For the first time, a naval battle was fought in which the principal warships never saw one another. It was also something of a mess.

◊

The five months following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had been one long, brutal series of humiliating losses for the United States and its British, Dutch, and Australian allies. Wake Island, Hong Kong, New Britain, Java, Borneo, Malaya, Singapore, and the Philippines all fell, one after the other. By April 1942, Allied fortunes in the Pacific were at their lowest point. Major warships had been sent to the bottom, entire allied armies had been forced to surrender, and colonial empires had fallen in a matter of days. Things could hardly have been worse.

Japan’s fortunes, on the other hand, had never been higher, with nearly all the credit going to the Kido-butai, the carrier aviation arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). Its pilots were, by all estimates, the world’s best naval aviators, infinitely better trained than their American opponents, with hundreds more flying hours and much of it flown in combat.

The Zero, Japan’s premier fighter, was faster and more agile than what the Americans had. Japan’s Long Lance torpedo was a superb, highly reliable weapon. The American Mk-13 torpedo, by contrast, mostly didn’t work, and the airplane that deployed them, the Douglas TBD-1 Devastator, was underpowered and slow, making it an easy target for antiaircraft gunners.

In the Japanese opinion, American naval aviators, like the aircraft they flew, were inferior. This belief made the Japanese naval commanders arrogant and reckless.

To experience the full sweep of the Pacific war, watch MagellanTV's WWII in the Pacific.

Yamamoto Counsels Caution

The IJN might have been flush with victory and full of optimism, but Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of its Combined Fleet, couldn’t share that attitude. He’d opposed war with America. Having spent years living there, Yamamoto knew full well the unforgiving fury an attack on Pearl Harbor would likely unleash. Tasked with planning it, Yamamoto advised that while he could probably guarantee a string of victories for six months to a year, after that he couldn’t promise anything. By then, he knew, the U.S. would be geared up and out for vengeance.

The admiral’s superiors listened to what he said and told him to do it anyway. For the next five months, Yamamoto delivered victories. By late April, only two tasks remained. The first, which occupied nearly all his attention, was to lure out and ambush the American Pacific Fleet with all its carriers in a grand sea battle near Midway. Yamamoto would run this operation himself.

The other, more-pressing, task, which he was assigning to Vice Admiral Inoue Shigeyoshi, was to take New Guinea and all the islands neighboring Australia. The idea was to gain control of the seas and airspace across the southwest Pacific, cutting off Australia’s sea lines of communication and supply with the Americas. This required taking Port Moresby, with its harbor, docks, airfield and warehouses. Once they had it, they could bring in bombers and start pounding Australia’s northern towns and cities. At the same time, the army would use it as a staging area for the invasion.

The Japanese had already invaded New Guinea from the north side a month earlier, thinking they could take it from behind as they’d done at Singapore. This had been a mistake. They’d seriously underestimated the mountainous jungle between them and Port Moresby. They’d also underestimated the Australians, who proved to be surprisingly tough jungle fighters, especially on the defense. (The Aussie jungle fighters might have been tough, but the half-trained militiamen defending Port Moresby itself were a joke.) The Japanese had been pounding the town with dive bombers for a couple weeks, and whatever the Australians had for defenses were falling apart. All considered, it would be far less problematic just to take it by a direct seaborne assault, which they guessed wouldn’t take more than a couple days.

Japanese bombs exploding in Port Moresby (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

At the same time, they’d begin their seizure of the Solomon Islands chain by sending in a smaller “Light Task Force” to take Tulagi in the eastern Solomons. From there, they’d operate a seaplane base giving them an eye over everything for a thousand miles in every direction. Not being a major operation, the Light Task Force need only consist of the landing force, a single light cruiser, some destroyers, patrol craft, minesweepers, logistics and support vessels, and a seaplane tender.

The Moresby force would be much larger: more cruisers, more destroyers, more everything. There would also be a third group, consisting of the light aircraft carrier, Shoho, and its protective screen of cruisers and destroyers. This group would provide protection to both the Moresby and Tulagi groups from its position between the two. While Shoho would provide air cover as needed to the Moresby invasion, the bulk of that support would come from the land-based 25th Air Fleet, based in Rabaul. Yamamoto believed it should easily neutralize whatever land-based aircraft the Australians and the Americans had based at Port Moresby or on the Australian mainland.

The ‘Mo’ Operation

Yamamoto’s confidence in Shoho’s ability to handle the job was based on his certainty that there were no American carriers anywhere in the region. Earlier, at the beginning of March, there had been two, Lexington and Yorktown, operating off eastern New Guinea and attacking Japanese shipping. But there hadn’t been any sign of either in the six weeks since. The admiral’s guess was both were back at Pearl. This was a good thing, since it meant Yamamoto could keep all his large fleet carriers for the upcoming Midway battle.

All through late April, Shigeyoshi assembled the Port Moresby Task Force from his fleet headquarters at Truk. Officially its name was Mo Sakusen, or the “Mo Operation,” but in all the discussions and radio communications, it was simply, ‘Mo.’

Main maneuvers in the Battle of the Coral Sea, May 1942 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

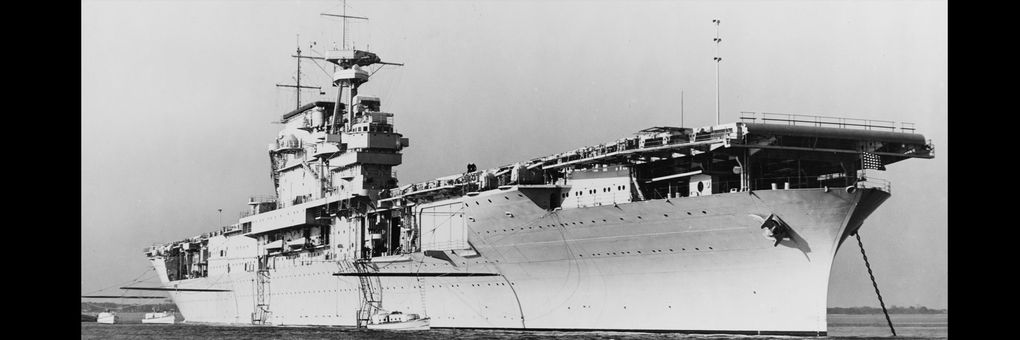

On April 30, 1942, the Port Moresby Attack Force departed the IJN’s large anchorage at Truk, heading south. After rendezvousing with troopships from Rabaul, it entered the Coral Sea, a large area of the southwest Pacific enclosed by eastern New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and 1,200 miles of Australia’s northeast coast. Not long after departure, the force split up into its three elements. The largest would go west toward Port Moresby; the smaller one, east to Tulagi; while the third element, Shoho and its cruiser and destroyer escorts, headed to a location between the other two.

Yamamoto’s certainty that no American aircraft carriers were anywhere in the region flew in the face of repeated warnings from Japanese naval intelligence of the possibility that one might be lurking somewhere. It was enough for Yamamoto that none had been seen in six weeks. He didn’t think carriers were that easy to hide. But the reality was that in the southwest Pacific at that time of year, with all the wind and rain and poor visibility, hiding a carrier was easier than it seemed. With all the bad weather and clouds, navigation was easy to get wrong, and even the best spotters missed things. In the end it was all a matter of calculation and luck. But Yamamoto, always being one for games of chance, was willing to bet there weren’t any.

Nimitz Knew the Aircraft Carrier’s Time Had Come

On May 2, an Australian coast watcher operating near Bougainville reported observing a flotilla of warships, including an aircraft carrier, heading south. This was transmitted to Pearl Harbor and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Reading it, he knew right away it had to be the ‘Mo,’ which his brilliant and highly eccentric head codebreaker, Lieutenant Commander Joe Rochefort, had told him about.

For months, hidden away in a basement at Pearl Harbor, Rochefort’s codebreakers worked to break the Japanese Navy’s operational cipher, which they were calling “JN25D.” The problem was that codebreaking was an imperfect science and JN25D wasn’t completely cracked. Right now, all they knew was something called Mo Sakusen was being prepared, and, judging from the number of times it was showing up in their radio traffic, it was about to go operational. Rochefort, who was also a Japanese linguist, wondered if Mo stood for “Moresby.” If this was the case, then it likely involved an assault on Port Moresby on the southern coast of New Guinea. He had reported his guess to Nimitz, who thought it made sense and immediately acted on it.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (Portrait by Dean Cornwell. Source: National Portrait Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons)

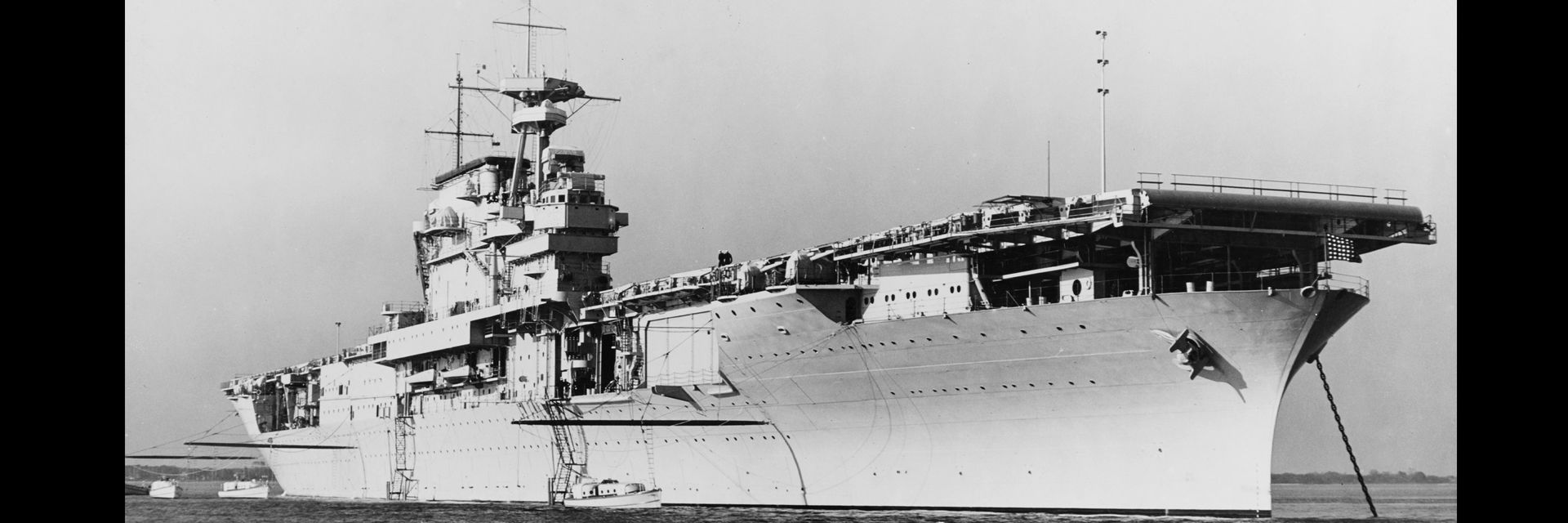

Normally, in situations where they knew the enemy’s intentions but not their strength, Nimitz’s solution was to send battleships and all the carriers he could muster. But his battleships had all been sunk and of the five carriers under his command, Saratoga was undergoing major repairs in Bremerton, and Lexington was at Pearl Harbor getting a quick refit, while Enterprise and Hornet hadn’t yet returned from the Doolittle raid on Tokyo. Only one of his carriers, the Yorktown, was available, and, as luck would have it, it was just then keeping a very low profile in the Tonga islands, east of the Coral Sea.

Nimitz cut short Lexington’s refit, ordering it and the other ships in the task force to make all preparations for immediately getting underway. He had already replaced its commanding admiral, Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, who, while capable, was old, sickly, and not an aviator, with Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch, who was. Fitch was instructed to head south to the Coral Sea and rendezvous with Yorktown and then go against the Japanese fleet with everything they had. Port Moresby and Australia must not fall!

Nimitz guessed the ensuing battle would be a brawl between carriers. He worried that his leading task force commander, Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, a “black shoe” whose career had been aboard battleships and cruisers, was hobbled by those black shoe institutional prejudices. He might lack the imagination and not fully grasp the radically different dynamic situations this new kind of naval warfare was going to present.

But Fitch would. He was a “brown shoe,” an aviator. Fitch’s career was focused on the questions and possibilities which Nimitz guessed would play out during this battle. Nimitz and Fitch, like their Japanese counterparts, Yamamoto and Shigeyoshi, knew the day had arrived where sea battles were fought not with battlewagons and cruisers but with carriers, completely out of sight of each other. The surface combatants wouldn’t fight it out with each other. They’d be there primarily to protect the carriers.

Surprise Appearance of Yorktown at Tulagi

On May 3, the Japanese Light Task Force reached Tulagi. Its assault force landed and found it had been abandoned by the Australians several days earlier. Almost immediately, work crews came ashore with heavy equipment and soon construction on the planned seaplane base was underway.

Meanwhile, as Fitch’s Task Force 11 raced down from Hawaii, Fletcher’s Task Force 17 entered the Coral Sea from the east, its scout aircraft already out combing the cloudy seas below in search of the Japanese fleet. High over Tulagi, one of Yorktown’s aircraft, spotted the Japanese ships and thought they included some cruisers.When the news reached Fletcher, it was already late afternoon.

The next morning, Fletcher sent out a large number of Douglas Dauntless dive bombers and Devastator torpedo planes to attack Tulagi. To Fletcher’s delight they reported sinking at least one cruiser and several destroyers. But they had, in fact, done very little real damage. A destroyer had been sunk, and a minesweeper was hit with numerous torpedoes, almost sinking it, but not quite. The attack was over in a couple minutes. Construction of the seaplane base continued. Weeks would pass before they saw any more American carrier aircraft.

Dauntless dive bombers (Source: U.S. National Museum of Naval Aviation, via Wikimedia Commons)

When word of the American attack reached Yamamoto, he realized he’d let himself get fooled. An American carrier had indeed been in the area the whole time, hiding. With that, a whole new calculus presented itself. Shigeyoshi needed carriers, otherwise the Moresby task force was in danger! Much as he hated the idea, Yamamoto knew he had to tap into the force of carriers he had set aside for Midway.

He told Shigeyoshi he was sending down Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi’s Carrier Division Five with its two large fleet carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku. But it was just a loan, for just a couple of days, until they had Port Moresby secured. After that, the carriers would go back to Truk. It was imperative that Yamamoto have numerical superiority when he went up against the Americans, who he was sure would come after him with everything they had once his force attacked the U.S. base at Midway.

‘Scratch One Flattop’! – The Action as It Happened

Following the Tulagi attack, Fletcher takes his ships south for refueling. While this is happening, aircraft from the Japanese 25th Air Fleet begin a new round of strafing and bombing attacks on Port Moresby in advance of the planned invasion. Also at around this time, on May 6, coast watchers spot Takagi’s carrier task force rounding the tip of the Solomons as it enters the Coral Sea.

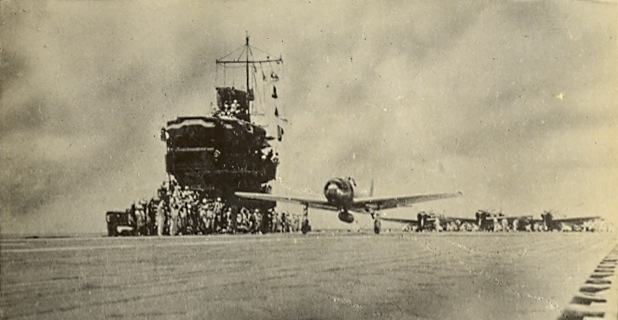

When news of the carriers reaches Fletcher, he incorrectly assumes they are coming east to protect the Tulagi flank. Hoping to get the jump on them, Fletcher orders his task force to head west-northwest. But Takagi’s force is actually heading west to join the Moresby invasion fleet. Fletcher and Fitch link up their task force, which also gets joined by two Australian cruisers, the heavy cruiser Australia and the light cruiser Hobart. Fletcher expects it will take another day to reach the Japanese force. But Admiral Takagi’s carrier force is closer than he thinks.

Heavy cruiser HMAS Australia (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

At dawn the next day, May 7, Fletcher sends out aircraft in search of the Japanese. Although the weather is bad and visibility poor due to so many low-lying clouds, one of Fletcher’s search planes spots some ships near the Deboyne Islands in the Louisiade Archipelago and reports the sighting. At 0930, Fletcher launches a strike force of 50 aircraft from Lexington and 43 from Yorktown in the direction of where he believes the Japanese are heading. At the same time he orders Admiral John Crace, commander of the Australians, to take his two cruisers west to the Jomard Passage and to wait and block the Japanese invasion fleet on its way to Port Moresby.

Takagi also launches his scouting planes. At this point, the assumption is that there is only one American carrier in the area. In fact, there are two. At 0722, Takagi receives a radio message from one aircraft reporting a target in the southwest that seems to consist of a single American carrier escorted by a cruiser and a number of destroyers. Takagi immediately sends a large force of fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo planes to take it out.

As the Japanese aircraft head toward what they believed is an American carrier and cruiser, the American aircraft sent out by Fletcher reach the Deboyne Islands. But, instead of finding the two large fleet carriers, the Americans find only the light carrier Shoho and its escorts, which had withdrawn there to lay low following the American attack on Tulagi. Shoho only has five planes up on Combat Air Patrol when the Americans attack. It also turns out the Shoho’s four escorting cruisers are not effectively positioned around it to provide protection. The American aircraft make short work of Shoho, sending it to the bottom in only 25 minutes.

Artist’s depiction of the sinking of Japanese light carrier Shoho (Credit: Robert Benney, via U.S. Naval Institute)

In elation, the attackers telegraph back to Fletcher: “SCRATCH ONE FLATTOP.” For the Japanese, it’s not just the first carrier they are to lose in the war, but also the first major warship. It will not be their last. When Shigeyoshi learns of Shoho’s sinking, he decides his Port Moresby assault ships are too vulnerable to Allied air attack and orders them to turn around and withdraw to Truk.

The Japanese Attack a Tanker, Not a Carrier

Around the same time, Takagi’s strike force reaches its target, only to discover it isn’t an aircraft carrier with cruiser escorts but rather a fleet oiler, Neosho, and its single destroyer, Sims. The Japanese attack, sinking Sims with a single bomb. Neosho, although badly hit by bombs and torpedoes, remains afloat, thanks to the efforts of her damage control crews.

The USS Neosho was named after a river in Kansas and Oklahoma. A crewman, Oscar V. Peterson, was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the attack.

By now it is late afternoon. Takagi is furious that he’d sent so many of his aircraft out against what would turn out to be a secondary target. He orders out more scouting aircraft, even though he is well aware that recovering aircraft at night, even under the best conditions, was a risky practice. Although the seas are unruly, Takagi feels it is a risk he must take.

Meanwhile, Crace’s two Australian cruisers, having reached the Jomard Passage, wait for the Japanese invasion fleet, not knowing it is already in retreat. Japanese scout planes spot the cruisers. Not long after, the ships are attacked by Japanese bombers and torpedo planes. Because Hobart is hidden by clouds, the Japanese focus on Crace’s flagship, Australia, which, thanks to its captain’s expert handling, manages to avoid being hit.

But just before the Japanese depart, the fracas is observed, from a distance, by patrolling land-based American aircraft, who assume the departing planes are also American and that the warships are therefore Japanese. So the Americans now take over the attack on the Australian ships, and again, through luck and deft handling, the Australians avoid getting hit. Afterwards, both the American and Japanese aircraft return to bases and carriers and report sinking major enemy ships.

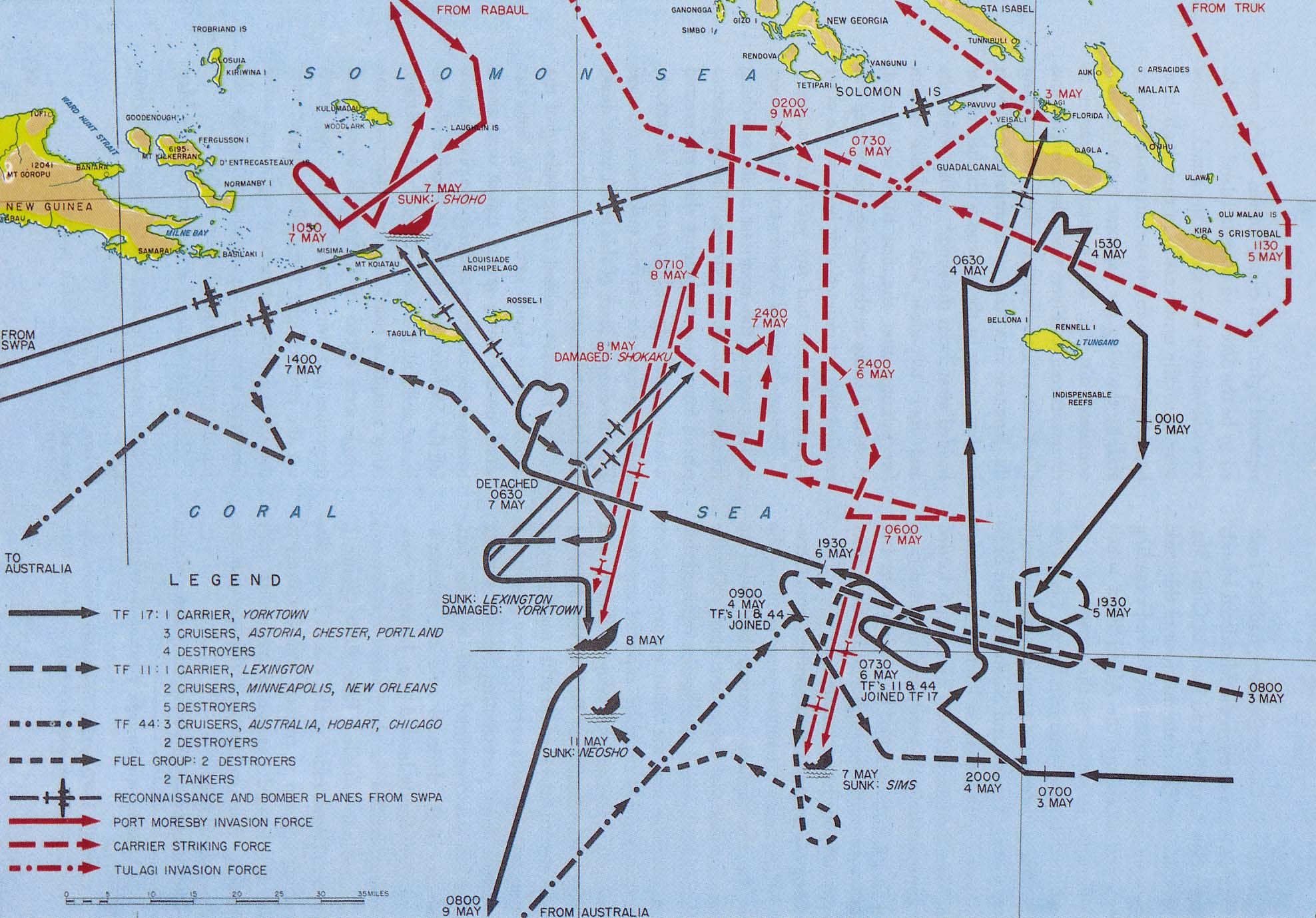

Japanese Zero fighter taking off from aircraft carrier during the Battle of the Coral Sea (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Through the late afternoon on May 7, Japanese aircraft continue searching for the American carriers. As darkness approaches, Takagi makes a critical mistake by not recalling them; it is after dark when most return. Some crash into the sea, others onto the darkened flight deck. One airplane, hopelessly lost, attempts landing on a carrier which turns out to be American. Of the 27 Japanese aircraft that Takagi had sent armed with bombs and torpedoes, only 18 make it back whole.

All at the Same Time

At daybreak on May 8, both sides try again. Unbeknownst to each other, they are only 217 miles (350 kilometers) apart. Both send out reconnaissance aircraft to find the other, and, at about the same time, they do. Both sides then launch their aircraft against the other – without either side knowing the other’s location.

As the massed fleets of aircraft fly toward the other’s carriers, they pass each other, at a distance, but close enough for some to see the others. At one point, the Japanese scout aircraft that had located the American carriers actually encounters his comrades in the attacking force. Unsure of the accuracy of the coordinates he’d given, he turns his airplane around and leads them there, knowing he won’t have enough fuel to get back. After guiding them to the American carriers, his fuel gone, he crashes his plane into the sea.

Just before 1100, Lexington’s radar spots the approaching enemy aircraft. Immediately, Lexington and Yorktown begin launching their remaining defensive fighters. At roughly the same time, the Japanese and American air fleets reach their targets. All hell breaks loose. The Japanese focus most of their attention on Lexington. She is struck by two torpedoes on her port side; one forward, the other amidships. She is also hit by several 1,000-pound bombs on her island and flight deck. Yorktown, while managing to avoid torpedoes, is hit by bombs, which cause severe damage.

As the Japanese strike on the U.S. carriers is underway, the American aircraft attack Shokaku. The Douglas SBD Vindicators come in low and slow and release their torpedoes. Some get shot down, and the torpedoes of others hit their targets – but none explode or do any damage. Bombs dropped by the Dauntless dive bombers do, however, score a number of hits. One aircraft goes into its deep dive, but instead of pulling up following the bomb’s release, continues down, crashing into the sea as its bomb hits the ship and explodes. Zuikaku, seven-and-a-half miles (12 kilometers) away and hidden in clouds, never gets attacked.

When the attack ends and the American aircraft depart, Shokaku is so severely damaged, it cannot land any of its returning aircraft. Instead they land on the Zuikaku, which doesn’t have room for them all. As a result, many get pushed off into the sea to make room for those needing to land. In the end, the Japanese lose 45 of the 72 operational aircraft they’d started with the day before.

Lexington, with two large holes at her waterline, takes on water and develops a seven degree list. It is corrected by counterflooding and flight operations continue. However the ship’s damage is worse than originally believed. Ruptured fuel lines leak aviation fuel into some of the ships internal spaces, filling them with highly combustible fumes. At 1247, an explosion rocks the bowels of the ship, and fire spreads throughout Lexington’s lower decks.

USS Lexington burning on May 8, 1942 (Credit: National Museum of the U.S. Navy, via Wikimedia Commons)

Despite this, returning aircraft continue landing on its decks, though smoke can be seen coming through the flight deck. By the time the last aircraft are recovered, the fires are out of control. The order comes to abandon ship. Even so, Lexington somehow remains afloat. After the last of the surviving crew were taken out of the water, one of its escorting destroyers fires a torpedo at Lexington, sinking her.

After that, Fletcher orders his ships south. Neosho, discovered still afloat four days after being torpedoed, has its crew taken off. A torpedo is put into her, and she finally sinks. Takagi’s fleet turns north, out of the Coral Sea and back to Truk.

Tactical Defeat or Strategic Victory?

Technically, the Japanese had won. The Americans had lost one of its fleet carriers, a destroyer, and an oiler. Japan had only lost a light carrier, a destroyer, and some smaller vessels. The Americans lost 66 aircraft, while Japan lost 77, though the loss of aircrews was smaller. The telling difference would be their replacements.

As good as the American pilots were, none were previously veterans, as were the Japanese. The U.S. Navy’s pilot training program was already in the process of massive growth and the lost pilots would quickly be replaced by hundreds more who were “good enough” to throw into aerial combat. With the Japanese, it would be different. Kido butai’s naval aviators, trained to a much higher standard, were not so easily replaced. Perfectionists, they would not expand training, as the Americans did, or compromise their sense of excellence. In time it would contribute to their defeat.

While both Shokaku and Zuikaku would fight another day, neither saw action at Midway a month later. Their absence would contribute, critically, to Yamamoto’s defeat in what would prove to be one of the most pivotal battles of the Second World War. Yorktown managed to limp back to Pearl Harbor on its own power. There, she underwent massive repairs, and within a matter of days, went back out one last time. Though she would ultimately be sunk at Midway, she played a decisive part in winning that battle.

In the end, the Battle of the Coral Sea might have been a tactical victory for Japan, but it was a strategic victory for the Allies. The planned assault on Port Moresby was turned back. While the Japanese did manage a number of air raids on Darwin and other towns on the Australian mainland, that was as far as it went. Japan’s expansion was blunted at Coral Sea, but became a retreat a month later at Midway.

Ω

Brendan McNally is an author and journalist focusing on military history and espionage. After covering the Pentagon, he relocated to Prague and spent the 1990s covering the arms trade. He now lives outside Albany, New York. He’s written two novels, one, Germania, set during the brief “Flensburg Reich” of Hitler’s successor, Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz; and Friend of the Devil, about God, the Devil, and Mexican “border blaster” radio stations in the 1930s. His non-fiction book, Traitor’s Odyssey, forthcoming this fall, is about Soviet spy and party girl Martha Dodd.

Title Image: USS Yorktown anchored at Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1937 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)