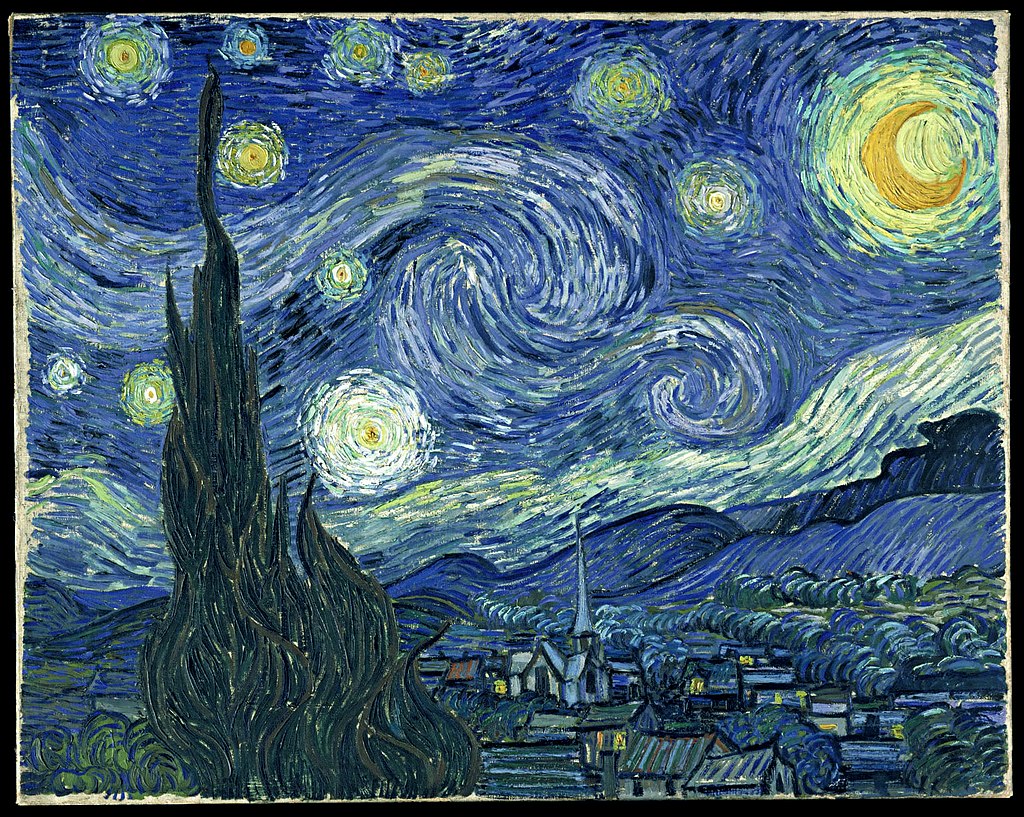

Through the next couple of years van Gogh had periods of recovery and wellness during which he was able to paint, even creating one of his masterpieces, The Starry Night, in June 1889. He also experienced periods of turmoil and psychosis, but he managed to paint well until the end.

The Starry Night, June 1889. Museum of Modern Art, New York (Source: Wikipedia)

Over a century later, in 2016, Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum hosted a private symposium of psychiatrists, psychologists, neurologists, doctors, and art historians to discuss Van Gogh’s possible diagnoses. These experts examined van Gogh’s life and mental health using evidence from his paintings and artwork, writings, and personal documents. Their conclusions could, of course, not provide a definitive conclusion, but instead identified symptoms of various illnesses such as borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, and – slightly less likely – epilepsy.

It is also clear that van Gogh drank too much alcohol, smoked excessively, was often sleep-deprived, and frequently ate poorly, causing all sorts of vitamin deficiencies and impacting his overall wellness. Add to these factors the pressures he was under in his personal and creative life, and a portrait of a man in a profoundly serious crisis emerges.

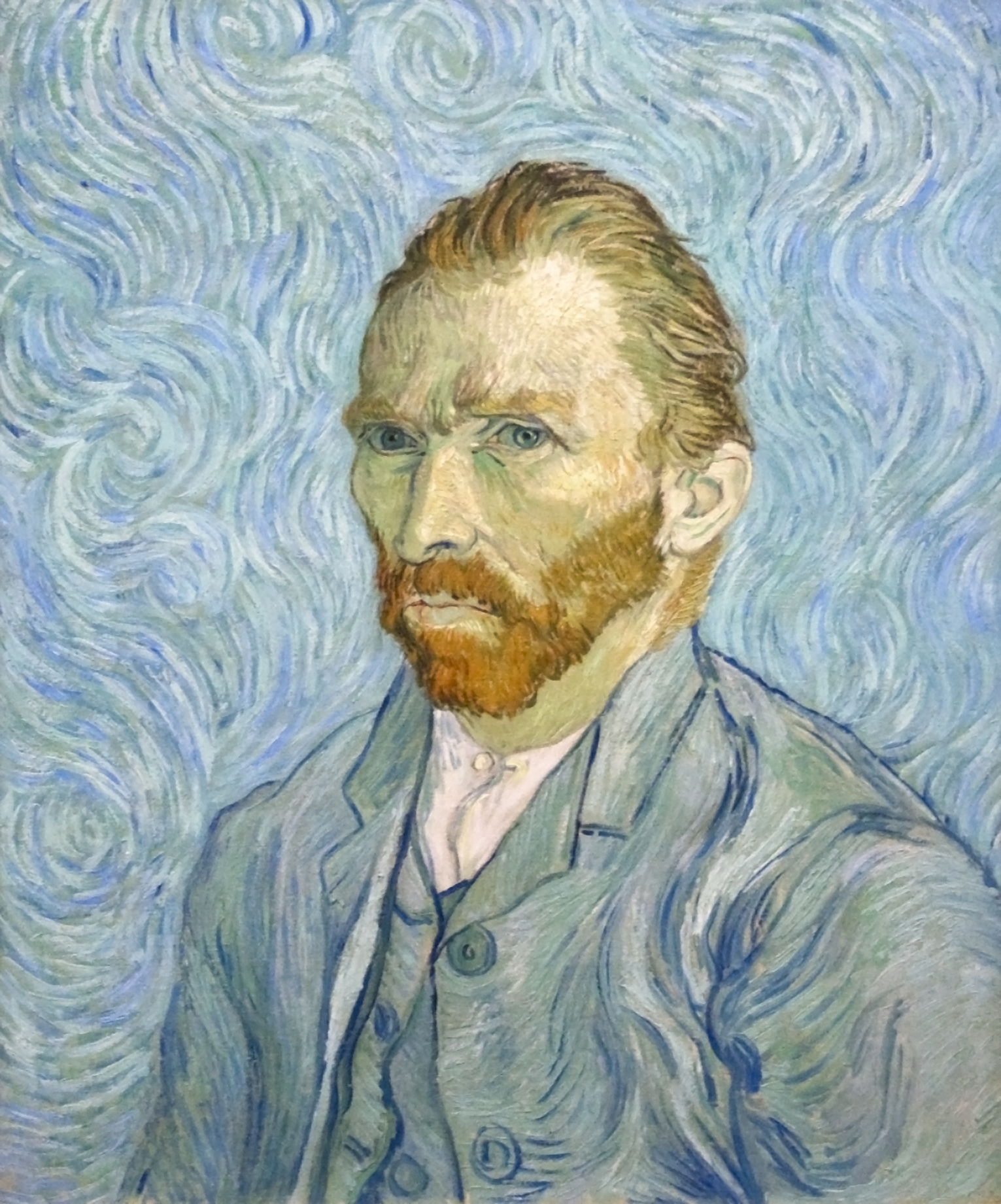

Self-Portrait, 1889, Musée d’Orsay, Paris (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Theories vs. Fact

For the 132 years since Van Gogh’s death, it isn’t only his mental state that has been questioned but also the veracity of the tale behind his self-mutilation. The most popular and well-documented theory is connected to van Gogh’s altercation with Paul Gauguin, but other theories persist.

One such explanation suggests that the confrontation between the two artists was sparked when van Gogh learned of his brother Theo’s engagement to Johanna Bonger, who eventually became the most influential champion of van Gogh’s art after his death.

According to this theory, set forth in Martin Bailey’s 2016 book, Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence, there was likely a December 23, 1888, letter from Theo that disclosed his engagement to Johanna. Such dramatic news might have caused Vincent to feel emotionally threatened, leading him to project his deep emotional insecurity and lash out at Paul Gauguin. However, no such letter has been proven to exist, so Bailey’s explanation appears to be rather weak.

In an even wilder theory postulated by German academics Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans in their book, Van Gogh's Ear: Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence, van Gogh actually made up the whole story to protect his friend Paul Gauguin. Why? Well, according to Kaufmann and Wildegans, Gauguin was a skilled fencer who supposedly sliced off van Gogh’s ear during a heated argument. The historians claim that the truth never surfaced due to a “pact of silence” between the two friends.

One might be inclined to give some credence to one or the other of these alternative theories, but, on balance, the generally accepted tale described in this article – based on van Gogh’s correspondence, newspaper articles, and his doctors’ reports – seems far more plausible.

Want to Learn More About Van Gogh?

More than a century after the gruesome incident, the story behind Vincent van Gogh’s missing ear continues to fascinate. This is partly due to its bizarre and mysterious nature, but it also involves a deeper effort to understand the troubles of a tortured artist and his unappreciated talent. While van Gogh did not garner much attention, admiration, or even affection during his lifetime, today his paintings are among the most recognizable, beloved, and highly valued on the planet, easily certifying him as a peer of the artists he mingled with in Paris and Arles.

To learn more about that fabled world of art and artists, check out MagellanTV’s series The Impressionists.

Ω

Marielle is a contributing writer for Magellan TV. She is a high school English teacher in Queens, New York. She describes herself as creative and a problem solver, and works to build her students into strong critical thinkers themselves. Outside of academia she is passionate about enjoying the outdoors and reading as many books as possible. She lives in Long Island, New York, with her husband and daughter.

Title Image: Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear (detail), 1888. Courtald Gallery, London (Source: Wikimedia Commons)